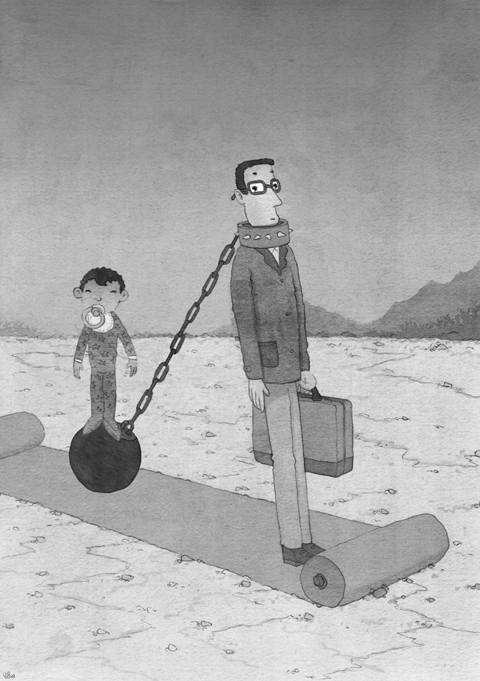

“New men” who try to combine paid work with playing a full role in their children’s lives aren’t having it all — just as “new women” discovered two decades ago.

That’s what a study published this week by the London-based Medical Research Council (MRC) seems to suggest. It found that one in five fathers have had at least one bout of depression by the time their eldest child reaches secondary school.

The MRC study is a landmark piece of research, drawing on the experience of 86,957 families. It discovered that 3 percent of fathers had been depressed in the first year of their child’s life, rising to 10 percent by the time their child was four, 16 percent by eight and 21 percent by 12. Mothers weren’t immune, of course — 13 percent had been depressed by the time of their child’s first birthday, 24 percent by their fourth, 33 percent by their eighth and 39 percent by their 12th — but it was the extent of “postnatal depression” (PND) in fathers that drew the biggest headlines.

“It is a much bigger problem than is generally recognized,” says Liz Wise, a postnatal depression counselor who advises the UK’s National Childbirth Trust on the issue. “We know it’s a problem for mothers — but there’s hardly any support for them and almost nothing for fathers.”

“People think it’s all about hormones in new mothers, but in fact hormones are only a small part of the problem. The other trigger-points can hit men just as easily as they hit women — things such as issues in their past life, for example, abuse, which come to the surface when a baby is born; feeling isolated; having had IVF [in vitro fertilization] treatment and being under financial pressure. The men I see with PND are more likely to have partners with PND,” she said.

“There will always be people who will pooh-pooh the idea of depression, in either mothers or fathers — but it’s definitely there and it’s definitely on the increase. The sad thing is that men are even less likely than women to come forward for help — and no one is looking out for them, so their problems go unnoticed,” she said.

“And what that means is that it’s the next generation who will be picking up the pieces — because parental depression has a huge knock-on effect,” she said.

ANDY MAXWELL, 40

A full-time father to Evie, five, and two-year-old Mia, whose wife Becky is expecting another baby in February.

I gave up work as a police officer to look after Evie — and that was at least partly because my wife was struggling with postnatal depression. When she was offered work that paid double what I could earn, it seemed an ideal option. But all that seems ironic now — because it was me who ended up depressed.

What made things particularly tough was that we moved to the countryside, far from my old life in London. Suddenly, I was on my own with a small child — often for days and weeks on end because Becky was working away. I had no network and no backup.

I can see now that my depression kicked in from the time Evie was a baby, but for many months I didn’t acknowledge it. Over time, it got worse — I never classed myself as suicidal, but there were times when I was on my own with Evie when I put an awful lot of thought into how I could kill myself.

I felt such an awful parent — I’d lie on the sofa drifting in and out of sleep, with the TV on for Evie. Even the wonderful playtimes we had together could change in an instant into chasms of despair.

I lost weight, going down from 75kg to a low of 52kg in December last year. I looked gaunt and yellow-skinned. By this stage we’d had another daughter — and it had just got too much. My wife was working all hours to meet the mortgage repayments, and I was in such a state I couldn’t even consider returning to work, either to contribute financially or just to get away from the kids. My self-esteem and self-confidence were shot through — I wouldn’t shave or shower for a week at a time, I couldn’t summon the energy to care about myself or my appearance.

Eventually, I went to the GP (general practitioner), and broke down when I admitted I thought I might be depressed. He assessed me and I was a pen stroke away from being admitted to hospital. He put me on antidepressants — but things didn’t change much, until a few months later I was diagnosed with a variety of other disorders, including Addison’s disease, that went hand-in-hand with my depression. I was admitted to hospital last year, put on the right medication and since then things have been better.

Having said that, my wife’s latest pregnancy was a shock and, if I’m honest, I’m not looking forward to another baby. But at least I know the challenges, and I know that if I need to get extra support, I have to do it sooner.

I think part of my problem has been that being a stay-at-home dad is still unusual — full-time parenting is women’s work. I don’t know how women put up with the lack of respect they get: I’ve had male friends talking as though it’s an easy choice. The support network that’s there for mothers just isn’t there for fathers. It’s taken a year for most mums at my daughter’s school even to acknowledge me when I drop Evie off.

MATT PADLEY, 33

A university research associate, he lives in Derbyshire with his wife Lesley, 34, Minnie-May, four, and Zebulun, 11 months.

Looking back, I think it all started with Minnie’s birth. Lesley had a tough time and an instrumental delivery; I found it really traumatic. But there was never anyone to talk to about it. It wasn’t fair to offload it all onto Lesley, and I don’t think she had any idea how I felt — after all, she’d been out of it during the delivery. I was the one who remembered everything that had happened.

I had a month off work, and that time was OK because I could concentrate on Minnie and Lesley. But when I went back to work, things started to really get me down. Everything was such a struggle — and it was so relentless. Minnie was waking all night so I was having to cope with no sleep, dragging myself into work feeling absolutely terrible, day after day. I’d had such high expectations of fatherhood — that I could be the provider, that I’d be cheerful, that I could support them both — and instead I was feeling angry and tired, and worrying about everything. Feeling I was failing made me even more depressed, so it was all a kind of cycle.

After Minnie, Lesley had two miscarriages and things got worse. No one talks about miscarriage, so you’re left bottling up all your feelings — even more so if you’re the father.

Eventually it got to the stage where I just wasn’t functioning. Things came to a head when I was given a really simple job to do at work — something I’d normally do in my sleep — and I just couldn’t do it. I went to see the GP, who asked if my sex life was OK and gave me the distinct impression that I simply needed to pull myself together. I left the doctor’s office feeling worse, because he seemed to have validated what a failure I was as a father.

He prescribed antidepressants but I didn’t want to take them. I went to see another doctor who was much more helpful, and now I’m seeing a counselor, and that helps a lot.

I can see that male postnatal depression is hard to understand, because men don’t have all those hormonal and body changes to cope with. But a lot of why women suffer is to do with the way having a baby turns your life upside-down — and men go through that too. But in our case it’s exacerbated by the feeling that you don’t have the right to feel like this, that you really should be able to cope, that people are depending on you.

At the moment I have good days and bad days. The good days outnumber the bad — Zeb is a much better sleeper than Minnie was — but there are still times when it all feels too much. I’m acutely aware of my limitations, and I don’t feel on top of things at all.

EDWARD DAVIES, 31

An editor, he lives in London with his wife Louisa, 32, Oliver, three, and 12-month-old Bertie.

I remember looking at Bertie when he was about three months and thinking I could just chuck him out of the window. It really was that bad; I had all the symptoms of postnatal depression. Everything had got much too much; I’d been rocking this child for what seemed like for ever and nothing I did seemed to make any difference, he was still screaming.

The problem is that you’ve no idea what a bombshell it’s going to be when you have children. Everything in your old life disappears: your career is different, your relationship is different, your social life is non-existent. I’ve always been sporty, played a lot of rugby, and that helps the way I feel psychologically — but once we had Oliver I couldn’t just bail out of the house to play rugby any more.

Especially in the early months, it all seems such a constant slog. You feel you’ve lost so much — even your wife, who is now someone’s mother and that’s more important. For me, the babies felt like big lumps who didn’t give much back. I felt I was on my own, with a big hole where my old life used to be.

Sleep deprivation is another killer. There’s a culture at the moment of everyone being very busy and feeling tired all the time, but you don’t know what tiredness is until you’ve got a three-month-old. It clouds everything; I couldn’t work properly, I couldn’t concentrate.

As a society, we pay lip service to shared parenting, but there’s no acknowledgement of what that really means — how it will affect fathers to have to hold down a job when they’ve got young children, how they might need time off or time out.

We need to start thinking about what being a father in 2010 is going to feel like — because it’s not going to be that poster of the fit-looking metrosexual guy caressing the baby, that’s for sure. What’s helped me, in the end, is getting involved with a charity called Insights for Life that runs breakfast clubs for fathers. Now, one day a week, I get together with a group of other dads on our way to work at 7am — and it really makes a huge difference to know I’m not alone, that there are other men going through this.

I can imagine there will be people who will read this and think, “Why should I pity him? A middle-class dad with healthy children — what’s he got to complain about?” But the fact is that all around us, dads are being criticized for running off and leaving their partners to bring up babies alone. And the thing is there are lots of men like me, trying our hardest — but when we’re up against it, who’s there for us?

They did it again. For the whole world to see: an image of a Taiwan flag crushed by an industrial press, and the horrifying warning that “it’s closer than you think.” All with the seal of authenticity that only a reputable international media outlet can give. The Economist turned what looks like a pastiche of a poster for a grim horror movie into a truth everyone can digest, accept, and use to support exactly the opinion China wants you to have: It is over and done, Taiwan is doomed. Four years after inaccurately naming Taiwan the most dangerous place on

Wherever one looks, the United States is ceding ground to China. From foreign aid to foreign trade, and from reorganizations to organizational guidance, the Trump administration has embarked on a stunning effort to hobble itself in grappling with what his own secretary of state calls “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted.” The problems start at the Department of State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has asserted that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power” and that the world has returned to multipolarity, with “multi-great powers in different parts of the

President William Lai (賴清德) recently attended an event in Taipei marking the end of World War II in Europe, emphasizing in his speech: “Using force to invade another country is an unjust act and will ultimately fail.” In just a few words, he captured the core values of the postwar international order and reminded us again: History is not just for reflection, but serves as a warning for the present. From a broad historical perspective, his statement carries weight. For centuries, international relations operated under the law of the jungle — where the strong dominated and the weak were constrained. That

On the eve of the 80th anniversary of Victory in Europe (VE) Day, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) made a statement that provoked unprecedented repudiations among the European diplomats in Taipei. Chu said during a KMT Central Standing Committee meeting that what President William Lai (賴清德) has been doing to the opposition is equivalent to what Adolf Hitler did in Nazi Germany, referencing ongoing investigations into the KMT’s alleged forgery of signatures used in recall petitions against Democratic Progressive Party legislators. In response, the German Institute Taipei posted a statement to express its “deep disappointment and concern”