Occam’s razor is a principle that says when something happens that can be explained in multiple ways, the simplest explanation is usually the right one. The same is true of solutions: The simplest, most straightforward solution is usually the best way to solve a problem.

In the US, social media giant Facebook has become a problem. It makes its money — US$23.3 billion last year adjusted earnings — by running roughshod over privacy concerns, selling users’ data to advertisers.

Along with Amazon, Apple and Google, it has “aggregated more economic value and influence than nearly any other commercial entity in history,” as marketing professor Scott Galloway wrote in Esquire earlier this year.

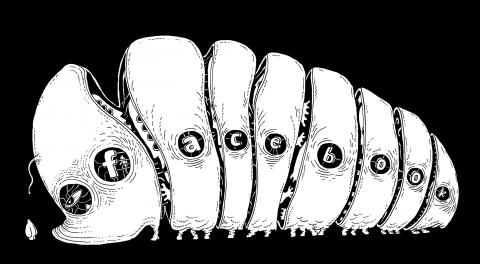

Illustration: Mountain People

It is a monopoly, having either bought or crushed most potential competitors.

It stifles innovation; as my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Noah Smith said, potential start-ups cannot get capital if venture capitalists think they might wind up as Facebook roadkill — such companies are said to be in Facebook’s “kill zone.”

Then there are the issues that have emerged since the 2016 US presidential election: how Facebook looked the other way as Russian interests spread disinformation; how it was slow to act as its platform was used to foment murder and rape in Myanmar; how it turned over user data to Cambridge Analytica, the sleazy political data firm working on US President Donald Trump’s campaign; and, in the most recent revelation, how it tried to discredit critics in the most odious of ways — by linking them to George Soros, the Jewish financier who has been demonized by the anti-Semitic right.

As more has emerged about Facebook’s business tactics, as well as its efforts to quash complaints, critics have come forth with lots of ideas about what to do about Facebook.

More than 30 US senators have cosponsored a bill that would force Facebook to abide by the same disclosure rules for political ads as television and newspapers. The New York Times called for congressional hearings. Antitrust economists have come up with a number of intriguing ideas to rein in Facebook.

However, the idea that makes the most sense — the one with the best chance to dilute Facebook’s power, spur innovation and insert competition into the social media industry — is the solution Tim Wu (吳修銘) proposed in his new book The Curse of Bigness. It is the Occam’s razor solution: Break Facebook up.

Wu is a Columbia University law professor best known for coining the phrase “net neutrality.” His short book is a plea to return to the day when antitrust enforcement meant something more than focusing on whether consumer prices might rise — which, he says, was most of the last century.

It has only been the past few decades that the “consumer welfare standard” first championed by Robert Bork became the sole prism though which antitrust regulators looked at mergers. That misguided focus has helped bring about a concentration of power not seen since the days of John D Rockefeller’s Standard Oil.

“Back then, the general counsel of Standard Oil made a speech in which he said that trying to prevent corporate concentration was like trying to prevent the rain from falling,” Wu told me the other day.

Monopolies were viewed as the natural course of capitalism, but former US president Theodore Roosevelt believed that no company should be more powerful than the federal government and that the drive to monopolize, as Wu writes, “seemed inevitably to come with its own morality.”

So in 1906, Roosevelt and his US Department of Justice brought an antitrust case against Standard Oil, won at trial and saw the verdict upheld by the US Supreme Court in 1912. Standard Oil was broken up into 34 parts.

When we spoke, Wu cited three other important antitrust cases where the goal was to break up an existing company: the AT&T lawsuit that resulted in the company spinning off the “Baby Bells” in 1984, the IBM suit that began in 1969 and the Microsoft trial in 1998.

It is true that the government failed to break up IBM or Microsoft. Even so, the mere fact of the lawsuits changed the behavior of the companies, allowing for innovation and competition that the two monopolies had prevented.

The software industry came about in no small part because IBM did not dare try to stop it; Google was able to grow knowing that Microsoft would not try to harm it the way it had Netscape.

As for AT&T and Standard Oil, can you imagine what the US economy would be like today if they had not been broken up? All four cases were critically important in allowing capitalism to flourish.

The point is, for most of the last century, antitrust regulators were unafraid to try to break up companies if they thought one had become too big or too powerful.

As Wu said, nowhere in the law is there even a mention of consumer welfare or the fear of higher prices.

On the contrary: In 1914, the US Congress passed the Clayton Act, which toughened the 1890 antitrust Sherman Act.

In so doing, “the nation had picked decentralization over concentration and competition over monopoly,” Wu wrote.

Today, the consumer welfare standard has given us any number of oligopolies — airlines, anyone? — that have demonstrably harmed consumers even if they have not caused prices to rise.

Antitrust regulators still demand divestitures before approving a merger — and sometimes oppose a merger entirely — but the idea of breaking up an existing company is no longer viewed as a realistic antitrust tool.

“It’s been stigmatized,” Wu told me.

It should not be. Let us return to Facebook. As I wrote in a column earlier this year, Facebook chief executive Mark Zuckerberg understood, earlier than others, that Instagram and WhatsApp might one day represent significant competition for Facebook, so in 2012 he bought Instagram and two years later he added WhatsApp.

Neither company has ever been integrated into Facebook; they stand as separate units with their own identities. They also have a less aggressively commercial ethos than Facebook and seem more concerned with privacy issues.

Or had, I should say: The founders of both companies are no longer there, tired of the pressure they felt from Facebook executives to act more like, well, Facebook.

With Facebook floundering, Instagram is now viewed internally as the growth driver. Many people who are tired of Facebook for one reason or another are turning to Instagram as their social media platform of choice. Many of them do not even know that Instagram is owned by Facebook.

However, the idea that your only option if you do not want to use Facebook is to use a company owned by Facebook is crazy. Competition would force Facebook to face its problems more squarely and it would give consumers options they do not now have.

The only way to get the “decentralization over concentration and competition over monopoly” that the US once valued is to break up Facebook. If Instagram, WhatsApp and Facebook were competitors, you likely would not need a raft of new regulations.

Competition itself would take care of most of Facebook’s problems. It would have to: If the company did not fix itself, customers would not stick around.

One of Wu’s core points is that there is nothing wrong with saying that too much industry concentration is something we should oppose — that even if consumer prices are not affected, there are a raft of negative consequences, both political and economic. Rarely are those negatives on such vivid display as they are right now at Facebook.

Nor is there anything wrong with calling for monopolistic companies to be broken up. Standard Oil was much more formidable than Facebook is today, but the government took it on, broke it up and made the economy healthier. Breaking up Facebook would be easy by comparison.

Joe Nocera is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He has written business columns for Esquire, GQ and the New York Times, and is the former editorial director of Fortune. He is coauthor of Indentured: The Inside Story of the Rebellion Against the NCAA.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion ofthe editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

The conflict in the Middle East has been disrupting financial markets, raising concerns about rising inflationary pressures and global economic growth. One market that some investors are particularly worried about has not been heavily covered in the news: the private credit market. Even before the joint US-Israeli attacks on Iran on Feb. 28, global capital markets had faced growing structural pressure — the deteriorating funding conditions in the private credit market. The private credit market is where companies borrow funds directly from nonbank financial institutions such as asset management companies, insurance companies and private lending platforms. Its popularity has risen since

The Donald Trump administration’s approach to China broadly, and to cross-Strait relations in particular, remains a conundrum. The 2025 US National Security Strategy prioritized the defense of Taiwan in a way that surprised some observers of the Trump administration: “Deterring a conflict over Taiwan, ideally by preserving military overmatch, is a priority.” Two months later, Taiwan went entirely unmentioned in the US National Defense Strategy, as did military overmatch vis-a-vis China, giving renewed cause for concern. How to interpret these varying statements remains an open question. In both documents, the Indo-Pacific is listed as a second priority behind homeland defense and

Every analyst watching Iran’s succession crisis is asking who would replace supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Yet, the real question is whether China has learned enough from the Persian Gulf to survive a war over Taiwan. Beijing purchases roughly 90 percent of Iran’s exported crude — some 1.61 million barrels per day last year — and holds a US$400 billion, 25-year cooperation agreement binding it to Tehran’s stability. However, this is not simply the story of a patron protecting an investment. China has spent years engineering a sanctions-evasion architecture that was never really about Iran — it was about Taiwan. The

In an op-ed published in Foreign Affairs on Tuesday, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairwoman Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) said that Taiwan should not have to choose between aligning with Beijing or Washington, and advocated for cooperation with Beijing under the so-called “1992 consensus” as a form of “strategic ambiguity.” However, Cheng has either misunderstood the geopolitical reality and chosen appeasement, or is trying to fool an international audience with her doublespeak; nonetheless, it risks sending the wrong message to Taiwan’s democratic allies and partners. Cheng stressed that “Taiwan does not have to choose,” as while Beijing and Washington compete, Taiwan is strongest when