Imagine an election that pits Candidates A, B and C against one another. There are 10,000 voters. Candidate A is the clear favorite of 9,999 of them. But Candidate A is nonetheless defeated. How is it possible for Candidate B to beat the other two?

William Poundstone's Gaming the Vote arrives amid unusually high reader interest in equitable voting. And Poundstone is a clear, entertaining explicator of election science. He easily bridges the gaps between theoretical and popular thinking, between passionate political debate and cool mathematical certainty. These dichotomies can be drastic. If politics is a realm in which emotions run high, he notes, mathematics is "one of the few fields where it doesn't matter what other people think."

Social choice theory is a field of scholarship that analyzes voting patterns in the abstract. The resulting election strategies have become so Machiavellian, Poundstone says, that political consultants are as interested in backhandedly hurting some candidates as in helping others.

"Were these new campaign techniques a genetically engineered tomato," he writes of such tactics, which are colorfully illustrated here, "they might command more attention than they have. They have gone largely unnoticed by the public, the media, and nearly everyone except the campaign strategists and their clients." Gaming the Vote provides a lively remedy for that situation.

Poundstone's book asks one overriding question: "Is it possible to devise a fair way of voting, one immune to vote splitting?" The answer requires some historical context: a brief history of elections gone terribly awry.

Poundstone's chronicle of

spoilers concentrates on presidential elections that delivered the opposite outcome from the one most voters seemed to prefer. This goes from explaining how abolitionist vote-splitting in 1844 put the slave-owner James Polk in the White House to showing how a consumer advocate, Ralph Nader, helped to elect "the favored candidate of corporate America," President George W. Bush, in 2000.

Since at least five out of 45 presidential elections have gone to the second-most-popular candidate because of spoilers, Poundstone calculates a failure rate of more than 11 percent for our voting system. "Were the plurality vote a car or an airliner," he writes about this traditional method, "it would be recognized for what it is - a defective consumer product, unsafe at any speed."

As political consultants become as scientific as they are ruthless, Poundstone maintains, "we are witnessing a bipartisan mainstreaming of the spoiler effect as a tool for political strategizing." Regard these manipulators as hackers corrupting a software system, and you arrive at a clear conclusion: The software needs to be changed. Gaming the Vote offers lively explanations of mathematically feasible alternatives.

That idea that voting methods can be gamed has been so warmly embraced that Donald Saari, a prominent theorist, says: "For a price, I will come to your organization just prior to your next important election. You tell me who you want to win. I will talk with the voters to determine their preferences over the candidates. Then I will design a 'democratic voting method' which involves all candidates. In the election, the specified candidate will win." Saari was joking, but some politicians understood this to be a serious offer.

In Gaming the Vote, Poundstone enumerates some of the major theoretical systems that could reshape voting. Two of the most influential methods are traced back to rival 18th-century French intellectuals who devised conflicting systems and also displayed a prescient scholarly hostility.

The Marquis de Condorcet, an important theorist in the field, once said of Jean-Charles de Borda, who advocated a weighted ballot on which voters ranked candidates in descending order: "Some of his papers display talent, although nothing follows from them and nobody has ever spoken of them or ever will." This same collegiality is found among rival voting theorists even today.

Among the points explained by Gaming the Vote is that the mad-tea-party absurdities of voting systems actually do owe something to Lewis Carroll. (Under his real name, the Reverend Charles Dodgson, he analyzed election paradoxes and advocated treating voting as a game of skill.) Poundstone cites leading scholars, among them Steven Brams and the Nobel laureate Kenneth Arrow, both of whom give their endorsement to this valuable book. He describes alternative voting systems known as Approval, Range, Cumulative, Condorcet and Instant-Runoff voting. Only rarely and humorously must he render this confusing.

"The thing is, it's impossible to explain Condorcet voting any further without talking about cycles and 'beat-paths' and 'cloneproof Schwartz sequential dropping,'" he says. "This is where the android's mask falls off and it's all wires and microchips inside. Non-PhD's run screaming for the exits. So far, Condorcet voting has tended to appeal to the kind of people who can write Javascript code for it."

Poundstone's preference is for a system called range voting, advanced by Warren Smith, a mathematician. Range voting, in which voters rate the candidates numerically, is akin to the weighted, collective tallies used for Internet product ratings, the Web site Hot or Not (which has elicited more votes than all American presidential contests combined) and restaurant guides shaped by consumers.

Range voting outstrips yes-or-no plurality voting in revealing voters' nuanced opinions. It has been admired even by Ralph Nader - and that, Poundstone writes with typical dry panache, "is something like a spirochete endorsing penicillin." Nader's spoiler effect is exactly what Gaming the Vote means to assail.

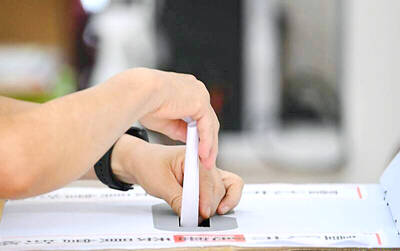

Speaking of spoilers, the way Candidate A could lose with 9,999 votes would be on an approval ballot that allowed each voter to list more than one choice. If A alienated even one voter, while B, as a mediocrity, appealed to all of them, then B would be elected. If approval ballots had been used in 1992, and Ross Perot had appeared on every single ballot, and at least one voter chose not to vote for Bill Clinton or George Bush, President Perot would be in the history books. In the opinion of Gaming the Vote, this is reason enough to explain why voting systems warrant close scrutiny and major change.

Behind a car repair business on a nondescript Thai street are the cherished pets of a rising TikTok animal influencer: two lions and a 200-kilogram lion-tiger hybrid called “Big George.” Lion ownership is legal in Thailand, and Tharnuwarht Plengkemratch is an enthusiastic advocate, posting updates on his feline companions to nearly three million followers. “They’re playful and affectionate, just like dogs or cats,” he said from inside their cage complex at his home in the northern city of Chiang Mai. Thailand’s captive lion population has exploded in recent years, with nearly 500 registered in zoos, breeding farms, petting cafes and homes. Experts warn the

No one saw it coming. Everyone — including the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) — expected at least some of the recall campaigns against 24 of its lawmakers and Hsinchu Mayor Ann Kao (高虹安) to succeed. Underground gamblers reportedly expected between five and eight lawmakers to lose their jobs. All of this analysis made sense, but contained a fatal flaw. The record of the recall campaigns, the collapse of the KMT-led recalls, and polling data all pointed to enthusiastic high turnout in support of the recall campaigns, and that those against the recalls were unenthusiastic and far less likely to vote. That

The unexpected collapse of the recall campaigns is being viewed through many lenses, most of them skewed and self-absorbed. The international media unsurprisingly focuses on what they perceive as the message that Taiwanese voters were sending in the failure of the mass recall, especially to China, the US and to friendly Western nations. This made some sense prior to early last month. One of the main arguments used by recall campaigners for recalling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers was that they were too pro-China, and by extension not to be trusted with defending the nation. Also by extension, that argument could be

The centuries-old fiery Chinese spirit baijiu (白酒), long associated with business dinners, is being reshaped to appeal to younger generations as its makers adapt to changing times. Mostly distilled from sorghum, the clear but pungent liquor contains as much as 60 percent alcohol. It’s the usual choice for toasts of gan bei (乾杯), the Chinese expression for bottoms up, and raucous drinking games. “If you like to drink spirits and you’ve never had baijiu, it’s kind of like eating noodles but you’ve never had spaghetti,” said Jim Boyce, a Canadian writer and wine expert who founded World Baijiu Day a decade