Viewed from the air, the vast, cool forests of the Kampar peninsula on Indonesia's Sumatra island are a world away from China's belching factories or America's clogged freeways.

But appearances can be deceptive.

Most of this 400,000 hectare peninsula is peatland: dense, swampy forest that, when healthy, efficiently soaks up greenhouse gases from the world's worst polluters.

When drained, cleared or burned, however, this wilderness transforms into one of the worst climate vandals, releasing six to nine times the amount of carbon stored in regular equatorial forests.

Swamps have not traditionally held the same ecological sex appeal as, say, doe-eyed wildlife. But as nations prepare for a major global conference on climate change in Indonesia next month, the world's focus is changing.

The Dec. 3 to Dec. 14 UN summit on the resort island of Bali will see international delegates thrash out a framework for negotiations on a global regime to combat climate change when the current phase of the Kyoto Protocol ends in 2012.

A figure from the Indonesia-based Center for International Forestry Research puts deforestation at around 25 percent of all man-made carbon dioxide emissions.

Avoiding emissions from deforestation has so far been left out of the Kyoto Protocol on climate change, which focuses instead on reducing emissions from sources such as industry and transport.

Widespread deforestation has made Indonesia the third largest emitter of carbon in the world, the contribution coming most dramatically in the form of near-annual forest fires on islands such as Sumatra and Borneo.

The fires, which send choking smoke as far as Singapore and Malaysia, are for the most part caused by the clearing of peatlands. And the destruction of Indonesia's peatlands accounts for four percent of total global greenhouse gas emissions, according to Greenpeace.

Peatlands are not just a threat when they are burning. A flight over Kampar reveals scars of cleared land gouged from the forest, linked with canals built to transport legal and illegal logs to inland mills.

Much of the carbon released from peatland swamps is the result of draining so the land, or the logs, can be used, says Jonotoro, a peatlands expert at the forestry ministry and an independent consultant.

As the water level drops, more and more of the stock of carbon is released into the atmosphere.

In clear-cut areas, the temperature can rise dramatically in the dry months between July and September to around 70°C, up from a usual cool average of 28°C.

"If the peat is already dry, it's impossible to make it wet," Jonotoro said.

Peatland is made up of a waterlogged store of semi-decomposed vegetation, which squelches underfoot. The deeper the peatland - it can stretch to a depth of more than 15m - the more carbon it holds.

If set on fire, dry peatland can burn for weeks - the fire can be extinguished on the surface, only to continue burning underground and reappear the next day.

In Indonesia, the main driver for the destruction of peatlands is the world's appetite for wood, pulp and palm oil.

The best place for plantations is dry land, but as the rush for Indonesia's last wildernesses continues to turn much of the countryside into a landscape of industrial uniformity, any land will do.

At the western end of Kampar sits Pangkalan Kerinci, home of a massive pulp and paper mill belonging to Asia Pacific Resources International (APRIL).

The mill - and the manicured company town that surrounds it - is the nerve center of a sprawling acacia plantation, much of which is on peatland.

APRIL is keen to boost its environmental credentials, running a tagging system to prevent illegal logging. Two of its security guards were killed in a 2002 confrontation with illegal loggers.

Still, seven of APRIL's partner companies are under investigation for illegally cutting forests.

A cornerstone of APRIL's green efforts is water management in its peatland plantations. At its nearby Pelalawan plantation, a 1,100km network of canals regulates water levels over 100,000 hectares of planted forest.

The goal of the management is to reduce emissions from the peatland beneath, explained Jouko Virta, head of APRIL's global fiber supply. By keeping the water table at the highest level tolerated by the plantation trees, Virta says carbon dioxide emissions from the peatland can be reduced by 80 percent.

The company is now pursuing an audacious plan to push into Kampar, converting more than 100,000 hectares around the peninsula's perimeter into more plantations, while leaving the center untouched.

APRIL says the move will reduce carbon emissions, since much of this perimeter is already heavily degraded, either by illegal loggers or old concessionaires.

By installing their own plantations and managing them responsibly, they believe they will keep illegal loggers from penetrating further inland.

"National parks are the happiest hunting grounds for illegal loggers, and the only way you can protect them is by building barriers," Virta said.

WWF reserved judgment on APRIL's plan, saying they needed to see evidence that the Kampar ring is really as degraded as the company says, and that emissions can actually be reined in as much as they say.

"I think we need to see the scientific analysis," said Nazir Foead, WWF's policy and corporate engagement director, adding that the organization was aiming to complete its own analysis by the Bali meeting next month.

Consultant Jonotoro is unconvinced by APRIL's optimism and said acacia plantations will never be a success on Kampar's nutrient-poor peatland.

"The main point of why they chose this area is because they need natural timber, big hardwood timber" for their mills, he said, referring to their legal practice of felling and processing the trees from their concessions before planting.

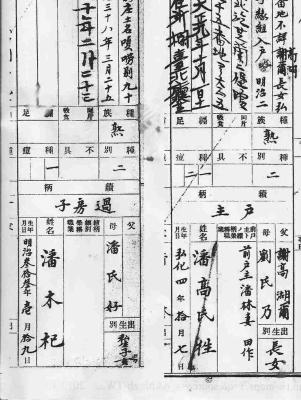

Feb. 9 to Feb.15 Growing up in the 1980s, Pan Wen-li (潘文立) was repeatedly told in elementary school that his family could not have originated in Taipei. At the time, there was a lack of understanding of Pingpu (plains Indigenous) peoples, who had mostly assimilated to Han-Taiwanese society and had no official recognition. Students were required to list their ancestral homes then, and when Pan wrote “Taipei,” his teacher rejected it as impossible. His father, an elder of the Ketagalan-founded Independence Presbyterian Church in Xinbeitou (自立長老會新北投教會), insisted that their family had always lived in the area. But under postwar

In 2012, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) heroically seized residences belonging to the family of former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁), “purchased with the proceeds of alleged bribes,” the DOJ announcement said. “Alleged” was enough. Strangely, the DOJ remains unmoved by the any of the extensive illegality of the two Leninist authoritarian parties that held power in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Taiwan. If only Chen had run a one-party state that imprisoned, tortured and murdered its opponents, his property would have been completely safe from DOJ action. I must also note two things in the interests of completeness.

Taiwan is especially vulnerable to climate change. The surrounding seas are rising at twice the global rate, extreme heat is becoming a serious problem in the country’s cities, and typhoons are growing less frequent (resulting in droughts) but more destructive. Yet young Taiwanese, according to interviewees who often discuss such issues with this demographic, seldom show signs of climate anxiety, despite their teachers being convinced that humanity has a great deal to worry about. Climate anxiety or eco-anxiety isn’t a psychological disorder recognized by diagnostic manuals, but that doesn’t make it any less real to those who have a chronic and

When Bilahari Kausikan defines Singapore as a small country “whose ability to influence events outside its borders is always limited but never completely non-existent,” we wish we could say the same about Taiwan. In a little book called The Myth of the Asian Century, he demolishes a number of preconceived ideas that shackle Taiwan’s self-confidence in its own agency. Kausikan worked for almost 40 years at Singapore’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, reaching the position of permanent secretary: saying that he knows what he is talking about is an understatement. He was in charge of foreign affairs in a pivotal place in