At one time, airline safety generally meant one thing: avoiding a crash. But safety regulators are increasingly focusing on surviving one.

Starting this fall in the US, all new airplanes will be required to have seats that will stay in place when subjected to stresses up to 16 times the force of gravity. The old seats had to meet stresses of only nine times the force of gravity. And, in a safety measure borrowed from automobiles, some seats will be equipped with air bags.

The combination of sturdy seats and air bags means that if a plane touches down short of the runway or rolls off the end of the runway and hits an obstruction, “You’re going to be conscious. You’re going to have the opportunity to survive,” said Bill Hagan, president of AmSafe, which makes the air bags.

In some airline crashes, the strength of the seats is irrelevant because the crash is not what the engineers call “survivable.” In other crashes, still violent but not as much so as exploding in midair or breaking up in flight, the passengers’ survival depends on suffering little or no injury in the first phase of the accident, as when a plane runs off the runway, and then getting out of the plane quickly to avoid a post-crash fire.

The new rules have taken effect gradually. Airplane models introduced after 1988 were required to have the new seats, known as “16g” seats. So planes like the Boeing 777 and the swarm of new regional jets all have them. But older models that were still in production were not required to have the seats.

But beginning Oct. 27, new airplanes of models certified before 1988 must also comply. In practice, aircraft manufacturers have been delivering many planes that meet the new rule for some time. So the deadline is more of a milestone than an actual change-over date.

But while Boeing has been delivering 737s for years with the 16g seats, the 747-400 — the current model of the 747 — still had the old 9g seats. But Boeing produced its last 747-400 a few weeks ago. A new model, the 747-8, will be introduced soon with the sturdier seats. Sandra Angers, a Boeing spokeswoman, said that few planes had been delivered lately with the old-style seats because few designs from before 1988 were still being manufactured.

PASSENGERS CAN SURVIVE

The new rules do not affect older planes with the old seats. But those planes are disappearing from airline service because they are less fuel-efficient than newer models and because the total number of planes is down as airlines cut service in the recession.

Safety regulators decided to impose the new rules after they found that passengers might survive a crash were they not crushed to death when the seats tore loose from the floor. The 16g standard was chosen because a deceleration more severe than that is not survivable. A stress of 16 times the force of gravity is equivalent to a velocity change of 48kph almost instantaneously.

In four recent accidents involving big jets, everyone on board walked away. One of those happened in August 2005 when an Air France Airbus A340 slid off the end of a runway on landing in Toronto. All 309 on board got out before the plane was consumed by fire. In other cases, the seats make no difference, as in the Air France crash in the Atlantic on June 1.

In contrast, an investigation by British authorities into the crash of a Boeing 737 in the Midlands in January 1989 showed that some passengers died of crush injuries when the floor broke up and the seats came loose. Stronger seats might have increased the number of survivors and reduced the severity of injuries, the report suggested. Forty-seven passengers died and 74 of the other 79 on board were seriously injured.

Airplane seats are tested using some of the same methods highway safety authorities use on car seats. The plane seats are tested on sleds, using

crash-test dummies borrowed from automobile testing. There are a variety of test criteria, including one for head trauma that is the same as that used by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

BORROWING FROM AUTOMOBILES

The changes to the seats themselves, and the floor structure that supports them, will not be obvious to passengers. But the air bags are visible. They are built into one side of the lap belt, which appears a little thicker.

The air bags also borrow technology from automobiles. They are set off by a shock meter that comes directly from cars. And like the systems used in cars and trucks, the seat belt air bags in planes are designed not to deploy inappropriately — in cases of air turbulence, for example.

In fact, said Hagan, this is simple, because the air bag sensor system watches for shocks on the axis on which the plane is traveling; it does not monitor up-and-down or side-to-side movements of the kind produced by turbulence, he said.

The air bags are widely used in first or business-class cabins, where the seat in front is too far away or angled in such a way that it cannot function as a cushion. In coach class, the air bag has started out for use in front rows, exit rows and bulkhead seats, near galleys or toilets. In other seats, the passenger gets some protection from the seat back directly ahead, which is designed to break in a controlled fashion, providing a cushion.

Singapore Airlines flies 777s with wide intervals between seats and uses the air bag, Hagan said. JAL, Cathay Pacific and Virgin also use them, he said.

When Taiwan was battered by storms this summer, the only crumb of comfort I could take was knowing that some advice I’d drafted several weeks earlier had been correct. Regarding the Southern Cross-Island Highway (南橫公路), a spectacular high-elevation route connecting Taiwan’s southwest with the country’s southeast, I’d written: “The precarious existence of this road cannot be overstated; those hoping to drive or ride all the way across should have a backup plan.” As this article was going to press, the middle section of the highway, between Meishankou (梅山口) in Kaohsiung and Siangyang (向陽) in Taitung County, was still closed to outsiders

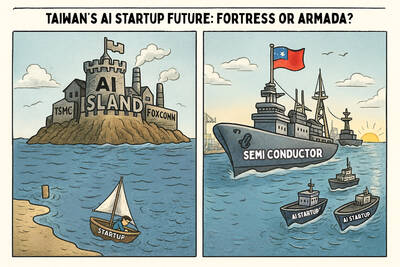

President William Lai (賴清德) has championed Taiwan as an “AI Island” — an artificial intelligence (AI) hub powering the global tech economy. But without major shifts in talent, funding and strategic direction, this vision risks becoming a static fortress: indispensable, yet immobile and vulnerable. It’s time to reframe Taiwan’s ambition. Time to move from a resource-rich AI island to an AI Armada. Why change metaphors? Because choosing the right metaphor shapes both understanding and strategy. The “AI Island” frames our national ambition as a static fortress that, while valuable, is still vulnerable and reactive. Shifting our metaphor to an “AI Armada”

The older you get, and the more obsessed with your health, the more it feels as if life comes down to numbers: how many more years you can expect; your lean body mass; your percentage of visceral fat; how dense your bones are; how many kilos you can squat; how long you can deadhang; how often you still do it; your levels of LDL and HDL cholesterol; your resting heart rate; your overnight blood oxygen level; how quickly you can run; how many steps you do in a day; how many hours you sleep; how fast you are shrinking; how

US President Donald Trump may have hoped for an impromptu talk with his old friend Kim Jong-un during a recent trip to Asia, but analysts say the increasingly emboldened North Korean despot had few good reasons to join the photo-op. Trump sent repeated overtures to Kim during his barnstorming tour of Asia, saying he was “100 percent” open to a meeting and even bucking decades of US policy by conceding that North Korea was “sort of a nuclear power.” But Pyongyang kept mum on the invitation, instead firing off missiles and sending its foreign minister to Russia and Belarus, with whom it