When curators at the Ho Chuang-shih Calligraphy Society (

The traditionalists claim works that contain unrecognizable characters should not be classified as calligraphy. Such works should instead be described as abstract or calligraphy-influenced art. The modernists on the other hand argue that the rules the traditionalists abide by are outdated and should be reformulated in order to make calligraphy relevant to today's society.

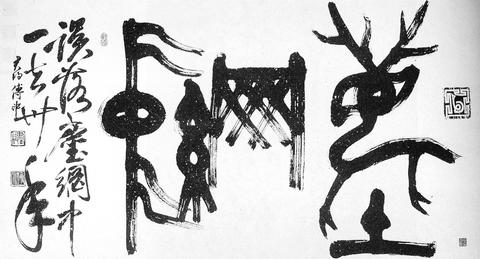

PHOTO COURTESY OF HO CHUANG-SHIH CALLIGRAPHY SOCIETY

Some of those responsible for challenging traditional calligraphic norms are members of Taiwan's only avant-garde calligraphy group, the Mochao or Ink Tide Society (

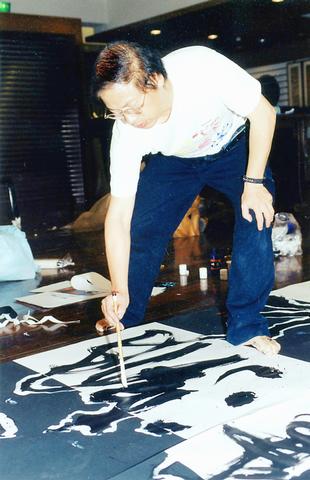

PHOTO COURTESY OF HSU YUNG-CHIN

The Ink Tide Society conveyed its message by incorporating calligraphy into installation art, turning characters upside down and inside out or writing in a variety of colors. The group's work was often so radical and contrary to calligraphic norms that many galleries remained apprehensive of exhibiting their works until the early 1990s.

"Many called it a betrayal of tradition. The traditionalists and critics who were brought up to believe that calligraphy can only be presented in one particular pattern were outraged," says Yang Tse-yun (

PHOTO COURTESY OF HSU YUNG-CHIN

"Of course, they had to be careful what they said, as the people they were criticizing to weren't unqualified. All the members [of the Ink Tide Society] were teaching art and traditional calligraphy full-time and were well known in the calligraphy community," Yang said, pointing out that the group was simply creating works that "were beyond the imagination of those calligraphers who persisted in following tradition."

Experimentation within the art of calligraphy is by no means new. During the 1940s, Japanese calligrapher Ueda Kuwabapo (

The acceptance of non-traditional calligraphy has taken longer in Taiwan. Works by contemporary calligraphers are closely scrutinized by conservatives, who want to ensure that calligraphy does not veer away from tradition.

Even before the current exhibition in Taipei opened, traditionalists and modernists had exchanged heated words. A work entitled Wei An Fu (

"The traditionalists called it a painting. They said the three characters `wei' (

"The excuse they gave as to why I had to re-do the work was rubbish. The rules as to what is and what isn't calligraphy are not written in stone; they are written by the traditionalists who are set in their ways and will never change. We are trying to bring calligraphy into the present day ... [We want to] make it accessible to the younger generations of people who haven't been taught about calligraphy, but who should still be able to enjoy it."

Making calligraphy more accessible to younger generations is also important to traditionalists. This is one point -- probably the only point -- on which the two camps agree, although they are poles apart on how this should be achieved.

"It was a nude. He tried to use the characters to create a nude and call it calligraphy," states Fu Shen (

"It wasn't calligraphy; it was an abstract painting. We've said that for a work to be called calligraphy it must contain readable characters and be two-dimensional. These rules are very clear, and Hsu broke them knowingly. I mean, when you're asked to play basketball you don't kick the ball. So why did he paint a picture?"

Hsu is adamant, however, that the work was never a painting. The fault, according to Hsu, lies with those who can't see the whole picture, rather than with him or his work.

"It boils down to the fact that after 25 years our group and the work we do has been noticed, and people are taking an interest. Which is more than can be said of traditional calligraphy. Okay, it is still very popular, but it has stagnated. It isn't going anywhere. It isn't changing with the times," said Hsu. "I created the Wei An Fu piece to be topical and up to date. What happens? A group of traditionalists who have no idea what contemporary calligraphy is come along and criticize it. They don't understand what we are trying to do with calligraphy. We've never criticized the art of calligraphy; we've simply been developing the content and the way it is presented."

All the same, Hsu resubmitted the work in a form that was acceptable to the exhibition's selection panel.

While remaining staunchly critical of contemporary calligraphy, Fu Shen believes that there is scope for development for the ancient art that does not transgress the basic rules of traditional calligraphy.

"There's nothing wrong with going beyond tradition. But you have to follow the rules. There's certainly nothing wrong with abstract works. Art is art after all. But such art is not [necessarily] calligraphy," explains Fu.

In 1999, Fu created his own contemporary piece. Titled The Speck of Dust (

"I chose to use characters from a poem written by Tao Yuan-ming (陶淵明). The characters are based on styles employed during the Chin Dynasty (晉, 365-420AD), but by presenting them as boldly as I have, the work looks very contemporary," states Fu. "It proves that calligraphers can still look to tradition for ideas and inspiration and still create a calligraphic work that is both recognizable and strikingly different."

Another avenue being explored by contemporary calligraphers is the incorporation of social or political criticism into their works. Two recent pieces by Ink Tide-member Lien Te-sen (

But according to Fu, while these works do take calligraphy to extremes, neither of them breaks any of the calligraphic rules adhered to by the traditionalists. The mediums might not be traditional -- Fo was created using plaster molded into the form of rose petals and Two Nations Two Systems with plastic topped pins -- but the characters are recognizable and the works both follow lines of traditional presentation.

Of course, not all works created from mediums other than ink can be called calligraphy. Hsu will be the first to admit that it will be some time before the traditionalists will allow that a piece he created in 1994 using a long piece of red cotton spread across a field constitutes calligraphy.

While the traditionalists and modernists will, no doubt, continue to disagree on calligraphic matters, the future of calligraphy looks set to be both colorful and distinctive as both sides push the ancient art to its limits and beyond.

Art Notes:

What: 25th anniversary exhibition of the Ink Tide Society (

Where: Ho Chuang-shih Calligraphy Society (

When: Until June 24

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them