Director Joaquin Oristrell’s film Mediterranean Food (Dieta Mediterranea) follows in a long line of distinguished food movies. Like many of these movies, it is not really about food at all. Perhaps food is too essential a topic to be easily isolated, inevitably extending its range to all the realms of our senses and passions. One thinks with fondness of how food is used as an allegory, a metaphor, a code and a symbol for all that is most fundamental to us in films like Babette’s Feast (1987) or Eat, Drink, Man, Woman (1994), Delicatessen (1991) and Tampopo (1987). Whatever else they are about, they never forget the simple thing about food: that it is something we eat. At the other extreme, the food movie has also been callously misused as nothing more than a sexy backdrop to celebrity posturing in utterly superficial concoctions such as Catherine Zeta-Jones’ No Reservation (2007) and Penelope Cruz’s Woman on Top (2000).

Mediterranean Food falls somewhere between those two extremes. It tells the story of Sofia (Olivia Molina) from her childhood at a small seaside cantina to becoming a famous chef, a journey she accomplishes not just through her passion for food, but also through her passion for the two men in her life: the steady Toni (Paco Leon) and the venturesome Frank (Alfonso Bassave). They both appeal to different aspects of her personality and her ambition, and she is not really prepared to give up either of them. It helps that one is good with accounts, the other a talented maitre d’hotel.

It is a situation not without comic potential, but Oristrell seems content to take the easy path and turns Mediterranean Food into a story about how Sophia manages to get her cake and eat it too, as she successfully talks the two men into a menage a trois that has the local community up in arms.

Molina gives a spirited performance as Sophia, the girl who wants to make it in the male-dominated world of the restaurant kitchen, but her two male admirers let her down badly, with Paco Leon’s Toni never getting much beyond the comic innocent; though this is somewhat preferable to Alfonso Bassave channeling early Antonio Banderas.

The film gets off to a promising start, and there is an interesting idea that lurks in the background about seemingly incompatible combinations (whether of ingredients or people) turning out to be marriages made in heaven if approached with the right kind of zest for life and all its riches. Sadly, the development of this, or any other theme, rapidly takes a back seat to sex, and the director goes for some easy gags about three-ways and a swelling homoerotic relationship between the two men. The film wants to be bold and sexually daring, but it fritters away any real tension, satisfied to generate some tittering laughter with its sexual high jinks.

Occasionally the film throws up interesting observations about food and the ways it can become part of our lives, but the director does not really know what to do with them, and lets them flop back down with a disappointing thump. The bedroom rather than the kitchen is at the center of the movie, and it doesn’t help that the filmmakers seem to confuse Japanese kaiseki cuisine with the techniques of molecular gastronomy.

Good food movies are all about attention to detail, and the food in this film is never given the same kind of close attention that is lavished on Bassave’s admittedly rather fine buttocks. Oristrell, who did well at the Barcelona Film Festival and picked up a Sundance nomination for Unconscious (2004), a humorous take on the world of psychoanalysis, clearly has intellectual pretensions. They are evident in Mediterranean Food, but here remain nothing more than pretensions as he gets sidetracked into a lightweight romantic comedy that makes up for the lack of jokes with a smattering of risque situations.

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

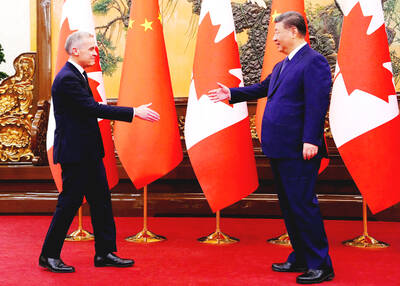

Britain’s Keir Starmer is the latest Western leader to thaw trade ties with China in a shift analysts say is driven by US tariff pressure and unease over US President Donald Trump’s volatile policy playbook. The prime minister’s Beijing visit this week to promote “pragmatic” co-operation comes on the heels of advances from the leaders of Canada, Ireland, France and Finland. Most were making the trip for the first time in years to refresh their partnership with the world’s second-largest economy. “There is a veritable race among European heads of government to meet with (Chinese leader) Xi Jinping (習近平),” said Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, director