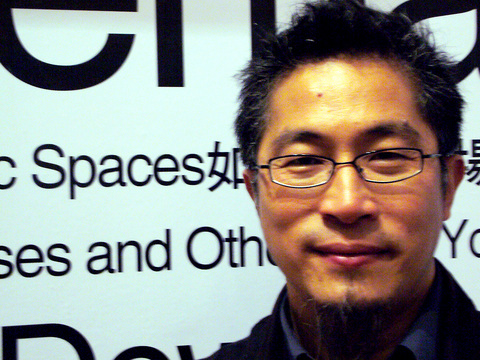

The common perception of a curator is a highly educated, distinguished man in a three-piece suit, smoking a pipe and leafing through old archive photos of ancient masters. Though Manray Hsu (徐文瑞) has a PhD in philosophy from Columbia University and wears a button down shirt, the independent curator who is based in Taipei and Berlin rarely spends time looking through boxes in the archives of old museums.

Like many contemporary artists, Hsu is concerned with how art affects our daily lives and creates a dialogue within the global and local contexts. This notion shapes his entire outlook on the art he chooses for exhibits, such as Naked Life, currently running at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei (MOCA).

Hsu differentiates between independent curators from institutional curators in two ways. First, he points out that independent curators don't work in or have an ongoing collaboration with any particular museum. Instead, they spend time moving from one museum or biennial to another picking and choosing projects that are most suited to their aesthetic vision. The corollary to this is that independent curators are also intellectually independent.

PHOTOS: NOAH BUCHAN, TAIPEI TIMES

"Freelance curators have [the] freedom … to develop ideas and projects in [their] own way. If you work in an institution you are more limited as to what you can do and what you can not do," he said.

Hsu also says that working independently enables the curator to collaborate closely with artists, which normally wouldn't be the case working inside an institution. "For me, independent means that I'm also more in contact with artists and those people in the field."

Collaborating with artists and working in the "field" has only become common in the past few decades. Until the 1970s, curators were predominately trained in art history, which had a tremendous influence on what hung on the walls of museums. "You still have an exhibition, but you don't rely on art history anymore. You can still do it, but art history is not the only framework. So you need to have people who can provide a smaller framework but still much bigger than the individual artwork. That's the curator's job. Framework providers," he said.

For Hsu, creating the proper framework for an exhibit necessarily involves a lot of travel because he seeks input from international artists.

"My job relies on my traveling. But an important part of this issue is contemporary culture, [which is] a global culture. There is no simple big narrative that can allow you to say, okay, I know the whole art world. So you need to have people from different parts of the world who can bring their perspective and their experience into the field. And normally these people are curators and theorists," he said.

Hsu's global perspective is readily apparent with the current lineup of artists exhibiting at MOCA who hail from as far a field as Iraq and as close to home as Japan. "[By] traveling, I've built my own conceptual network and this is another thing I bring into the art world," Hsu said.

According to Hsu, his extensive travels combined with a global outlook and a desire to directly cultivate talent fosters greater trust between the curator and artists because the latter are working directly with an individual, rather than an institution. The curator can then have a clearer picture of what the artist is trying to achieve because both sides are working together.

How art is classified according to culture is an important issue to Hsu who believes stereotypes of what a particular culture will produce need to be broken down.

One common notion that Hsu wants to rid the art world of is the idea that an artist's work is inseparable from their nationality.

"Just because this artist is from Iraq, then everything he does has to do with Iraq — this, for me, doesn't really make sense," he said. "When a Western artist exhibits in a professional exhibition, normally the exhibition will not mention the locality [where the ideas are formed] and I feel this is more questionable."

"Some artists are really conscious of their local history and some artists work on more formalistic issues inside art history so the idea of locality [is] relevant to artists in different ways, no matter if it is Western [or] Eastern."

The relevance of national history, borders and educational background is, Hsu believes, becoming less important. The question facing institutions is: can they react quickly enough?

Part of reacting to and participating in the social environment — whether global or local — involves formulating theories that help people understand the processes of change. For the biennial held earlier this year in Liverpool, Hsu developed an idea that shows how art can rejuvenate public spaces. Known as "archipuncture" it reveals how artwork in the public realm is connected to the energy flow of the city through its placement at particular points.

"Archipuncture for me ... provide[s] a perspective of how art can be related to the urban condition. Instead of just something that you look at … art also brings new energy flows to the place where it is exhibited. And this kind of new energy can be related to the health of the city," he said. Hsu makes it clear that this idea can be applied to any city throughout the world.

The exhibit at MOCA, in a similar manner to the 2006 Liverpool Biennial, involves both a global and local perspective. The title of the exhibit is meant to explore the contemporary mode of existence where anti-terrorism, border control and the gradual erosion of due process has stripped many citizens of their political rights and legal protections. The concepts embodied in Naked Life should have particular resonance for Taiwanese because of the country's forty-year history of martial law.

Naked Life is an attempt to raise awareness of global issues in a local context that moves beyond the cynicism of the polarizing politics that Hsu claims pervades Taiwan .

Following the rollercoaster ride of 2025, next year is already shaping up to be dramatic. The ongoing constitutional crises and the nine-in-one local elections are already dominating the landscape. The constitutional crises are the ones to lose sleep over. Though much business is still being conducted, crucial items such as next year’s budget, civil servant pensions and the proposed eight-year NT$1.25 trillion (approx US$40 billion) special defense budget are still being contested. There are, however, two glimmers of hope. One is that the legally contested move by five of the eight grand justices on the Constitutional Court’s ad hoc move

Stepping off the busy through-road at Yongan Market Station, lights flashing, horns honking, I turn down a small side street and into the warm embrace of my favorite hole-in-the-wall gem, the Hoi An Banh Mi shop (越南會安麵包), red flags and yellow lanterns waving outside. “Little sister, we were wondering where you’ve been, we haven’t seen you in ages!” the owners call out with a smile. It’s been seven days. The restaurant is run by Huang Jin-chuan (黃錦泉), who is married to a local, and her little sister Eva, who helps out on weekends, having also moved to New Taipei

The Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS) told legislators last week that because the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) are continuing to block next year’s budget from passing, the nation could lose 1.5 percent of its GDP growth next year. According to the DGBAS report, officials presented to the legislature, the 2026 budget proposal includes NT$299.2 billion in funding for new projects and funding increases for various government functions. This funding only becomes available when the legislature approves it. The DGBAS estimates that every NT$10 billion in government money not spent shaves 0.05 percent off

Dec. 29 to Jan. 4 Like the Taoist Baode Temple (保德宮) featured in last week’s column, there’s little at first glance to suggest that Taipei’s Independence Presbyterian Church in Xinbeitou (自立長老會新北投教會) has Indigenous roots. One hint is a small sign on the facade reading “Ketagalan Presbyterian Mission Association” — Ketagalan being an collective term for the Pingpu (plains Indigenous) groups who once inhabited much of northern Taiwan. Inside, a display on the back wall introduces the congregation’s founder Pan Shui-tu (潘水土), a member of the Pingpu settlement of Kipatauw, and provides information about the Ketagalan and their early involvement with Christianity. Most