In a country that has displayed a positive obsession with recording its history on plaques and standing stones over thousands of years, China’s so-called Nestorian Monument is still its best-known inscribed tablet in the West. Unearthed in Xian in 1625, it’s dated 781 and pays tribute, in 1,800 Chinese characters and passages written in Syriac, to a “luminous religion” and its propagation in the Middle Kingdom. It bears a cruciform design above its title and describes a belief system that had come to China from afar and included a three-in-one god, a virgin birth, an evil force called Sadan, and ministers who traveled the earth and, making no distinction between rich and poor, brought the good news to all and sundry.

This has always been understood as referring to the Nestorian Church, a branch of Christianity that held a dissenting view of the dual nature (both man and god) of Jesus, and was widely active in Asia during the first millennium. Genghis Khan’s mother was a Nestorian Christian, and the church used Syriac for its liturgy. A notably tolerant attitude to imported religions held sway under several emperors during the Tang Dynasty, but suddenly all foreign religious sects were proscribed in China in the years 842 to 845, and the inscribed stone was probably buried then in order to hide it.

Michael Keevak is a professor at the National Taiwan University. Although his usual area of study is English Literature (his book Sexual Shakespeare was reviewed in the Taipei Times on Jan. 27, 2002), he has put his mind in this new work to the ways this famous Chinese monument was received in the West over the 300 years from its rediscovery. All the illustrations in The Story of a Stele, except for three photos taken by the author on a trip to view the monument, are from books in National Taiwan University’s library, so it’s reasonable to assume that Keevak’s interest in this topic began with his involvement in the preservation of the older books held there, an endeavor described in the Taipei Times on June 9, 2002.

What Keevak here seeks to show is that the Westerners saw, not something that in reality represented a short-lived incident within Chinese history, but a reflection of their own concerns. “The tablet was not even the real object of attention,” he writes, “just as China and Chinese culture or the Chinese language were constantly being pushed into the background of European preoccupations with religious conversion, cultural superiority and monetary profit.”

Nevertheless, it’s hardly surprising that the Europeans, and the Jesuits in particular, found the monument of enormous significance. After all, a 17th century Chinese emperor must have been reflecting the views of many when he exclaimed it was strange that this Western god had neglected his great empire while bestowing his sacred revelation on so many insignificant barbarian kingdoms. This tablet proved that China hadn’t been neglected after all, and that the gospel had indeed been propagated within the Celestial Empire from comparatively early times.

Of course there were problems. Some of the inscribed text echoes Buddhist and other Asian classic texts, for example, and remains obscure even today. In addition, the Jesuits had to try to demonstrate that Nestorian Christianity was identical with the brand they were themselves preaching, which wasn’t entirely the case. Even so, the Nestorian Monument must remain a major historical document, wherever in the world it’s looked at from, and Professor Keevak sometimes has a hard time attempting to persuade the reader otherwise.

Nor has its significance faded. The book concludes with a perhaps over-indulgent treatment of a recent tribute to the monument’s significance, Martin Palmer’s 2001 New Age best-seller The Jesus Sutras: Rediscovering the Lost Scrolls of Taoist Christianity. That some of the world’s major religions can in fact be seen as interrelated is good news in an age of globalization — Keevak elsewhere refers to the annoyance afforded to 19th century Protestants by the strange similarities between Roman Catholic and Buddhist rituals, both of course equally idolatrous in their eyes.

This is a pleasantly written, erudite work that will send readers in many interesting directions. Not only will they be led to investigate Nestorian Christianity itself, but also such topics as the medieval legend of Prester John, the Christian church supposedly founded by the apostle Thomas on the southern tip of India, and even the exact location of the Earthly Paradise. (A 17th century Dominican missionary, Domingo Navarrete, was so enamored of China and the Chinese that he speculated that the Garden of Eden itself must surely have been located somewhere within Chinese territory).

An item of information that will be of particular interest in Taiwan is that immediately on coming to power in 1912, Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙) cited the Nestorian Monument as representing the China open to all foreign influences that he wanted to recreate in the Republic of China.

If what you value are expansiveness, enthusiasm and a broad overview of affairs, then Keevak is not your man. His specialty appears to be the close reading of little-known texts, together with a startled surprise at the pretentiousness of authors ancient and modern. He won’t lead you to read the books he describes so much as dissect them, their absurdities always included, on your behalf.

The Story of a Stele is a thorough and extremely learned treatment of the narrow subject the author opts to consider. Its value to scholars will be great, while others will be led to investigate a wide range of fascinating topics after perusing it.

From the last quarter of 2001, research shows that real housing prices nearly tripled (before a 2012 law to enforce housing price registration, researchers tracked a few large real estate firms to estimate housing price behavior). Incomes have not kept pace, though this has not yet led to defaults. Instead, an increasing chunk of household income goes to mortgage payments. This suggests that even if incomes grow, the mortgage squeeze will still make voters feel like their paychecks won’t stretch to cover expenses. The housing price rises in the last two decades are now driving higher rents. The rental market

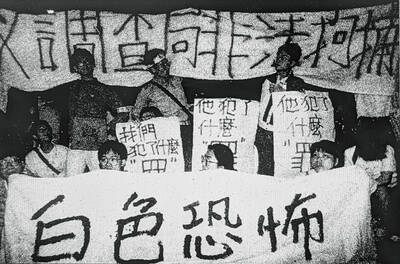

July 21 to July 27 If the “Taiwan Independence Association” (TIA) incident had happened four years earlier, it probably wouldn’t have caused much of an uproar. But the arrest of four young suspected independence activists in the early hours of May 9, 1991, sparked outrage, with many denouncing it as a return to the White Terror — a time when anyone could be detained for suspected seditious activity. Not only had martial law been lifted in 1987, just days earlier on May 1, the government had abolished the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of National Mobilization for Suppression of the Communist

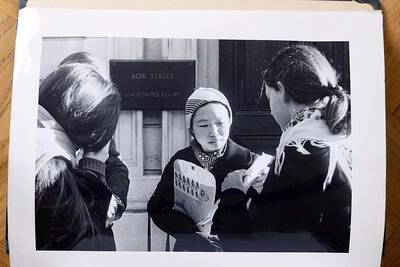

Fifty-five years ago, a .25-caliber Beretta fired in the revolving door of New York’s Plaza Hotel set Taiwan on an unexpected path to democracy. As Chinese military incursions intensify today, a new documentary, When the Spring Rain Falls (春雨424), revisits that 1970 assassination attempt on then-vice premier Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國). Director Sylvia Feng (馮賢賢) raises the question Taiwan faces under existential threat: “How do we safeguard our fragile democracy and precious freedom?” ASSASSINATION After its retreat to Taiwan in 1949, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) regime under Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) imposed a ruthless military rule, crushing democratic aspirations and kidnapping dissidents from

Fundamentally, this Saturday’s recall vote on 24 Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers is a democratic battle of wills between hardcore supporters of Taiwan sovereignty and the KMT incumbents’ core supporters. The recall campaigners have a key asset: clarity of purpose. Stripped to the core, their mission is to defend Taiwan’s sovereignty and democracy from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). They understand a basic truth, the CCP is — in their own words — at war with Taiwan and Western democracies. Their “unrestricted warfare” campaign to undermine and destroy Taiwan from within is explicit, while simultaneously conducting rehearsals almost daily for invasion,