For the last 12 months, Ian Condry has been organizing a research project at MIT and Harvard on Cool Japan: Culture, Media, Technology. So on the surface he may appear to be one of those young academics who desperately wishes he was even younger, and seeks to redeem himself from the staid image university life often attracts by immersing himself in the culture of the markedly and trend-settingly young. But this would be to do him an injustice. This new book, his first, shows he has the merit of plowing his own furrow in research, of being able to read and speak Japanese fluently, and of being able to write clearly and forcefully about contemporary Asian life.

He spent 18 months on intensive research for the book between 1995 and 1997 and, on this and other visits to Tokyo and elsewhere, has probed pretty much every aspect of the Japanese popular music business. He's talked to rappers, DJs, record company executives and fans. He's even talked to Japanese rappers' parents, which must be something of a world first.

Japanese hip-hop, he relates, encountered considerable skepticism, even opposition, when it first emerged. Critics said the Japanese language was intrinsically alien to the conventions of rap lyrics, and in addition insisted the Japanese experience had nothing in common with that of Afro-Americans, the originators of hip-hop. Japanese rappers, these skeptics continued, were merely following an American fashion without being able to add anything of their own. Moreover, they were probably puppets dancing on the strings of record companies eager to emulate anything American and reap the profits of any new US musical style.

Condry, who has spent many long and smoky evenings in Japanese genba ("actual sites," or more simply clubs), not surprisingly disagrees. He's made friends with the stars and is clearly keen to see things from their perspective. One of his main arguments is that the music grew from the grass-roots upwards, and that recording executives were at first reluctant to take it seriously, or to believe Japanese youth would take to it in significantly profitable numbers.

At the heart of this book is the issue of globalization. Does the spread of hip-hop to Japan mean that everything American, from Wal-Mart to McDonald's, is destined to cover the globe with a uniform and stultifying sameness, or does the exchange of cultural influence quickly mutate into local variations that blend the imported with the inherited and create valuable new cross-bred "species" in innumerable locations?

Of course Japan, almost more than anywhere else, has for long been considered to have a veritable culture of imitation. Anyone my age remembers laughing at TV images of Beatles look-alikes peering out from under their long fringes and singing songs about UK locations such as Liverpool's Strawberry Fields or Penny Lane. Condry will have none of this. To him Japanese pop music, certainly of the hip-hop variety, is nothing if not distinctive and original. Far from copying American originals, it takes the form and develops it into local and often remarkable Japanese styles.

One of the most striking instances of this that Condry cites is a Japanese rap lyric composed by King Giddra in response to the 9/11 attacks. Of course radical, and especially anti-government, opinions are strongly characteristic of the genre in America, he admits, and the same is true in Japan. But where else, he wonders, would the video footage accompanying 9/11-related lyrics feature the post-atomic ruins of Hiroshima, with an image of the one emblematic building that remained in tact there duplicated to make it look like twin Hiroshima towers? The attacks on New York and Washington were terrible, it implies, but they were not the only examples of murderous assaults from the air.

Japanese rap is a thing out on its own, Condry insists, thinking for itself and more often than not making its own, Japan-related comments on global affairs.

That the artists involved have worked long and hard at their music, frequently doing daytime jobs to make ends meet, and most failing in the end to get a record contract, is essential to the picture the author paints. He's also keen to point out that they frequently take on the entrepreneurial side of things themselves when there's no one else to do it for them — renting rooms, charging admission and performing, and this in addition to recording their demo tapes, and even finished CDs, in the kitchens of their own, often tiny, apartments.

One musician/entrepreneur he got to know was Umedy, working part-time as a swimming coach to support his music, but then, after his rapping brother decided to go it alone, watching his group get dropped by both its record label and management company. The idea of two rapping brothers had, it seemed, been the only angle they'd felt able to promote. Umedy now works as the manager of Miss Monday, a singer he used to perform alongside.

Other topics covered include "sampling" (the use of other people's music, less common in Japan than in the US) and race as an issue in Japanese rap lyrics. Clearly the position of Afro-Americans in US society has no close parallel in Japan. Even so, words claiming the Ainu were Japan's original inhabitants, the first emperor came from Korea, and the Japanese were really aliens on their own soil were bleeped out from the pioneering first CD by artist ECD in 1992 as being too inflammatory.

The research for this book may appear to have been done several years ago, but the photos, many by the author himself, are often only a couple of months old. The cover picture, for instance, was taken this August — not bad considering publishers' usual schedules. Either way, the book attractively combines a careful combing through of other material on the topic with a reader-friendly amiability and marked loyalty to the artists interviewed. Hip-hop Japan may technically be an academic work in Asian anthropology, but non-academics interested in the subject can approach it and be fairly certain to find plenty of material in its pages to inform and even entertain them.

From the last quarter of 2001, research shows that real housing prices nearly tripled (before a 2012 law to enforce housing price registration, researchers tracked a few large real estate firms to estimate housing price behavior). Incomes have not kept pace, though this has not yet led to defaults. Instead, an increasing chunk of household income goes to mortgage payments. This suggests that even if incomes grow, the mortgage squeeze will still make voters feel like their paychecks won’t stretch to cover expenses. The housing price rises in the last two decades are now driving higher rents. The rental market

Fifty-five years ago, a .25-caliber Beretta fired in the revolving door of New York’s Plaza Hotel set Taiwan on an unexpected path to democracy. As Chinese military incursions intensify today, a new documentary, When the Spring Rain Falls (春雨424), revisits that 1970 assassination attempt on then-vice premier Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國). Director Sylvia Feng (馮賢賢) raises the question Taiwan faces under existential threat: “How do we safeguard our fragile democracy and precious freedom?” ASSASSINATION After its retreat to Taiwan in 1949, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) regime under Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) imposed a ruthless military rule, crushing democratic aspirations and kidnapping dissidents from

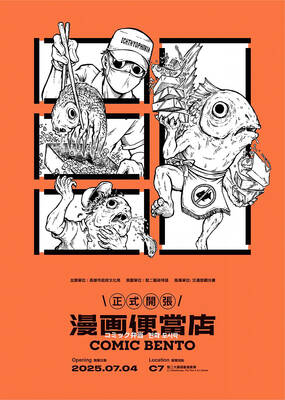

It looks like a restaurant — but it’s food for the mind. Kaohsiung’s Pier-2 Art Center is currently hosting Comic Bento (漫畫便當店), an immersive and quirky exhibition that spotlights Taiwanese comic and animation artists. The entire show is designed like a playful bento shop, where books, plushies and installations are laid out like food offerings — with a much deeper cultural bite. Visitors first enter what looks like a self-service restaurant. Comics, toys and merchandise are displayed buffet-style in trays typically used for lunch servings. Posters on the walls present each comic as a nutritional label for the stories and an ingredient

Fundamentally, this Saturday’s recall vote on 24 Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers is a democratic battle of wills between hardcore supporters of Taiwan sovereignty and the KMT incumbents’ core supporters. The recall campaigners have a key asset: clarity of purpose. Stripped to the core, their mission is to defend Taiwan’s sovereignty and democracy from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). They understand a basic truth, the CCP is — in their own words — at war with Taiwan and Western democracies. Their “unrestricted warfare” campaign to undermine and destroy Taiwan from within is explicit, while simultaneously conducting rehearsals almost daily for invasion,