Decades before it was given a name, Michelangelo Antonioni recognized the malady we now call attention deficit disorder. In his great 1960s films, L'Avventura, La Notte, Eclipse and Red Desert, but especially in L'Avventura, his masterpiece, it wasn't diagnosed as a chemical imbalance, but as a communicable social disease.

Spawned in a psychological petri dish in which idleness, boredom and dissatisfaction with the material rewards of life combined to create and spread a chronic, generalized, mild depression, it was an ailment peculiar to the upper middle class. What made audiences susceptible was the glamour that attached to it. As I watched the attractive aristocrats and climbers in his films mope through their empty lives, a part of me wanted to be just like those people: self-absorbed and miserable, perhaps, but also fashionable and sexy.

The ever-acute critic Pauline Kael recognized this contradiction in a famous essay, "Come-Dressed-as-the-Sick-Soul-of-Europe Parties," which aroused the ire of Antonioni devotees like me. More than four decades later, that contradiction remains unresolved in popular culture. Such is the power of film and television imagery that glamour and sex, no matter how tawdry or morally bankrupt, command our attention and whet our fantasies.

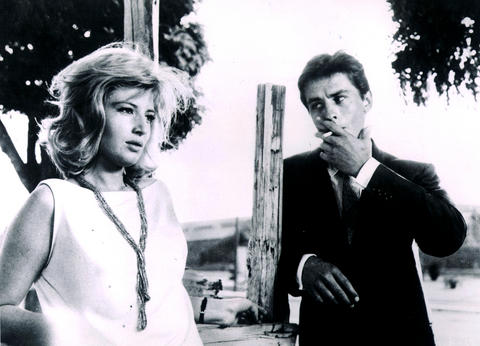

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Antonioni was the movies' first diagnostician of what back then was called alienation, anomie, angst and decadence. If his films had their silly side (the image of Jeanne Moreau and Marcello Mastroianni, grappling fully clothed in a sand trap in La Notte), they were also prophetic. Their melancholy poetry transmuted an overriding mood of self-pity into something deeper and closer to tragedy.

Antonioni's death on Monday, so close to Ingmar Bergman's, should give us pause. Their deaths bring down the final curtain on the high-modernist era of filmmaking, when a handful of directors were artistic gods accorded the respect and latitude of great painters or authors. Among the European masters of the 1960s, only Jean-Luc Godard, that most modern of modernists, remains.

For all their differences of temperament, Bergman and Antonioni were staunch moralists. If Bergman, the Scandinavian, was stern and austere, Antonioni, the Italian, was a sensuous aesthete who, when it suited him, resorted to painting nature the way he wanted it to look on the screen.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

If both had bleak apprehensions of the decline and fall of Western civilization in an increasingly secularized age, Antonioni's vision was more urbane and cosmopolitan. The final bleak street-corner montage in Eclipse is downright apocalyptic. In that movie, the third part of the trilogy that included L'Avventura and La Notte, the world is consumed with stock-market fever. Greed trumps love. Sound familiar?

The meticulous compositions in Antonioni's films depict a shiny but flimsy new world displacing an older and more solid one. Classic stone architecture constructed to last for centuries is contrasted with bright, new high-rise skyscrapers without character. Nuns in black habits rub shoulders with avaricious starlets and shallow socialites. The affluent new generation senses its own susceptibility to corruption. Sandro, the faithless male protagonist of L'Avventura, is a once-serious architect who is bitterly aware that he has sold out his talent.

L'Avventura and Federico Fellini's more flamboyant film La Dolce Vita, to which it was continually compared, tugged the European art film toward fashion. Together they inaugurated a vogue among trendy Americans to punctuate their conversations with "Ciao" (often uttered in a petulant, pseudo-Italian accent) instead of "Goodbye."

As the 1960s wore on, Antonioni increasingly succumbed to the taint of fashion. His most successful film, "Blowup," set in swinging London among photographers and models, was clever but shallow. Yet the protagonist's search for an elusive photographic truth was prescient.

Antonioni's vogue ended abruptly in 1970 with the critical and commercial failure of Zabriskie Point. At the time, that movie, his first feature made in the US, was widely misunderstood by fans longing to identify with its young lovers, who dabble in revolutionary politics. When no revolution occurred at the end, the audience that had lined up to see it (I saw its first two New York screenings) left frustrated. In hindsight, its climactic fantasy of a house repeatedly exploding (to the strains of Pink Floyd) predicted the imminent failure of that so-called revolution. The notion that it was just a fantasy was a message nobody wanted to hear.

But Antonioni's fashionableness shouldn't distract us from his accomplishment. He was a visionary whose portrayal of the failure of Eros in a hyper-eroticized climate addressed the modern world and its discontents in a new, intensely poetic cinematic language. Here was depicted for the first time on screen a world in which attention deficit disorder, and the uneasy sense of impermanence that goes with it, were already epidemic.

The startling conceptual coup of L'Avventura was the story's unexplained disappearance of a young woman, Anna, from a desolate, rocky island where she and a yachting party have landed. Even before the group, which includes Sandro, leaves the island without finding Anna, Sandro puts the moves on her best friend, Claudia (Monica Vitti). She resists his advances, but succumbs once they have returned to the mainland.

As the police search for Anna, the members of the party become distracted. Even for Claudia, the movie's conscience and Antonioni's alter ego, the urgency of finding Anna recedes in the heat of her new relationship. The cycle of betrayal culminates with the final scene: Claudia and Sandro are staying in a hotel, and she awakens to find him gone.

Venturing downstairs, she finds him sprawled on a couch with a prostitute, an exhibitionist with whom they had crossed paths earlier, as the prostitute created a paparazzi frenzy in a village they were passing through. This character may be the movies' very first "celebutante." Today she is everywhere.

May 11 to May 18 The original Taichung Railway Station was long thought to have been completely razed. Opening on May 15, 1905, the one-story wooden structure soon outgrew its purpose and was replaced in 1917 by a grandiose, Western-style station. During construction on the third-generation station in 2017, workers discovered the service pit for the original station’s locomotive depot. A year later, a small wooden building on site was determined by historians to be the first stationmaster’s office, built around 1908. With these findings, the Taichung Railway Station Cultural Park now boasts that it has

Wooden houses wedged between concrete, crumbling brick facades with roofs gaping to the sky, and tiled art deco buildings down narrow alleyways: Taichung Central District’s (中區) aging architecture reveals both the allure and reality of the old downtown. From Indigenous settlement to capital under Qing Dynasty rule through to Japanese colonization, Taichung’s Central District holds a long and layered history. The bygone beauty of its streets once earned it the nickname “Little Kyoto.” Since the late eighties, however, the shifting of economic and government centers westward signaled a gradual decline in the area’s evolving fortunes. With the regeneration of the once

The latest Formosa poll released at the end of last month shows confidence in President William Lai (賴清德) plunged 8.1 percent, while satisfaction with the Lai administration fared worse with a drop of 8.5 percent. Those lacking confidence in Lai jumped by 6 percent and dissatisfaction in his administration spiked up 6.7 percent. Confidence in Lai is still strong at 48.6 percent, compared to 43 percent lacking confidence — but this is his worst result overall since he took office. For the first time, dissatisfaction with his administration surpassed satisfaction, 47.3 to 47.1 percent. Though statistically a tie, for most

In February of this year the Taipei Times reported on the visit of Lienchiang County Commissioner Wang Chung-ming (王忠銘) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a delegation to a lantern festival in Fuzhou’s Mawei District in Fujian Province. “Today, Mawei and Matsu jointly marked the lantern festival,” Wang was quoted as saying, adding that both sides “being of one people,” is a cause for joy. Wang was passing around a common claim of officials of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the PRC’s allies and supporters in Taiwan — KMT and the Taiwan People’s Party — and elsewhere: Taiwan and