Much of Asia can still be rightly described as displaying a "massage culture." Sex, nominally disguised as massage, is offered by the attractive but impecunious young to the better-off males in establishments that have, to local eyes, nothing disreputable about them. European men discovered this age-old phenomenon with a sense of disbelief - its equivalents had long been banished, certainly in Anglo-Saxon countries, under the various manifestations of Puritanism. Thailand went on to built a tourism industry on its immemorial leisure-time habits, while in Japan the ancient structures were modified only by the arrival of general affluence. This has led to nostalgia there for the old ways, and in particular a fascination with the lifestyle and traditions of the geishas.

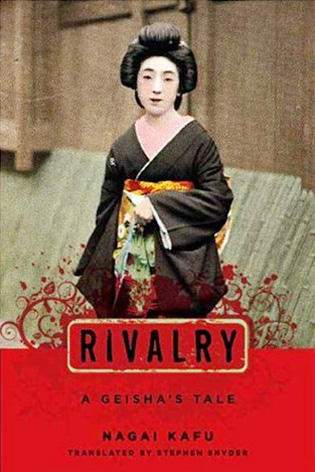

Rivalry: A Geisha's Tale, fresh from Columbia University Press in an English version by Stephen Snyder, is the first ever translation of the full text of the masterpiece of the early 20th century novelist and short-story writer Nagai Kafu. An earlier translation was only of a commercial edition that didn't include long erotic passages added later by the author for a private printing - he knew in advance that they'd be unacceptable to the government censor.

Nagai Kafu is a fascinating figure. Originally an editor of literary magazines specializing in the newly-fashionable French naturalism, he abandoned that work in order to embark on a life investigating Tokyo's erotic underworld. This was partly done, no doubt, for its own sake, but it was also undertaken in a spirit of devotion to the ethos of the old, pre-modern Japan, the traditions of which Kafu felt were in part preserved in the teahouses and theaters around which the geishas and other women of the night circulated.

Rivalry is a wonderful novel, with clearly distinguished characters, a swift narrative style, rich descriptions and incisive analyses of feelings and motives. It's set around 1912, and evokes a capital city already equipped with telephones, newspapers, cigarettes and trams. There are stockbrokers, new sessions of parliament and year-end sales. But still defining the life in the pleasure quarters are the ways of the Edo period which had ended over 40 years before, so that geishas continue to preside over the tea ceremony, dress with astonishing formality, and entertain rich businessmen, initially at least with performances on the shamisen.

Kafu understands perfectly well that differences of money, and hence of power, lie behind the sexual games his characters play. The geishas are contracted to the houses they work out of, and one of their main ambitions is to find a patron who will pay off this debt and set them up in financial independence. But at the same time they are young and sensual beings, falling in love with kabuki actors of their own age even while conducting by no means platonic affairs with their older clients. This is part of the rivalry of the title, and it's the main character's love for a young actor that triggers the fury of her patron, Yoshioka, even though he's by this time become tired of their sexual relationship and is looking around for new pleasure elsewhere.

It's strange that a novel as good as this has remained unpublished in English in its complete form for so long. It's true that for many decades after the extended edition was published in Japan (in 1917) passages from it would not have been permitted in, for instance, the UK. There are by no means disapproving references to oral and anal sex, for example, and the writing in general has an open-mindedness about it that is extremely refreshing. Even so, it has been through Arthur Golden's 1997 bestseller Memoirs of a Geisha - also a novel, though cast as an autobiography - that most modern readers have gotten to know about the geisha traditions. Kafu's older classic, by contrast, will please aesthetes and lovers of genuine literature far more.

There's a long-standing tradition among Japan specialists of insisting that geishas were high-class entertainers most of whom would never allow the men they entertained to lay a finger on them. This is a long way from Kafu's view, and he was in an ideal position to know. Indeed, the description of one particularly outrageous senior geisha, Kikuchiyo, is so replete with sexual detail that I had to read it twice before I could believe my eyes.

But Kafu was no smut-peddler. At heart he was a lover of ancient Chinese poetry, like the writer Kurayama Nanso in the novel. Indeed, one of the characters he mocks most vigorously is Yamai, the editor of a new magazine specializing in pornographic photos. But then one of the attractions of this wonderful book is its range, even given its relative brevity and concision. There are as many different types of character, and of emotion, as there are in Tolstoy, even though Kafu's true masters were probably Maupassant and Turgenev, social realists with a sympathetic eye for subtleties of situation and nuances of feeling.

Kafu was an aesthete fascinated by sex, and predictably he had his own theory of desire. Whereas men of old sought to prove their masculinity in war or hunting, in the modern world they seek to do it by success in the fields of business and sexual predation. Yoshioka is his prime example of this, a handsome married man possessed of "an endless repertoire of obscene tricks," adept at concluding affairs, and endlessly seeking out new conquests "from girls of sixteen to women past forty." He finally finds his match in the frankly sensual Kikuchiyo.

Stephen Snyder is to be thanked both for translating this half-forgotten novel at all, and for doing it so compellingly. He is, incidentally, also the author of a critical book on Kafu entitled, appropriately enough, Fictions of Desire.

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them