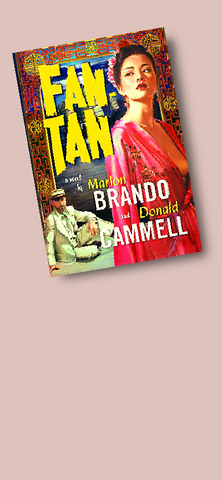

Did Marlon Brando really write a novel? The publishers would clearly like us to believe that he did. What this book contains, however, is something a little different from a tale of piracy on the South China Sea from the star of On the Waterfront, The Godfather and Apocalypse Now.

What appears to have happened is as follows. In the 1970s a project emerged for a film on such a subject. Brando is credited with the original idea, and the editor and completer of the book, David Thomson, points out that all his life the Hollywood legend had had a fascination with Asian women and women of part-Asian ancestry. He had even gone so far as to buy a Pacific atoll called Teti'aroa in the mid-1960s as a private retreat and hideaway.

The man Brando had in mind to make the film was Donald Cammell, the Edinburgh-born son of the heir to the Cammel Laird shipbuilding empire. He became a charismatic London figure during the late 1960s, mixing with such people as the Rolling Stones band-members, and briefly achieved fame in 1971 as director of the British cult movie Performance. Much later he was to conceive the idea for the film that others would eventually make as Pretty Woman.

But the proposed South China adventure movie never got off the ground. So, in the early 1980s, Cammell, who like so many of the 1960s hippie generation was by then wondering where exactly his life was heading, sat down and wrote the bulk of a novel on the story he and Brando had originally mapped out as a film treatment (i.e. proposal and synopsis) in 1979. The book was unfinished, but more or less in completed form as far as it went, that is up to, but not including, the final chapter. There was even a contract with the Pan publishing house, with an advance of US$50,000 paid to Cammell.

Then Brando announced he had no further interest in the idea. As the proposal to Pan had been in both their names, the project collapsed. Cammell stopped work, and in 1996, aged 62, shot himself in the head in front of his wife. It was an event that was viewed by some as emblematic of the era that had seen so much drug consumption, so much extravagant hedonism, but also much great music, plus highly unusual films such as Performance.

There was another aspect of the affair that was to prove significant. Cammell had married China Kong, "the exquisite child of of Anita Kong" (Thomson). And Anita King "had been Marlon's lover, on and off, over a long period".

So it was that in 2004 the widow China Kong Cammell approached the London literary agent Ed Victor with the manuscript of a novel. Thomson was assigned the task of editing it and writing the missing final chapter. This he has now done, and here it is with Brando's and Cammell's names on the front cover as the book's joint authors.

So -- did Marlon Brando have much of a hand in it? The idea certain seems to have been largely his, but the text was certainly written by Cammell alone, then tidied up by Thomson, and an ending supplied along the lines of the original joint 1979 film treatment.

Of course, now as 30 years ago, Brando's name was an essential prerequisite for a publishing contract. But the remarkable fact is that Fan-Tan reads exceptionally well. It's true it is somewhat self-conscious and pseudo-literary in places, a not uncommon fault with first books written over too long a period. But it's vigorous, historically very knowledgeable, ironic and engaging. The publishers call it "a rip-roaring adventure", and this is not an inappropriate claim.

Fan-Tan is set in and around Hong Kong in the 1920s. Annie Doultry (a man, named after the French writer Anatole France) lies in Hong Kong Island's Victoria prison, guilty of selling a small part of the consignment of arms he was carrying as a ship's captain. (By Hong Kong law it was legal to carry armaments through Hong Kong waters but not to sell them there). He watches Chinese prisoners perform the Hard Labor Number 1, a punishment apparently never given to Europeans at that time. They had to walk in a circle, picking up a 24-pound cannonball from one pyramid and depositing it on the next. Any failures were punished on the spot with the lash (the book is throughout notably anti-British).

He also watches, through his cell window, a man being hanged. This man, convicted of piracy, in his last moments of life denounces another prisoner as one of the biggest pirates on the South China coast. Doultry goes to the prison authorities and testifies that the man thus accused had been an honest cook in his employment. As a result the intended charges are dropped.

When he is released from jail, Doultry starts by getting his own back on the man who informed on him in the first place, and then, through contact with the man he has saved by his fictitious prison testimony, joins forces with the notorious and very real pirate, Madame Lai Choi San. Their escapades, culminating in the discovery of a fabulous cache of extremely

valuable pearls, combine with typhoons, Macau casinos (fan-tan is a Chinese gambling game where contestants bet on the number of buttons under an upturned cup) and triad initiations -- swallowing the heart of a beheaded cockerel, and so on -- to make the suitably exciting tale the publishers are now offering to the public.

And Marlon Brando? His 1994 memoir Songs My Mother Taught Me doesn't once mention Cammell. But in his later life his mind must have been taken up by many more worrying matters than an abandoned film project, notably the trial of his son Christian for murder.

Thomson, who appears to go out of his way to stress Brando's involvement throughout, does have one sardonic comment, however. "It is not an uncommon fantasy among Hollywood's great," he writes, "to think they could be writers if only they had the time, patience, a pen, or the spelling."

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not