Tattered book covers salvaged from the Iraqi Academy of Fine Arts and wax sketches of US bombs blowing up Baghdad are part of a rare exhibition of Iraqi artists in New York's SoHo gallery district.

Ashes to Art: The Iraqi Phoenix will be on display at the Pomegranate Gallery from today through Feb. 22.

The exhibit concentrates on subject matter from the most recent chapter of Iraq's history, beginning with the March 2003 bombing of Baghdad.

PHOTOS: AP

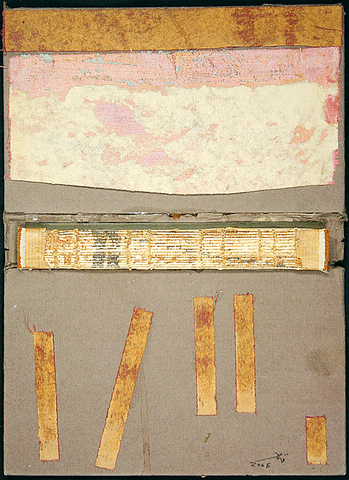

``The morning after that first sleepless night, I went to check on a place most dear to me, the Academy of Fine Arts,'' artist Qasim Sabti, who graduated from the academy in 1980, wrote in his statement for the exhibit.

He described entering the academy's library, which had been burned. Sabti turned books he refers to as ``survivors'' into collages by exposing and reapplying layers of their delicate bindings which are on show in the exhibit.

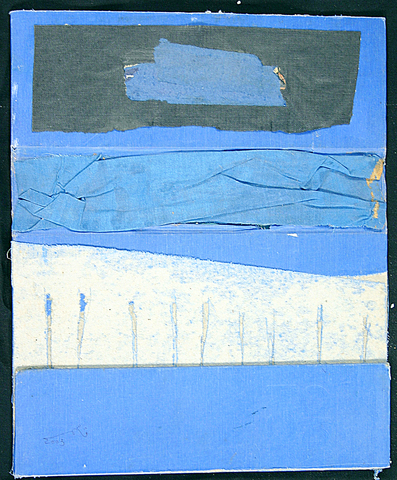

Hana Malallah, the lone woman among the 10 artists represented in the exhibit, submitted the painting The Looting of the Museum of Art, which she created on wood that she cut, burned and painted.

The exhibit's curator, Peter Hastings Falk, points out that a charred element exists in nearly all works in the exhibition. ``This is the aesthetic of the country,'' he said.

The idea for the exhibit began when Falk, whose expertise is in American art, became intrigued with artist Esam Pasha after reading about the artist in an August 2003 article, shortly after the US invasion of Iraq. ``He was painting over a mural of Saddam,'' Falk said.

Falk contacted the 29-year-old by e-mail and told him about his idea of organizing a show of Iraqi artists.

Pasha, a grandson of former Iraqi prime minister Nuri al-Said who was deposed and murdered in 1958, worked as a translator and language teacher, in addition to being a part of the Baghdad art scene. He helped Falk find an ethnically diverse group of Sunni, Shiite and Kurdish artists for the exhibit.

Artists in Iraq have long worked underground. Under Saddam's rule, artistic work was subject to official review. Regulations were relaxed in the 1990s, when officials were preoccupied by international sanctions, but the government began to tax the galleries. Some galleries went out of business while others just went underground.

``Art was growing its roots underneath the soil,'' Pasha said.

Sabti, the artist who salvaged books from the Academy of Fine Arts, founded the Hewar (Dialogue) Art Gallery in Baghdad in 1992, one of a few that would endure the renewed attention of Saddam. Sabti also serves as vice-president of the Iraqi Plastic Artists Society, an organization of artists with 1,780 members.

However, Iraqi artists couldn't show their work internationally without government approval, said Nada Shabout, an assistant pro-fessor specializing in contemporary Iraqi art at the University of North Texas. Uncensored work could only be found in places like Europe, where many exiled artists fled.

``The government had a strong monopoly over art,'' Shabout said in a phone interview.

Pasha recalled a time during Saddam's rule that he showed a friend a drawing he had done of an eagle falling. The friend suggested hiding the piece because the plummeting eagle ``might be interpreted as a symbol of the republic,'' he explained.

Pasha, a self-taught artist who perfected his English by watching American movies, had sold his art to UN aid workers during the 1990s embargo for around US$200 for a piece. In New York, one rendering in melted wax of the bombing of Baghdad is currently listed for US$2,400 on Falk's Web site.

Shabout, the art professor, curated an October exhibit of Iraqi contemporary art in Texas. She found visitors most surprised to find modern art existed in Iraq, and she partially blames the lack of exposure on regional stereotypes.

``It's easier to think of Iraq as the cradle of civilization,'' Shabout said.

Pasha plans to return to Baghdad eventually, and says he is optimistic about the outcome of the war. But when asked about the recent violence, including a suicide bombing that killed more than 130 people, Pasha pauses and strokes his beard. ``It does not look promising,'' he said.

On the Net:

Curator's site: www.falkart.com

May 18 to May 24 Pastor Yang Hsu’s (楊煦) congregation was shocked upon seeing the land he chose to build his orphanage. It was surrounded by mountains on three sides, and the only way to access it was to cross a river by foot. The soil was poor due to runoff, and large rocks strewn across the plot prevented much from growing. In addition, there was no running water or electricity. But it was all Yang could afford. He and his Indigenous Atayal wife Lin Feng-ying (林鳳英) had already been caring for 24 orphans in their home, and they were in

On May 2, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), at a meeting in support of Taipei city councilors at party headquarters, compared President William Lai (賴清德) to Hitler. Chu claimed that unlike any other democracy worldwide in history, no other leader was rooting out opposing parties like Lai and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). That his statements are wildly inaccurate was not the point. It was a rallying cry, not a history lesson. This was intentional to provoke the international diplomatic community into a response, which was promptly provided. Both the German and Israeli offices issued statements on Facebook

Even by the standards of Ukraine’s International Legion, which comprises volunteers from over 55 countries, Han has an unusual backstory. Born in Taichung, he grew up in Costa Rica — then one of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies — where a relative worked for the embassy. After attending an American international high school in San Jose, Costa Rica’s capital, Han — who prefers to use only his given name for OPSEC (operations security) reasons — moved to the US in his teens. He attended Penn State University before returning to Taiwan to work in the semiconductor industry in Kaohsiung, where he

Australia’s ABC last week published a piece on the recall campaign. The article emphasized the divisions in Taiwanese society and blamed the recall for worsening them. It quotes a supporter of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) as saying “I’m 43 years old, born and raised here, and I’ve never seen the country this divided in my entire life.” Apparently, as an adult, she slept through the post-election violence in 2000 and 2004 by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), the veiled coup threats by the military when Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) became president, the 2006 Red Shirt protests against him ginned up by