Michael Winterbottom’s new film, The Killer Inside Me, has achieved a certain notoriety for its rapt attention to the murder of its female leads. It’s particularly the death of a prostitute, Joyce, played by Jessica Alba, which has divided viewers.

The murder hardly came as a surprise to me, given that when I went to see the film I had already read a couple of interviews with Winterbottom and a couple of assessments of the film, but even so, I was almost overwhelmed during the scene. It’s tough watching a woman whimpering “Why?” as her eye is punched out of place and her bones crunch.

I had been struck, in the articles on Winterbottom I had already read, by the fact that at first he didn’t seem to think there was anything particularly unusual about this avid lingering on a heroine’s physical destruction.

He said to one interviewer: “I’ve been a little surprised that people have found it so hard to watch the two main violent scenes ... I don’t think they are that visually graphic compared to other films.”

It’s true that his film’s explicit violence is not unique. Yes, if you go to see The Killer Inside Me you will be exposed to the spectacle of a woman being punched to death, with lingering shots of her bruised face. You will also see another heroine, Amy, played by Kate Hudson, killed in a similar way, and hear her struggling for breath as she slowly dies on the floor. Yet it is unlikely to be the first time that many viewers have sat through such scenes.

Violence has long been a staple of mainstream film-making, and filmgoers have been shuddering over the murders of women for generations, from Psycho to American Psycho. But over the past few years, violence against women, in particular, has become ever more forensically detailed. No wonder Winterbottom didn’t expect his film to cause outrage. It is not the first time this year that I have found myself feeling sickened by the flayed female flesh presented by a mainstream film.

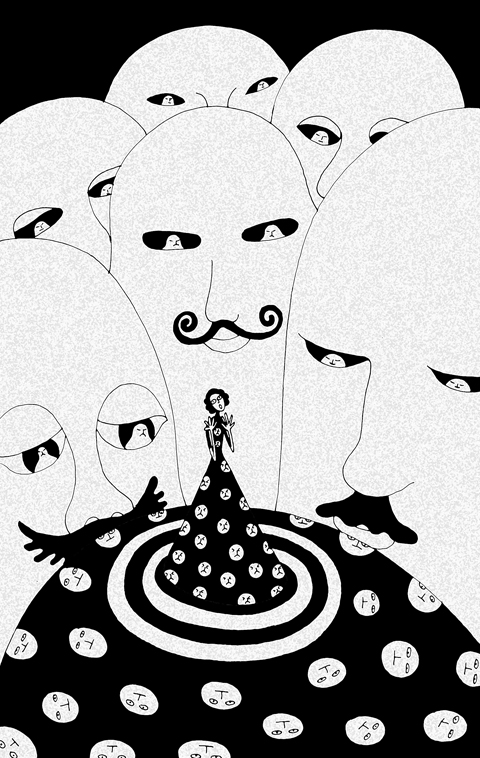

When I went to see The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, I found myself wondering why it is that our entertainment seems to rely so much on the fascinated depiction of women’s scarred and bruised bodies. The assumption is now — and it seems to be correct — that audiences are happy to watch their heroines being beaten and gagged, and to stare at explicitly rendered photographs of women cut and splayed and killed.

This is not just the staple of films that play to selected audiences. Mainstream television dramas now often choose to center on plots that rely on the depiction of women’s corpses and the process of their deaths. The most recent episode of Luther, the prime-time BBC police drama, started with a murderer leaning over the corpse of a woman and went on to present his previous and subsequent violence in detail. Television drama cannot go as far as cinema into the grosser particulars, but it shares much of the same aesthetic. This is not a marginal part of our entertainment.

Winterbottom is quick to remind his interviewers that his film does not condone the violence it shows. Indeed, those films and television dramas that center on violence against women usually foreground a straightforward moral framework in which murderers and rapists are seen as evil and perverted and must be punished.

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo goes even further, in providing a redemptive narrative by showing an active and intelligent female taking revenge on the men who kill or inflict violence on women. Yet it is still inescapable that so much of the emotional energy of these films and dramas center on women’s pain, and the extensive shots of corpses and battered flesh are a constant counterpoint to the condemnation of their treatment.

Perhaps in response to the criticism he has been receiving, Winterbottom has suggested that the more graphic such violence becomes, the more moral it is.

At the screening I went to, Winterbottom took questions after the film, and when I asked him why it was that his film chose to show such detailed violence, he replied: “It’s more moral to make it unwatchable.”

But this response does not bear much interrogation; what I find unwatchable the man beside me may find hilarious.

One writer told Winterbottom, in Interview magazine: “At my screening, I think I was smiling for most of the time.”

And when I thought back about The Killer Inside Me, the idea that it was providing a moral message about violence against women began to look absurd. The narrative may not explicitly condone murderous violence, but it suggests that it is the seedbed of true love. Not long into the movie, our hero goes to seek out the prostitute, Joyce. He is a baby-faced sheriff named Lou, played by Casey Affleck, and he goes to see her in order to warn her away from the town.

It’s all going badly between them until she loses her temper with him, and slaps him. Infuriated, he takes off his belt, pushes her on to a bed and beats her bare buttocks until she turns to him, embraces him and falls in love. This is, the film leaves us in no doubt, a real love, an undying love, an unconditional love that can survive even attempted murder.

This suggestion that violence will engender the most tender and lasting love is a facet of this film that has received less attention than the graphic nature of the murders, and yet it is more troubling. What’s more, it’s a repeated motif. Lou makes not one, but two women, fall unconditionally in love with him, and his relationship with the good girl, Amy, takes exactly the same form as his relationship with Joyce, the bad girl: he pushes her around, she adores him. Even at the moment of her death at his hands, she reaches piteously towards him.

For many years, feminists have been trying to unpick the myths that encourage men to believe that women love violent men, and yet in our mainstream culture now those myths are sloshing around, unquestioned. Some of the films and books that have repeated this yoking of love and violence in recent years could hardly be further from Winterbottom’s adults-only film.

The Twilight books and movies work in an entirely different register, and while there is a lot of fun for teenage girls in their dreamy world, many commentators have picked up on their troubling equation of violence and love. Throughout the books the heroine, Bella, is aware of the fact that her vampire lover can hardly control the violence that is an inextricable part of his desire for her. And after three long books, when they finally consummate their love, she wakes the next morning ready to take pride in her body’s extensive bruising.

To quote from the book: “I stared at my naked body in the full-length mirror ... There was a faint shadow across one of my cheekbones, and my lips were a little swollen, but other than that, my face was fine. The rest of me was decorated with patches of blue and purple ... Of course, these were just developing. I’d look even worse tomorrow.”

The Twilight books are fantasies that I would be reluctant to take too seriously, but nevertheless they reminded me how easy it is to slip into the mistaken belief that bruises are a sign of great love. Such beliefs may be held more widely than we like to imagine: I was struck by an interview with Alba in which she seemed to be buying into it on behalf of her character in The Killer Inside Me.

“It really is the most tragic of love stories ... she is always egging him on and provoking him,” Alba said.

I don’t want to shut down any kind of film-making, nor do I want to prevent storytellers from exploring the interconnections of love and death, which have underpinned much great art. But the ways that our current culture is exploring sex and violence feel increasingly claustrophobic. This is not just down to what we see, but what we don’t see.

The Killer Inside Me is adapted from a 1952 book written by Jim Thompson, that tells the tale of a psychopath from the psychopath’s point of view, and so it adopts an inevitably narrow and skewed viewpoint. Yet the way that the film denies much life to the women even before they are killed does not just reveal fidelity to the source material; it also brings into focus a characteristic of our contemporary culture. Although noir films of the past had any number of murdered women in them, in the ones that we remember, those women had character, had intelligence, had dreams of their own before those were snuffed out. But the heroines of this film have almost nothing except pretty underwear and bruised flesh.

And this is a real part of the problem; that while we are seeing so many women as victims in our films and our dramas, we seem to be seeing fewer women as active heroes. Why would talented and admired actors like Hudson and Alba take roles in which they are reduced to being only bodies, seen first sexually and then sadistically, if there were a full range of intriguing roles available to them?

Similarly, a drama series such as Luther comes at a time when there are few drama shows on prime-time television that show women being intelligent, complex and energetic. While there are any number of parts for women who are ready to play prostitutes and victims, there are few that are prepared to show them as active heroes.

Recently I sat down with a forty-something actress who is a British household name, and a female writer who has successfully written drama for British television. Both were separately lamenting the shift in television and film culture that was preventing them from developing the kind of strong and complicated roles that they believed were available to women in the past. It is in this context that the rise of drama and cinema that foregrounds women as victims has to be seen.

But maybe we should not be entirely downhearted. Although this particular film is so troubling in its depiction of women, when I look at its reception so far, I feel almost heartened. Many viewers are waking up to the fact that the repetition of certain patterns of violence is not the sign of an edgy dramatic vision, but rather the sign of a tedious old misogyny, and that it’s time for directors to find their thrills elsewhere.

As strategic tensions escalate across the vast Indo-Pacific region, Taiwan has emerged as more than a potential flashpoint. It is the fulcrum upon which the credibility of the evolving American-led strategy of integrated deterrence now rests. How the US and regional powers like Japan respond to Taiwan’s defense, and how credible the deterrent against Chinese aggression proves to be, will profoundly shape the Indo-Pacific security architecture for years to come. A successful defense of Taiwan through strengthened deterrence in the Indo-Pacific would enhance the credibility of the US-led alliance system and underpin America’s global preeminence, while a failure of integrated deterrence would

It is being said every second day: The ongoing recall campaign in Taiwan — where citizens are trying to collect enough signatures to trigger re-elections for a number of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators — is orchestrated by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), or even President William Lai (賴清德) himself. The KMT makes the claim, and foreign media and analysts repeat it. However, they never show any proof — because there is not any. It is alarming how easily academics, journalists and experts toss around claims that amount to accusing a democratic government of conspiracy — without a shred of evidence. These

The Executive Yuan recently revised a page of its Web site on ethnic groups in Taiwan, replacing the term “Han” (漢族) with “the rest of the population.” The page, which was updated on March 24, describes the composition of Taiwan’s registered households as indigenous (2.5 percent), foreign origin (1.2 percent) and the rest of the population (96.2 percent). The change was picked up by a social media user and amplified by local media, sparking heated discussion over the weekend. The pan-blue and pro-China camp called it a politically motivated desinicization attempt to obscure the Han Chinese ethnicity of most Taiwanese.

On Wednesday last week, the Rossiyskaya Gazeta published an article by Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) asserting the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) territorial claim over Taiwan effective 1945, predicated upon instruments such as the 1943 Cairo Declaration and the 1945 Potsdam Proclamation. The article further contended that this de jure and de facto status was subsequently reaffirmed by UN General Assembly Resolution 2758 of 1971. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs promptly issued a statement categorically repudiating these assertions. In addition to the reasons put forward by the ministry, I believe that China’s assertions are open to questions in international