Paul Newman always wore his fame lightly, his beauty too. The beauty may have been more difficult to navigate, when he was young in the 1950s and still being called the next Marlon Brando, establishing his bona fides at the Actors Studio and on Broadway.

Yet Newman, who died at his home in Westport, Connecticut, on Friday, never seemed to resent his good looks, as some men did; instead, he shrugged them off without letting them go. He learned to use that flawless face, so we could see the complexities underneath. And later, when age had extracted its price, he learned to use time too, showing us how beauty could be beaten down and nearly used-up.

You see the dangerous side of his beauty in Hud, Martin Ritt’s irresistible if disingenuous 1963 drama about a Texas ranching family, in which Newman plays the womanizing son of a cattleman (the Hollywood veteran Melvyn Douglas), who’s hanging onto a fast-fading way of life. The movie traffics in piety: The father refuses to dig for the oil that might change the family’s fortunes because he doesn’t approve of sucking the land dry. Newman plays the son, Hud, and it’s his job to sneer at the old man’s naivete and to play the villain, which he does so persuasively that he ends up being the film’s most enduring strength.

A lot of reviewers clucked about Hud and Newman’s grasping bad-boy ways (the word they used then was materialism), but the camera loves this cowboy Lothario so much — or, rather, the actor playing him — that his father’s high-and-mighty ways don’t stand a chance. Nobody else much does, either: When Hud hits on family housekeeper (a smoky-voiced, smoking Patricia Neal), he sinks back in her bed and, with his nose deep in a daisy, asks with a leer, “What else you good at?” Rarely has the act of smelling a flower seemed as delectably dirty. It’s no wonder that Pauline Kael, who refused to buy just about anything else this movie was selling, gave Newman his due.

There are some men, Kael wrote, who “project such a traditional heroic frankness and sweetness that the audience dotes on them, seeks to protect them from harm or pain.” Newman did that for Kael, enough so that she was inspired to write about her own past and the California town that she “and so many of my friends came out of” — and, here, I think she means girlfriends — “escaping from the swaggering small-town hotshots like Hud.”

What’s striking is that what got Kael going wasn’t the actor or his performance but the man, who, because he seemed to offer up an intangible part of himself, something genuine and real, something we could take home, became a true movie star.

I don’t think Newman was ever as beautiful as he is in Hud. His lean, hard-muscled body seems to slash against the widescreen landscape, evoking the oil derricks to come, and the black-and-white cinematography turns his famous baby blues an eerie shade of gray. The character would be a heartbreaker if he were interested in breaking hearts instead of making time with the bodies that come with them. That’s supposed to make Hud a mean man, but mostly he seems self-interested. No one is tearing him apart, and Newman doesn’t try to plumb the depths with the role, which makes the character and the performance feel more contemporary than many of the head cases of the previous decade. He finds depths in these shallows.

Early in his career, Newman was often mistaken for Brando, so much so that he took to signing the other man’s autograph. Both studied at the Actors Studio and jumped to Hollywood, but there’s not much else to connect them beyond our demand for the Next Big Thing. The resemblance seems hard to grasp now, given their trajectories and how differently the two register onscreen: Brando sizzles, while Newman is as cool as dry ice. And unlike Brando, who at his death was often unkindly remembered for his baroque excesses, Newman seemed immune, bulletproof. (An exception: his support for Eugene McCarthy, which landed him on former US president Richard Nixon’s enemies list.) He had a talent for evasion.

It was a talent that served him well during the 1960s, the decade in which he picked up the mantle of Hollywood stardom that Brando had shrugged off. Newman was one of the dominating male screen figures of that decade, appearing in critical and commercial successes like Cool Hand Luke, a 1967 prison movie-cum-religious-allegory, and the 1969 Western Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, in which he found a partner in charm in Robert Redford. These days, 1969 is more often remembered for another buddy movie, Easy Rider, but Butch Cassidy may have had more lasting impact on the so-called New Hollywood, which struck gold with two photogenic male leads whose easy, breezy rapport helped transform rebellion into a salable, lucrative package.

Newman, who signed a contract with Warner Bros in the 1950s, was a transitional figure between the old Hollywood and the new. Warner foolishly put him in a ludicrous 1954 costume extravaganza called The Silver Chalice. He did better as the boxer Rocky Graziano in the 1956 biopic Somebody Up There Likes Me. His Lower East Side accent is so thick it could have been served on rye at Katz’s Delicatessen, but he holds the screen with his pretty-boy kisser and an intense, at times wild physical performance that suggests a terrific will behind that impeccable facade. He seems to be hurling himself at the camera, as if desperate to get our attention.

The roles improved, as did the performances, and suddenly he didn’t seem to be trying as hard. He’s silky smooth as a pool shark named Fast Eddie in Robert Rossen’s 1961 high-key drama The Hustler, in which Jackie Gleason, Piper Laurie and George C. Scott take turns stealing scenes. At first Newman seems outclassed by his co-stars — the film asks the actor, a nibbler rather than an outright thief, to do too much big acting. But he’s still awfully good. He seduces and repels by turn, pulling you in so you can watch him peel Fast Eddie’s defenses like layers of dead skin. It’s a wonder there was anything left by the time he revived the character 25 years later in The Color of Money.

He won an Oscar in 1987 for best actor for resurrecting Fast Eddie in that Martin Scorsese film, a piteously delayed response from his peers, who dangled six such nominations before giving up the prize. (Hedging its bets, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences had tossed Newman an honorary Oscar the year before.) He’s superb in The Color of Money, gracefully navigating its slick surfaces and periodically scratching beneath them, playing a variation on what had by then in movies like The Drowning Pool (1975), Slap Shot (1977) and The Verdict (1982) become a defining Newman type: the guy on the hustle who seems to have nothing much left but keeps his motor running, just in case.

The movies are not kind to older actors, and yet Newman walked away from this merciless business seemingly unscathed. During his second and third acts, he kept his dignity partly by playing men who seemed to have relinquished theirs through vanity or foolishness. Some of them were holding onto decency in an indecent world; others had nearly let it slip through their fingers.

Decency seems to have come easily to Newman himself, as evidenced by his philanthropic and political endeavors, which never devolved into self-promotion. It was easy to take his intelligence for granted as well as his talent, which survived even the occasional misstep. At the end of The Drowning Pool, a woman wistfully tells Newman, I wish you’d stay awhile. I know how she feels.

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the

Australia’s ABC last week published a piece on the recall campaign. The article emphasized the divisions in Taiwanese society and blamed the recall for worsening them. It quotes a supporter of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) as saying “I’m 43 years old, born and raised here, and I’ve never seen the country this divided in my entire life.” Apparently, as an adult, she slept through the post-election violence in 2000 and 2004 by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), the veiled coup threats by the military when Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) became president, the 2006 Red Shirt protests against him ginned up by

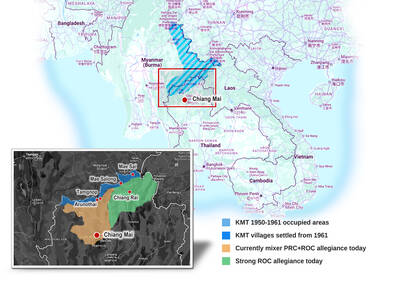

As with most of northern Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) settlements, the village of Arunothai was only given a Thai name once the Thai government began in the 1970s to assert control over the border region and initiate a decades-long process of political integration. The village’s original name, bestowed by its Yunnanese founders when they first settled the valley in the late 1960s, was a Chinese name, Dagudi (大谷地), which literally translates as “a place for threshing rice.” At that time, these village founders did not know how permanent their settlement would be. Most of Arunothai’s first generation were soldiers

Among Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) villages, a certain rivalry exists between Arunothai, the largest of these villages, and Mae Salong, which is currently the most prosperous. Historically, the rivalry stems from a split in KMT military factions in the early 1960s, which divided command and opium territories after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) cut off open support in 1961 due to international pressure (see part two, “The KMT opium lords of the Golden Triangle,” on May 20). But today this rivalry manifests as a different kind of split, with Arunothai leading a pro-China faction and Mae Salong staunchly aligned to Taiwan.