It's the middle of summer, I'm on a beautiful beach in the Ionian, and I can't see a single person. In the distance I can just about trace the path of the occasional car swinging down the mountain road like a slow-motion marble run, but that's it. I can't help giggling. I don't know what's more surprising - that there is 80km of "undiscovered" coast in southern Europe, or that it's in Albania.

Europe's Mediterranean coast has been done. Spain, France, Italy, Croatia. Even Montenegro, the world's newest country, was heaving when I visited this summer; the Rolling Stones played there a few days after I left. Much of Turkey's coast has been packaged, and don't get me started on Greece. Sure, you can get away from the hordes, but how far?

To reach the Albanian Riviera, one of the most spectacular strips of land in Europe, the small price to pay is a bit of a sore bum. The bus that plies the single road down the coast leaves at 6am from a car park in Tirana littered with imported German coaches, some of which still bear the name of their original destination - one claims to be headed for Wilhelmstrasse. I board mine and fall into a semi-sleep that is regularly interrupted by heavy lurches and bumps. Barely touched since the Italian army built it in the 40s, the coastal road is pockmarked and cracked.

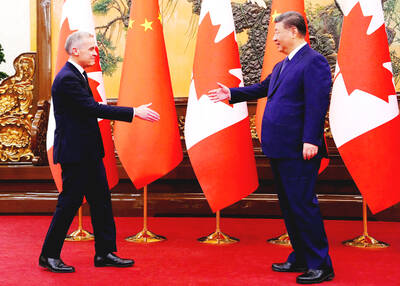

PHOTO: EPA

The state of the road is the main reason the Albanian Riviera - from Vlora to Saranda - has escaped large-scale tourist development. Even the Albanians tend not to bother with it, preferring resorts such as Durresi, easily reached from Tirana via a relatively bump-free motorway.

The Riviera begins at the peak of the 1,000m-high Llogara Pass, the road careering wildly down the slope. I jump off the bus in the tiny village of Dhermi, made up of about 100 terracotta-roofed houses scattered either side of the road, suspended halfway up the mountain range that continues south over the Greek border and beyond.

There is one hotel here, fronted by a boring-looking, low-rise mini-complex. The owner can tell I'm disappointed. He loads my backpack on to his truck, and drives me through dense olive groves and pine trees to the seafront, where I can see a collection of double-decker huts clad in pine. Much more like it. For US$40 a night, each hut has a double bed, a toilet and shower, and wardrobes. It isn't luxury, but it certainly isn't slumming it.

I count 14 people on the beach. Few foreign tourists come here, so it only fills up when the locals arrive at weekends. The coast stretches for a kilometer or so before curving out towards a shrubby headland. I feel blissfully alone. In the hotel's open-air restaurant, the waiter just about speaks Italian, which I just about understand, and I end up with a huge sea bass, Greek salad, and chips. I ask him where the fish came from, and he points to a man drinking by the bar. I retire to bed stuffed, where I can hear the waves brushing the shore, and a lone cricket up past its bedtime.

The next day I'm back on the bus for a 20-minute journey to the pebbly cove at Jaal, which again is virtually empty. I count 11 people. There are a few crumbling villas behind the beach, but accommodation options for visitors consist of a collection of beach huts at the base of the mountain. I meet a couple of German backpackers - the only non-Albanians I encounter - who plan to pitch their tent on the beach.

The Germans and I board the bus the next day, and the road brushes the sea for a few kilometers before arriving in Qeparo, where we sit outside a cafe as old men argue over a game of cards next to us. We have a lunch of fresh bread, creamy white cheese, sweet tomatoes, and oddly sized cucumbers; they are shaped so because everything in Albania is organic - fertilizers and pesticides are too expensive. And because of the unreliable roads, anything you eat on the Riviera is sure to be local.

The cafe's owner wanders over and we explain that we are looking for a hotel, but Alex says we can stay in his villa half way up the hill. He and his wife sleep in the back of the shop, a habit they acquired when riots swept the country in 1997 after the collapse of the pyramid investment schemes in which most of the country lost money.

By the close of the year the troubles had subsided, marking the end of seven years of political chaos triggered by the collapse of Albania's communist regime in 1990. Ten peaceful years later, Alex is renovating the upper story of his villa for his family to move back into, keeping the rooms on the ground floor for visitors.

He insists on driving us a few kilometers back up the coast to visit the deserted Ali Pasha fortress which juts out into in the Bay of Palermo. Back at the beach in Qeparo we sit under shelters made from branches and thatch looking out over the sea towards the peaks of Corfu, just visible in the distance.

The beach is dotted with Albania's ubiquitous bunkers, some of the estimated 700,000 concrete epitaphs to Enver Hoxha's paranoid rule that are scattered across the country. The bunkers, here playfully painted with pink and blue polka dots, were intended to protect the country against attack from the West, but these days they are more commonly used by naughty Albanians looking for a secluded spot to make love not war.

In the early evening we climb up to Qeparo's old town at the top of the mountain overlooking the sea. We can hear the murmurs of families tucked into the dozen or so white stone houses, and the clanging bells of a goatherd somewhere in the surrounding trees, but don't see a soul. Nighttime in the Riviera is a DIY affair. There are no snazzy restaurants or clubs, so you have to busk it with the locals. At Jaal we were invited to join a couple of youngsters on the beach for a bonfire. In Qeparo people congregated at Alex's cafe for cards, and lots of homemade rakia. In many eastern European countries people are understandably wary of tourists. But here they love anyone from abroad, simply because it's such a novelty. When we leave Qeparo the next day, with slightly heavy heads, Alex refuses to take any money from us.

It is the same ethic of hospitality that prompts goodbye hugs from two taxi drivers during my time in Albania, and that has fellow passengers helping me to order espressos and deliciously spicy offal broth during breaks on bus journeys. At Saranda, where the Riviera ends, an old man approaches me. Thamaj has the kind of magnanimous, round face that makes me instantly want him to be my granddad. Over coffee he tells of hiding Jews and fleeing Italians in his house during World War II, and giving shelter to a family of Kosovans after the horrors of the 1990s. The Albanians, I realize, have been good hosts for years.

From the cafe I watch the locals partake in that most Balkan of pastimes - wandering up and down in the early evening in your best outfit. Across the water, Corfu's coastline is ablaze. It's a chain of lights that runs, with occasional interruptions, until Europe merges with Asia. Around 160km north of where I'm sitting the chain picks up, and runs from the Adriatic all the way to the Algarve. In between is one of the most beautiful blips you'll ever come across, as long as a particular road remains particularly bumpy.

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

Britain’s Keir Starmer is the latest Western leader to thaw trade ties with China in a shift analysts say is driven by US tariff pressure and unease over US President Donald Trump’s volatile policy playbook. The prime minister’s Beijing visit this week to promote “pragmatic” co-operation comes on the heels of advances from the leaders of Canada, Ireland, France and Finland. Most were making the trip for the first time in years to refresh their partnership with the world’s second-largest economy. “There is a veritable race among European heads of government to meet with (Chinese leader) Xi Jinping (習近平),” said Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, director