It would be understandable were John le Carre to sit back, plump up the laurels (if you can do that to laurels) and rest up. In a writing career spanning five decades he has, after all, defined the spy novel, lifting it into the realms of literature, and given us some of the most memorable characters, set pieces and films of the post-1945 era. But he is stubbornly, exuberantly determined to keep exploring, in a world beset with wholly new paranoias, the men and (equally crucially) women who do bad and good by stealth. His new novel is basically a tale of guilty anger — on the part of the Hamburg spies who failed so miserably to latch on to Mohammed Atta and his colleagues; and on the part of the Brits and the Yanks who, desperate for success, are prepared to crawl over anyone for the sake of one small triumph, one imam they can “turn.”

Into Hamburg, then, sneaks a tortured Russian, possibly a Chechen, with scars both mental and physical and, most pertinently, the key to a safety deposit box containing the substantial and wholly ill-gotten gains of his late and despised father, one of the KGB colonels who used Western banks to turn black money white in the dying days of Soviet Russia. Enter the likable but hapless owner of the British (but Hamburg-based) private bank that had been used for these “Lipizzaner” deals (the famous horses are born black but turn white with age). Enter a difficult, delicately drawn female human-rights lawyer who sees in Issa, the refugee, the chance to make amends for previous deportations she failed to prevent. Enter, sotto voce, at least three national espionage networks, watching and planning their three-dimensional chess. The Germans, led by the intensely affable Gunther Bachmann, the book’s finest character, see a chance to use Issa to compromise a “moderate” Muslim TV cleric whose charities follow some odd conduits. The Americans want to come in all guns blazing, not just figuratively. The Brits want to skulk, threaten, wheedle, double-cross and steal credit.

What Le Carre has always done terrifically is to capture the nuances of the spying game. His spooks are wonderful. You find yourself believing you are in that room, quietly rooting for whoever commands your allegiance at that moment. He paints the scene so fully in his own mind before writing that you forget you’re reading fiction: every cough, every glance, each sip of bottled water feels as if it were part of a scrupulously honest documentary. It is also a delight to read a man who believes in proper continuity, when so many lesser thriller writers have waiters arriving with the first course three seconds after the diners have met.

Where Le Carre falls down, I think, is in capturing the burgeoning (or is it?) love triangle between the pretty lawyer, the rich but rubbish banker and the (frankly unlikable) refugee. Did Issa boff Annabel? Will Tommy get her instead? Frankly, who cares? This too-huge subplot fails to grip, and simply points up how much more riveting the real action is. Le Carre’s minor characters are never less than spot-on, but his three main ones are oddly shoehorned into emotions that we, the readers, fail to share with them. (And besides, Issa is so annoying that if the gung-ho Americans ever did end up fitting him for a dinky orange boiler-suit, I don’t think too many readers would be weeping.)

But these failures aren’t too disastrous. Relish, instead, the knowledge this book imparts about the men who have learned to talk just below the level of hotel music, and say small things with huge import; about the impossible moral Mobius strip handed to Western liberals by Islamicist jihad. In A Most Wanted Man you are, unlike the modern world, in thrillingly deft, safe hands.

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the

Australia’s ABC last week published a piece on the recall campaign. The article emphasized the divisions in Taiwanese society and blamed the recall for worsening them. It quotes a supporter of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) as saying “I’m 43 years old, born and raised here, and I’ve never seen the country this divided in my entire life.” Apparently, as an adult, she slept through the post-election violence in 2000 and 2004 by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), the veiled coup threats by the military when Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) became president, the 2006 Red Shirt protests against him ginned up by

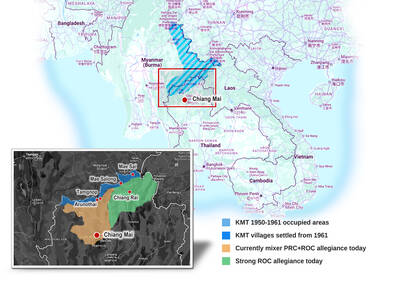

As with most of northern Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) settlements, the village of Arunothai was only given a Thai name once the Thai government began in the 1970s to assert control over the border region and initiate a decades-long process of political integration. The village’s original name, bestowed by its Yunnanese founders when they first settled the valley in the late 1960s, was a Chinese name, Dagudi (大谷地), which literally translates as “a place for threshing rice.” At that time, these village founders did not know how permanent their settlement would be. Most of Arunothai’s first generation were soldiers

Among Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) villages, a certain rivalry exists between Arunothai, the largest of these villages, and Mae Salong, which is currently the most prosperous. Historically, the rivalry stems from a split in KMT military factions in the early 1960s, which divided command and opium territories after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) cut off open support in 1961 due to international pressure (see part two, “The KMT opium lords of the Golden Triangle,” on May 20). But today this rivalry manifests as a different kind of split, with Arunothai leading a pro-China faction and Mae Salong staunchly aligned to Taiwan.