He goes by only one name, Herman, and the images he makes have become recognized around the world, in all sorts of places, ranging from club logos to monumental icons. He is in Taiwan to launch a small show at the German Cultural Center here in Taipei. This is Herman's first visit to Taipei, and in his optimistic way, he is sure that from small things, great things will grow.

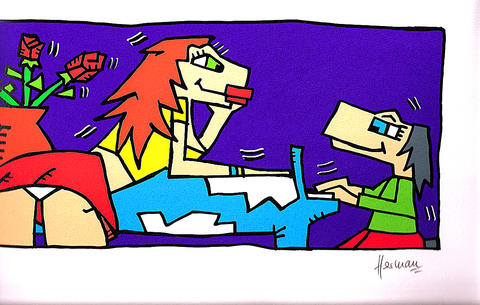

His paintings have a rough, simplistic look, but are full of verbal and pictorial humor. A professional cartoonist, Herman gave up his battle against the big cartoon syndicates, and decided to adopt a style of drawing that would differentiate him from the smooth, fluid lines of comic strips such as Garfield and Alfie.

His images are now notable for their jagged lines, which make them distinctive, as does the direct, innocent humor. It is this innocence and simplicity that is behind their appeal to a wide audience all over the world.

PHOTO: IAN BARTHOLOMEW, TAIPEI TIMES AND COURTESY OF HERMAN

"Lots of artists have tried to imitate me, but it doesn't work," Herman said in an interview with the Taipei Times last Tuesday. "When I paint a picture, it is like I write the words ... for me, when I paint, it is like writing. All that I put inside the picture comes out if you like it and look at it. This is perhaps the reason for its success. They don't see the edgy (jagged lines), but they see the round meanings behind them."

Herman's work, often initiated on a monumental scale, is then reproduced in limited-edition prints. These are the tools with which he conducts his charity work, auctioning them at various events where they often fetch high prices.

His painting Angel, stands 50m high, and at its base there is a button with a counter attached. "[People] can press the button and can be counted as someone who wishes for peace. If lots of people push the button, there is the addition of many people looking for peace, and the wishes come up to the universe, and then float back down into the world. I would like to make a network with this angel and the counter, ... but you need sponsors, for it is a lot of work." A limited edition of an A4 silk-screen print signed by the artist fetches around US$112.

Herman is unabashed at his commercial success. "In Germany, to go the museum way, you must be quiet and shy and paint two pictures a year. But there is only a small community who likes it. When many people like my work, I am commercial: I don't understand this." He talks about merchandising his images in ways that would make the quiet, shy, two-pictures-a-year artist blush, but Herman responds that "I do not make some nobody-understanding pictures ... . I catch some of people's smallest wishes, what everybody wants. It is not a marketing strategy. I do not think in marketing terms. At first, I paint a picture because inside there is something that has to come out, but after that, it is not for me, this picture. It is for anybody. Or everybody."

Herman's language of colors and lines translates all around the world. "It allows me to work with children or adults from all around the world, for I show them the picture and they know what I mean." Some of the jokes in the current exhibition, based on word games in the title, might require an understanding of German, but even in these the humor is simple and direct, once the joke is explained, and it is easy to see how the artist's mind works at capturing people's "smallest wishes" for such things as peace, or the enjoyment of the simple pleasures of life.

These tiny vignettes which zoom in on a single idea, with all the external detail ruthlessly cut away, is what makes Herman such an adept maker of icons.

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously