There are two kinds of families in this village: the relatively rich, who live in tiled villas with air conditioning, and those who still hunt in the wooded hills with bow and arrow and send their sons off to become Buddhist monks when there are too many mouths to feed.

Such distinctions once lay in questions like who tills their paddies by hand under the broad, open skies in this rice-growing region of southwestern China, and who owns a water buffalo to perform the backbreaking work. But more and more these days, relative prosperity is tied to which families have daughters, many of whom go to Thailand and Malaysia to work in brothels.

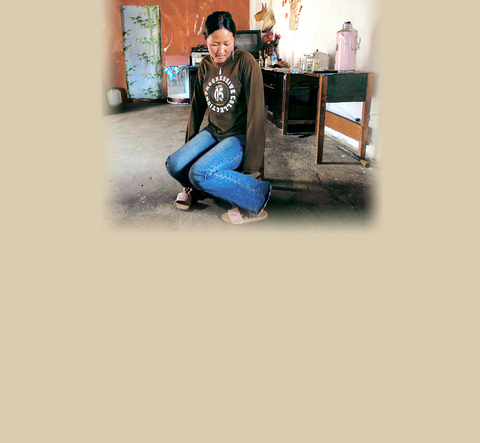

"If you don't go to Thailand and you are a young woman here, what can you do?" said Ye Xiang, 20, whose features still had the pudgy, unformed quality of a teenager's. "You plant and you harvest. But in Thailand and Malaysia, I heard it was pretty easy to earn money, so I went."

PHOTO: NY TIMES

At least 20 other young women from this tiny hamlet, which clings to a hillside just off a trunk road near the Mekong River, have headed off to foreign lands to work in the sex trade. "All of the girls would like to go, but some have to take care of their parents," Ye said.

In this regard, there is nothing peculiar about Langle, at least nothing peculiar for this part of Yunnan province, whose women are favorites in the brothel industry from Thailand, whose national language is related to their own dialect, all the way to Singapore.

Experts say that in some local villages the majority of women in their 20s work in this trade, leaving almost no family untouched, and the young men without mates. Not long ago, many of the recruits were kidnapped to become modern-day sex slaves, but these days the trade has become largely voluntary.

Ye told her story a bit haltingly, but without evident shame. Indeed, her father, a poor farmer, greeted visitors with glasses of hot water, in lieu of tea, and listened, along with a toothless aunt, as she spoke above the tinny noise of a cheap radio in their sparsely furnished one-room shack with a bare cement floor.

She told of her sacrifices -- from hiding in the baggage compartment of a bus to evade immigration police to the groping she endured in bars, where she lived not from a salary, but from patrons' "tips," the sex with strangers and the fear of AIDS. But what underpinned it all were dreams: of marriage to an overseas Chinese, or of at least putting away enough money to be able to return home in triumph.

Ye's first two years in Thailand had not yielded the success she had hoped for. She had earned only enough to eat and buy clothes, not leaving enough to help out her parents. But she was not discouraged, and neither were they. There had been a suitor, and she was eagerly preparing to go back.

"There's a guy in Malaysia, and he calls me every day," she announced proudly, showing off the cellphone he had bought her.

That dreams like these have come true in the past, however naive they may sound, is beyond dispute. This region is strewn with muddy villages crowded with tumbledown shacks, where a gleaming villa with gaudy gold-and-green gates and satellite dish emerges suddenly from the undifferentiated mass.

In some villages, indeed, the migrants' successes have been numerous enough to transform the hamlet itself, sprouting dazzling pockets of affluence that bear comparison with a Shanghai suburb. For this reason, unlike most of China where male children are highly prized, here it is the daughters who literally bring good fortune.

"These girls are motivated by their families and by their neighbors for one basic reason, because they are really poor," said a Beijing-based sociologist who has studied the migrant sex trade in Yunnan.

"The women come home and build big cement homes, and this is like an advertisement to others: This is an easy way to make money. Everyone knows what these women are doing in Thailand, but no one calls it prostitution, even local officials, who talk only of girls `working outside.'"

The sociologist, who asked not to be identified because the subject was so sensitive, said that disease was rampant among women who worked in the sex trade, a situation aggravated by the fact that public health care was denied to illegal foreign workers in Thailand. Despite this, the researcher said, no special efforts have been made to prevent the spread of AIDS in Yunnan by women returning from working in the sex trade in Thailand.

In Mengbin, a small village of the Dai minority, of Thai ethnicity, reached after several hours' drive, the sex trade had completely transformed the local life, starting with the sumptuous villas that had become the rule rather than the exception.

The practice of using beauty and sex to secure a livelihood had even worked its way into the home designs, with tiles depicting willowy, long-haired maidens interspersed here and there on the external walls and gates.

One rich matron, Dao Xiaoshan, proudly invited a visitor into her chateau-like home, with lace-covered couches, four chandeliers, a large, golden Buddhist altar and twin home-entertainment centers.

The secret of this bounty, she said lay in her husband's ownership of a coal mine. Others might conclude her luck was in having two daughters, 23 and 21 and beautiful, as seen in large, formal photographic portraits she had on display, including one showing a daughter dressed up in the gilt and violet regalia of a Thai princess.

"They have been able to work outside, but I've never asked them what they do," said Dao, who appeared to be in her 50s. Lately, she said, one daughter had found happiness with a rich Singaporean, the other with a wealthy Malaysian.

What about the young men here? "Dai boys can't marry Dai girls, because they all leave, and the ones who come back don't like the local boys anymore," Dao said, with a chuckle.

"Dai girls are beautiful, and they are very popular, but not all of them bring home money. Some of them don't know how to do anything but spend money and have a good time."

Sept.16 to Sept. 22 The “anti-communist train” with then-president Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石) face plastered on the engine puffed along the “sugar railway” (糖業鐵路) in May 1955, drawing enthusiastic crowds at 103 stops covering nearly 1,200km. An estimated 1.58 million spectators were treated to propaganda films, plays and received free sugar products. By this time, the state-run Taiwan Sugar Corporation (台糖, Taisugar) had managed to connect the previously separate east-west lines established by Japanese-era sugar factories, allowing the anti-communist train to travel easily from Taichung to Pingtung’s Donggang Township (東港). Last Sunday’s feature (Taiwan in Time: The sugar express) covered the inauguration of the

The corruption cases surrounding former Taipei Mayor and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) head Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) are just one item in the endless cycle of noise and fuss obscuring Taiwan’s deep and urgent structural and social problems. Even the case itself, as James Baron observed in an excellent piece at the Diplomat last week, is only one manifestation of the greater problem of deep-rooted corruption in land development. Last week the government announced a program to permit 25,000 foreign university students, primarily from the Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia, to work in Taiwan after graduation for 2-4 years. That number is a

This year’s Michelin Gourmand Bib sported 16 new entries in the 126-strong Taiwan directory. The fight for the best braised pork rice and the crispiest scallion pancake painstakingly continued, but what stood out in the lineup this year? Pang Taqueria (胖塔可利亞); Taiwan’s first Michelin-recommended Mexican restaurant. Chef Charles Chen (陳治宇) is a self-confessed Americophile, earning his chef whites at a fine-dining Latin-American fusion restaurant. But what makes this Xinyi (信義) spot stand head and shoulders above Taipei’s existing Mexican offerings? The authenticity. The produce. The care. AUTHENTIC EATS In my time on the island, I have caved too many times to

In a stark demonstration of how award-winning breakthroughs can come from the most unlikely directions, researchers have won an Ig Nobel prize for discovering that mammals can breathe through their anuses. After a series of tests on mice, rats and pigs, Japanese scientists found the animals absorb oxygen delivered through the rectum, work that underpins a clinical trial to see whether the procedure can treat respiratory failure. The team is among 10 recognized in this year’s Ig Nobel awards (see below for more), the irreverent accolades given for achievements that “first make people laugh, and then make them think.” They are not