In their crusade to take the pulse of contemporary art every two years, the curators of the Whitney Biennial often stray from the art world's beaten paths. But rarely have they strayed quite as far as this small farming town near Houston, along a road that leads to a beige-brick ranch house where a middle-aged man named Daniel Johnston lives with his elderly parents.

The road goes past a grain elevator and a Pentecostal church with a sign on the side announcing a "Holy Ghost Revival." If you drive too far, you end up at a trailer house with foil-covered windows and a rooster preening in the yard. The other day, when a reporter finally found Johnston's house and rang the bell at 1pm, his father, Bill, answered the door. "Dan's still asleep," he said. "I'll go get him up. He just got out of the hospital, you know."

Hospitals are familiar places for Daniel Johnston: the Austin State Hospital in Texas, several times; the Weston State Hospital in West Virginia, for long stretches; even Bellevue, where he ended up in 1988 not long after his arrest for scrawling Jesus fish inside the base of the Statue of Liberty.

But the most recent stay was different. Something, possibly the medication he uses to manage his serious bipolar disorder, caused him to develop a kidney infection and lapse into a comalike state for several weeks. In fact, on Nov. 30, when the Whitney announced its artists for this year's Biennial, Johnston was completely unaware that he had been chosen and that the prediction he had made to so many strangers over the years -- "Hi, my name is Daniel Johnston, and I'm going to be famous!" -- was coming true yet again.

It's not much of an exaggeration to say that next month is Daniel Johnston Month in New York. The Biennial begins March 2, with more than a dozen of Johnston's recent hallucinatory pen and Magic Marker drawings on view. On March 16, an exhibition of his artwork stretching back to the 1970s opens at the Clementine Gallery in Chelsea. And on the last day of the month, an award-winning documentary about him, The Devil and Daniel Johnston, will have its premiere in New York and Los Angeles.

Johnston has had this kind of news media moment before, as a musician. A certain substratum of indie fans reveres him for his sweet and frighteningly honest songs, most primitively self-recorded and sung in a voice like that of a heartsick Jerry Lewis. His music has been covered by, among others, Beck, Tom Waits and Wilco and has even inspired a contemporary ballet. But his visual artwork, produced with the same wild confessional intensity over the years -- there are easily thousands of drawings in existence -- has not been nearly as well known.

That is all about to change. So are the prices for his work, which Johnston used to give away or barter for comic books whenever he found a sympathetic store clerk behind the counter in Austin, his longtime home. Now, even some of his dashed-off drawings are selling for more than US$1,000 apiece. And with this sudden rise in his market, he finds himself in the middle of an art world tug-of-war, one that raises questions about the ethics of profiting from the work of a man mostly unable to manage his own affairs or sometimes even to get out of bed.

Madness, creativity and a lot of love

On one side of the fight are Johnston's father and brother, Dick, his managers and fierce protectors. On the other are two collectors: Jeff Brivic, a Los Angeles dealer who over the last five years has assembled probably the largest group of Johnston drawings, and Jeff Tartakov, Johnston's former longtime manager and an Austin music-scene fixture, who has amassed a few hundred. The Clementine Gallery on West 27th Street, which has courted all three parties and will sell work from each, recently entered the fray, trying to referee and establish a stable market for the work, which is now available mostly on the Internet.

The family accuses both Tartakov and Brivic of taking advantage of Johnston, contacting him without his family's knowledge and cajoling him into giving them his drawings for little or no money.

Both men deny exploiting the artist, and Tartakov -- portrayed in the documentary as a long-suffering Broadway Danny Rose, with most of his adult life invested in promoting Johnston -- said that were it not for his efforts over the past decade arranging exhibitions of the drawings, primarily in Europe, the work would not be worth as much as it is now. "I've always taken care of Daniel," Tartakov said. (He adds that besides paying Johnston for the work -- sometimes from US$50 to US$100 a drawing -- he has also split any profits he has made with Johnston, a claim that the family disputes.

At the center of all this frenzy is Johnston, 45, who seems almost completely oblivious to it. Asked recently what he thought of the Clementine Gallery and its owners -- Abby Messitte and Elizabeth Burke, two successful dealers who traveled to Waller (population 2,032) last September to meet him -- he said: "I have no idea. I've never heard of them."

Asked if he hoped to travel to New York to see his work at the Whitney, he shook his head resolutely: "I'm not in any condition to go overseas. It would wipe me out."

At his parents' house on a recent windy Texas day, he emerged from his room in dark blue warm-up pants and a burnt-orange warm-up jersey with a cigarette hole burned through the chest. It is still possible to see in him the thin, mischievous-looking musician whose picture showed up in Texas newspapers after he blustered his way onto an MTV program in 1985 and became a local hero in Austin. But he is much heavier now and looks much older than his mid-40s, with wiry graying hair and eyebrows like brambles. He is borderline diabetic and has pronounced tremors in both hands. His voice, while still strangely reedy, has been weathered by the Doral 100s he smokes incessantly.

He doesn't drive and has few chances to leave the house where he has lived for more than a decade with his father, 84, and his mother, Mabel, 83. So as he does with almost anyone who comes to see him, he suggested a trip into town. Over tacos and several glasses of compulsively sugared iced tea, he was by turns friendly, excited, petulant and distracted, sometimes all within a few minutes, as his friends warned he could be.

But in interviews over two days, he seemed acutely aware that he is viewed as an oddity, an overgrown child -- or as Feuerzeig puts it, "this pet of the underground." It is an image he seems simultaneously to hate and to revel in, using it to avoid any responsibilities or expectations. (At the dollar store in Waller, where Johnston asked to be taken, a reporter offered to help him pay for several bottles of diet cola, and Johnston suddenly yelled out: "Don't penny-ante me, man. I'm a rock star!" He laughed. The cashiers laughed, too, nervously.)

Pure expression

Johnston said he was not at all surprised that his artwork was finally becoming well known. "I never thought I'd make it with the music that much," he explained. "I thought I was going to be famous as a cartoonist. Even up to 1985, the year I got on MTV, I still thought that I was going to be a cartoonist."

He had wanted to be an artist since he was a child, worshiping comics legends like Jack Kirby with the same ardor that he worshiped Leonardo, Picasso and Dalm. His reasons for wanting to be an artist, he said, were no different from those of self-respecting bohemians throughout history. "I saw all the families and all those guys -- even my own father -- working in the factories and these places, working a real job, you know? And I said: `Hey, how am I going to get out of that? How can I escape that? I've got to be an artist. I've got to be famous."'

While he is often described as an outsider artist, the label doesn't really fit the way it does with, say, Henry Darger. Johnston studied art formally at Kent State, near where he was raised in West Virginia, and he is still well aware of his influences, which include Duchamp.

Occasionally, the work veers into the pornographic, though his parents -- members of the Church of Christ -- discourage this and fume when they hear about Tartakov's or Brivic's selling explicit drawings.

Philippe Vergne, deputy director of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and one of the Whitney Biennial's curators, said he had been a fan of Johnston's for years and rejected any notion that his work was simply a curiosity born of mental illness. "I see him as an artist on the periphery of the art world, but not an outsider artist," he said. "It's impressive when you see the consistency of the work."

Like many artists, insider or outsider, Johnston grows impatient when asked to explain his inspirations. "I just make stuff up -- because it's easy," he said, not looking up from his tacos. But unlike many artists, especially nowadays, he seems not to care how much his work is worth, as long as his basic needs are met: cigarettes, soda, CDs, DVDs and the pop-culture detritus that fill the overflowing studio he has set up in his parents' garage, a kind of artwork unto itself.

In fact, his father now buys nearly all his drawings. "I'll make a batch of drawings and I'll sell them to him," he explained, "and then we go to the dollar store and I buy my supply of Diet Coke with the money that he gives me for the drawings."

His father and brother then sell the artwork, mostly on the Internet, at www.hihowareyou.com, and have used income from the drawings and from his music to create a savings account for Johnston and to build a two-bedroom house for him -- now almost completed -- next to his parents'.

For years, Johnston's family was little concerned with the artwork, focusing more on the music. But his brother, Dick, a computer consultant who lives nearby, says that when it became clear that the drawings could help pay for Johnston's care, the family had to become more involved.

It entered into a relationship with the Clementine Gallery in part, he said, because the gallery agreed to split its profits not only from the work provided by the family but also from that supplied by Tartakov and Brivic. Johnston's father added that with more money coming in, the family had recently hired a lawyer to explore ways to protect their interests.

"The wolves are at the door, boy," he said.

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

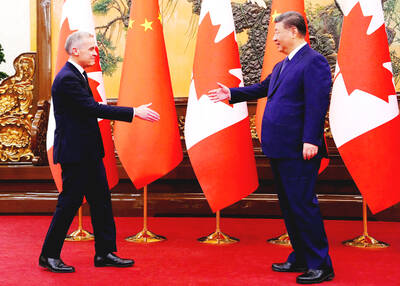

Britain’s Keir Starmer is the latest Western leader to thaw trade ties with China in a shift analysts say is driven by US tariff pressure and unease over US President Donald Trump’s volatile policy playbook. The prime minister’s Beijing visit this week to promote “pragmatic” co-operation comes on the heels of advances from the leaders of Canada, Ireland, France and Finland. Most were making the trip for the first time in years to refresh their partnership with the world’s second-largest economy. “There is a veritable race among European heads of government to meet with (Chinese leader) Xi Jinping (習近平),” said Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, director