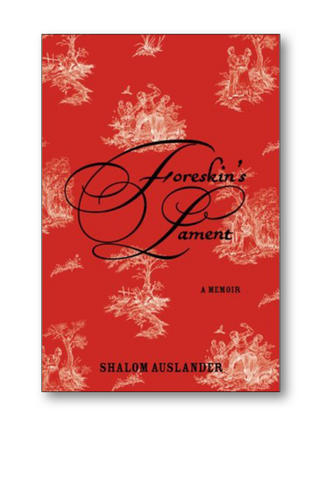

Shalom Auslander ends Foreskin's Lament, his memoir of growing up in, and eventually breaking away from, the Orthodox Jewish community, not with an acknowledgments page but with a list of people God might consider punishing instead of the author's family.

Auslander is no longer observant, but he is still a believer, and he believes in a wrathful, vengeful God who takes things personally and is not at all pleased when someone leaves the fold and writes an angry and very funny book about it.

"The people who raised me will say I am not religious," he writes. "They are mistaken." He adds: "I am painfully, cripplingly, incurably, miserably religious, and I have watched lately, dumbfounded and distraught, as around the world, more and more people seem to be finding gods, each more hateful and bloody than the next, as I'm doing my best to lose Him. I'm failing miserably."

On the second day of the Rosh Hashana holiday last month, Auslander visited Monsey, a village in Rockland County, New York, for the first time in years. Driving down the New York State Thruway from his new home near Woodstock, he worried that God might take this occasion to snare him in a fatal car wreck. He had even rented a sport utility vehicle, rather than risk being caught in the family wheels on a day when no observant Jew would even think of driving. "It was in the back of my mind the whole time," he said. "That would be a great punch line - for me to die in Monsey just as the book is coming out. There is no sicker comic than God."

Most people were on foot that day in Monsey, walking to and from the village's many synagogues. There were mothers in long dresses and snoods pushing infants in strollers, with boys in suits and yarmulkes skipping alongside; men in black hats and prayer shawls, and some wearing fur hats, breeches and white silk stockings.

"It's not just whether you're Jewish or not - there's a whole checklist," Auslander said, trying to explain the differences among the various groups. "It's like gang symbols. Your clothing, your hat, how you wear your payess," or sidelocks. "This is Crips territory here," he went on, "and just being in a car automatically makes you a Blood." He added: "I try sometimes to see myself through their eyes - as someone who has made a huge mistake. On the other hand, what if the big joke is that God has nothing to do with any of this, and doesn't care about it at all?"

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Pausing at a stop sign or to let some people cross the street, Auslander did draw an occasional disapproving glance. But otherwise the morning passed uneventfully as he cruised through the leafy streets of Monsey, its neighborhoods of split-levels, raised ranches and the occasional stuccoed McMansion resembling any other Rockland County suburb unless you look carefully. Auslander pointed to the many yeshivas and synagogues, some quartered in ordinary houses, and to driveways crammed with Big Wheels and plastic playhouses: a sign, he said, of Orthodox families with lots of children.

"It all feels very Twilight Zone to me," he said. "It seems more and more odd and more and more familiar at the same time." He paused outside a house where he used to baby-sit. "The family that used to live here was named Kafka," he said. "I used to wonder about that when I started reading him. It was like, 'Do you know the Goldbergs from Long Island? Do you know the Kafkas from Prague?'"

On Maple Avenue he came to the Yeshiva of Spring Valley, where he went to school for a time. "Do you see that Hebrew lettering?" he said. "It says: 'Please join us for a reading by Shalom Auslander. Bring your bags of rocks.'" Auslander grew up on the other end of town, which used to be less religious, and looping around his own street, a cul-de-sac called Arrowhead Lane, he was astonished to find, next to his old house, a holdout: a ranch house with a John 3:16 sign on the lawn. Nearby was a landmark he calls the Stone of Pornography in Foreskin's Lament: a boulder behind which he used to find a seemingly inexhaustible store of skin magazines, ditched presumably by a guilty commuter heading home. No porn this time, but there was a discarded box of non-kosher cookies.

Pornography, which Auslander eventually imported by the sackful, was part of his secret life in Monsey, both an escape and a source of anxiety. So were marijuana, orgies of non-kosher fast food and shoplifting expeditions. To a certain extent, he always felt like an outsider in the Orthodox world, he says now, but his escape proceeded by fits and starts, in spurts of rebellion and then periods of appeasement.

"The big discovery for me was that there's a whole world out there," he said. "That there's no reason to be terrified of the Nanuet Mall and, even worse, no reason to be scornful of it." But it took him years, including a stint as a bearded, fedora-wearing student in Israel and a subsequent gig as a weed-puffing shomer, or ritual corpse watcher, in New York, to arrive at his current, uneasy state of truce.

He tried ignoring God, and also compromising with him. As a teenager, he writes in Foreskin's Lament, which goes on sale this week, he once rode his bike to Caldors on Saturday but then found himself unable to further violate the Sabbath by activating the electric-eye door opener. In the early 1990s he was married and living in Teaneck, New Jersey, working in an ad agency and just getting started as a writer. One Saturday he walked all the way to Madison Square Garden to see a game during the Stanley Cup playoffs. God punished him by making the Rangers lose.

"It's ridiculous that I feel the way I do," he said at the end of his drive in Monsey. "That I have this cartoonish view of God as someone who rewards and punishes. I feel like a fool when I read someone like Richard Dawkins," he said, referring to the British atheist and evolutionary biologist. "But let's trade childhoods." Intellectually, he said, he understood Dawkins, but "emotionally I'm not there at all."

He went on to compare himself, jokingly, to Moses. "There are two ways you can look at that story," he said. "Moses makes one mistake and God shoots him in the head - he'll never get to the Promised Land. But you can also say that he almost makes it and that his children will. I like finding the dark upside, and that's why I ended the book with my son's first birthday. I didn't get free, but maybe he does."

Wooden houses wedged between concrete, crumbling brick facades with roofs gaping to the sky, and tiled art deco buildings down narrow alleyways: Taichung Central District’s (中區) aging architecture reveals both the allure and reality of the old downtown. From Indigenous settlement to capital under Qing Dynasty rule through to Japanese colonization, Taichung’s Central District holds a long and layered history. The bygone beauty of its streets once earned it the nickname “Little Kyoto.” Since the late eighties, however, the shifting of economic and government centers westward signaled a gradual decline in the area’s evolving fortunes. With the regeneration of the once

Even by the standards of Ukraine’s International Legion, which comprises volunteers from over 55 countries, Han has an unusual backstory. Born in Taichung, he grew up in Costa Rica — then one of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies — where a relative worked for the embassy. After attending an American international high school in San Jose, Costa Rica’s capital, Han — who prefers to use only his given name for OPSEC (operations security) reasons — moved to the US in his teens. He attended Penn State University before returning to Taiwan to work in the semiconductor industry in Kaohsiung, where he

In February of this year the Taipei Times reported on the visit of Lienchiang County Commissioner Wang Chung-ming (王忠銘) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a delegation to a lantern festival in Fuzhou’s Mawei District in Fujian Province. “Today, Mawei and Matsu jointly marked the lantern festival,” Wang was quoted as saying, adding that both sides “being of one people,” is a cause for joy. Wang was passing around a common claim of officials of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the PRC’s allies and supporters in Taiwan — KMT and the Taiwan People’s Party — and elsewhere: Taiwan and

On May 2, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), at a meeting in support of Taipei city councilors at party headquarters, compared President William Lai (賴清德) to Hitler. Chu claimed that unlike any other democracy worldwide in history, no other leader was rooting out opposing parties like Lai and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). That his statements are wildly inaccurate was not the point. It was a rallying cry, not a history lesson. This was intentional to provoke the international diplomatic community into a response, which was promptly provided. Both the German and Israeli offices issued statements on Facebook