VIEW THIS PAGE “I lie all the time,” says Ricky Gervais. “The last lie I told was the last time someone invited me to a wedding, or a christening, or a party. I can’t say, ‘I don’t really like you that much, I’m worried about the other people you’d invite; a wedding bores me stupid, I think it’s ridiculous and pointless and I’d rather sit at home in my pants drinking wine.’”

So what does he say?

“‘When is it? Oh, I can’t do Saturday.’ But they’re white lies. There wouldn’t be any point in telling the truth.”

Gervais is getting frank about fibbing because his latest character — a misanthropic British dentist called Bertram Pincus, whom he plays in his new movie, Ghost Town — can’t manage a tactful lie. Pincus, like Larry David in Curb Your Enthusiasm, is a fantasy figure for those frustrated by the need to stick to good manners.

“He thinks he’s got special rights to be honest,” Gervais says, “when actually it doesn’t get you anywhere and it hurts people. Old women have the right to say what’s on their mind. My mum had rights. ‘Oh Rick,’ she used to say. ‘You’re going to get followed; you look like a right poof.’”

Looking at Gervais is unnerving, though not for the same reasons his mother was unnerved: your brain keeps tripping you up, insisting that you are, in fact, watching TV. Listening, too. The voice is David Brent, all the time: the accent, the attitudinal punctuation. Later on he says, in one go: “It doesn’t annoy me that other people believe in God, but indoctrination annoys me a bit, and obviously religious fascism; it’s the only thing that makes my blood boil, that and animal cruelty. The threat of violence because someone disses your God that I know doesn’t exist.”

All serious points, but run together like that they somehow make you feel like giggling. It’s the big words in the flat tone, and the stress on “I know”; the “along with animal cruelty.” It goes into your head and gets muddled up with Brent saying of Dolly Parton: “And people say she’s just a big pair of tits.”

Otherwise, though, just to be clear: Gervais is absolutely nothing like Brent. Nor Andy Millman from his hit BBC comedy Extras. Nor Pincus. All three are horrifically honest misfits who spend so much time with their feet in their mouths that only someone hypersensitive to social niceties could create them.

The seeds were sewn by a magician friend years back. “A friend used to do this card trick where, for about 10 seconds, you thought he’d really messed up, before all was revealed to be part of the act,” he says. “I grew to love that 10 seconds, of people feeling sorry for him, of feeling a bit smug. And I’ve always tried to do that. People thinking: this is terrible, this is awful, this is uncomfortable.”

Pincus is, in some ways, a step on from the psyches of Brent and Millman: he’s happy with himself, for a start. He’s bright, and witty, on occasion.

“I met a lot of people — well, men — at university who were like that,” says Gervais (he studied biology at University College London). “Higher logic, lower emotion. They came across as rude, but they didn’t mean it. It was as if they had some sort of barrier in their social intercourse.”

For Pincus, this barrier is broken after he goes into hospital for a colonoscopy, briefly expires on the operating table, then wakes to find that he can see dead people, all of whom want his help. Greg Kinnear’s ghost wants him to stop his widow, Tea Leoni, marrying the wrong man. You can guess what happens. The surprise is how skillfully it’s handled. This is a terrifically funny and moving film, with a weirdly dignified central performance.

Gervais is proud of it (“classy” seems to be his adjective of choice). No wonder: where other, more superficially plausible homegrown comedy stars have tried and failed to crack the US, Gervais has succeeded in spectacular fashion. Partly it is because he saved himself for the right script, rather than succumbing to “some terrible British film about trying to get a hockey team into division two.” And partly it’s because there’s so much heft and feeling — indeed, such a prioritization of feeling over action that there isn’t a single snog in the film. Also, this is turf that Gervais knows: the desperate difficulty of understanding one another, the social comedy in endless tiny glances.

“It’s about a man whose life gets turned around by an external force — it’s a high-concept movie; there’s ghosts in it — and so he starts realizing that he’s missing out on the most important thing in life, which is contact with people.” You could read Pincus’ transformation as a sort of limey rehabilitation: is he having his British emotional ineptitude purged, learning how to become — whisper it — American? Did Gervais recognize that as Pincus’ path to redemption?

“Redemption,” he says, little eyes gleaming, “is my favorite thing. As an atheist, I think forgiveness is the greatest virtue. You have to be a very harsh person to not accept someone genuinely saying sorry. That’s why at the end of Extras we did it plainly and cleanly when he just looked down the lens and said to Maggie: ‘I’m so sorry.’ I think it’s much stronger than forced poetry.”

Redemption seems to be a watchword for Gervais. The reason it’s so crucial, he thinks, is that it helps the viewer feel involved in the script. “In every good comedy or drama someone represents us. If they’re redeemed, we feel we’ve been liberated, or saved. If it’s done well, you’re part of the journey. That’s why everything begins or ends with empathy. If you’ve got that, you’ve got nearly anything. Everything else is the icing on the cake.”

Because humans are basically self-interested? “Yes. I don’t think there’s any real altruism. But you want to be in a society where everyone’s all right, otherwise it’s not OK for you.”

Because you feel guilty?

“Because it’s not a good place to be. Deep down, we’d like everyone to be happy, because then you’re happy.”

What really seems to hook his interest here is the science of a successful script. Fellow-feeling is just how your brain works, and understanding that is important because Gervais wants to harness it for dramatic ends. “Laughing is infectious. Crying makes you feel a bit sad,” he says. “We’re hard-wired. So if you get empathy on screen, it hits you on an emotional and subliminal and fundamental level.”

He warms to his theme. “Someone can do a hundred of the best one-liners. You’d laugh. But they could throw in a false punch line and you’d still laugh because you’ve got the rhythm. You won’t remember one of them, and you won’t care. But with Laurel and Hardy, say, I like them because I want to hug them. I laugh because I fucking love them. I can’t laugh at someone I don’t like. If someone’s hurt you it’s not funny. It’s not that you stop yourself laughing; it’s just not funny.”

Fail to appreciate that, he thinks, and your comedy can’t resonate with the audience. “After The Office, there was a rush to play unsympathetic characters. But with a lot of them, there was no redemption and no worthwhile journey. You need representation, not just embarrassment. The Office would never have worked had Tim not existed. You need someone to roll your eyes with. You can’t just have decapitated jokes. Then what you’ve got is a sketch show.”

It’s strange to hear Gervais explain his puppet mastery. He seems to split his audience into two: his peers, and the rest of us, who’ll laugh at anything, who’d even lap up the likes of When the Whistle Blows (the terrible fictional sitcom that transforms Millman from one of the Extras to being a star). He’s stealth-feeding us quality while we’re distracted by trash and color. “I like doing things that are Trojan horses,” he says. “You start people watching with the knockabout stuff but then you take them to a different place. I know fully that with The Office, people tuned in for Brent and kept watching for Tim and Dawn.”

Does he really think we need nourishment smuggled into our diets? “Of course. Otherwise it’s empty. It’s just white bread. And it’s a matter of bothering to make it good. You’re going to be there anyway. People make bad television and get promoted just because they made television. Aim high — then, if you fail, you’re still slightly higher.” So, not all altruism, then, but a glimmer of empathy. “Think of the people that aim low and still fail. There must be nothing worse than selling out and still being fucked.”

Gervais appears to have avoided selling out. He has not had his inward-tilting teeth fixed. He has not lost weight. And he still managed to bag the romantic lead in a Hollywood comedy. “Hang on,” he says, “it’s not a romantic lead.” Isn’t it? “It’s not a romantic lead in the sense of being a hunk you should take seriously. It’s hopefully not one of those vanity projects where you want to go: that’s ridiculous. When I work out and wear a toupee and lose weight and unironically get the girl, that’s when I’m trying to be a romantic lead. If I am a romantic lead, it has to be firmly in the mould of the unlikely loser.”

But his appearance at last month’s Emmys didn’t suggest an unlikely loser. He gave a speech to announce a set of nominees, but it ended up an extended ribbing of the US star of The Office, Steve Carell. (“Look at his stupid face ... I made you what you are and I get nothing back. Have you even been to see Ghost Town? I sat through Evan Almighty, now give me my Emmy back. Give me the Emmy. I’ll tickle you.”) It was the hit of the show, though only, Gervais says, “because the rest was so fucking dire,” and helped build rumors that he will present the Oscars come February.

The character Gervais presented at the Emmys — convinced of his own rightness — has some odd similarities to Pincus. It’s easy to imagine producers (witheringly dismissed in Gervais’ speech) taking that character aside and telling him to stop behaving like a jerk, just as one of Pincus’ colleagues does in Ghost Town. Is that something Gervais would do? “Yeah, but I don’t generally use a word like that.”

How would he word it? “Blokes usually say, ‘Stop being such a fucking cunt.’ It’s not Keats, but there is a certain poetry — you’ve got to take that one seriously.”

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the

Australia’s ABC last week published a piece on the recall campaign. The article emphasized the divisions in Taiwanese society and blamed the recall for worsening them. It quotes a supporter of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) as saying “I’m 43 years old, born and raised here, and I’ve never seen the country this divided in my entire life.” Apparently, as an adult, she slept through the post-election violence in 2000 and 2004 by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), the veiled coup threats by the military when Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) became president, the 2006 Red Shirt protests against him ginned up by

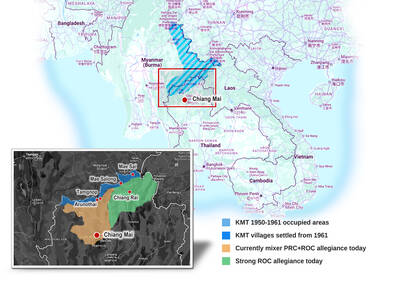

As with most of northern Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) settlements, the village of Arunothai was only given a Thai name once the Thai government began in the 1970s to assert control over the border region and initiate a decades-long process of political integration. The village’s original name, bestowed by its Yunnanese founders when they first settled the valley in the late 1960s, was a Chinese name, Dagudi (大谷地), which literally translates as “a place for threshing rice.” At that time, these village founders did not know how permanent their settlement would be. Most of Arunothai’s first generation were soldiers

Among Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) villages, a certain rivalry exists between Arunothai, the largest of these villages, and Mae Salong, which is currently the most prosperous. Historically, the rivalry stems from a split in KMT military factions in the early 1960s, which divided command and opium territories after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) cut off open support in 1961 due to international pressure (see part two, “The KMT opium lords of the Golden Triangle,” on May 20). But today this rivalry manifests as a different kind of split, with Arunothai leading a pro-China faction and Mae Salong staunchly aligned to Taiwan.