In 1670, two men named William Penn and William Mead stood trial at the Old Bailey criminal court, charged with sedition after leading Quaker prayer services in a London street. The judge, Sir Samuel Starling — also London’s Lord Mayor — was so incensed when the jury returned a not-guilty verdict that he had them all imprisoned.

“You shall be locked up without meat, drink, fire and tobacco,” Starling is reported to have told the obstinate jury. “We will have a verdict, by the help of God, or you shall starve for it.”

Unbeknownst to Starling, the legacy of his tactics was to enshrine greater protection for the 12 men and women who decide a criminal trial. The independence of juries is often referred to as a “hallowed principle” of English justice — but this is now being threatened by a very modern phenomenon.

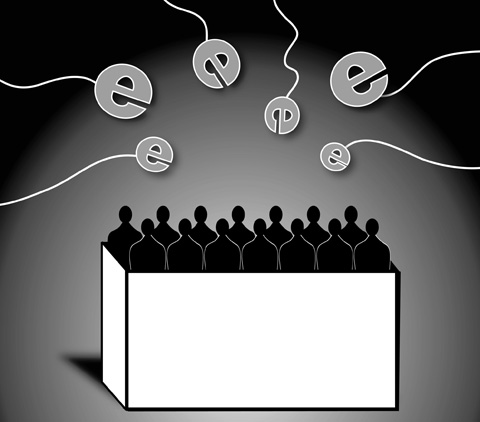

The problem, according to members of the legal profession, is that the Internet has entered the jury room. Instances of jurors using search engines such as Google and social networking sites such as Twitter and Facebook is compromising the strict rule that the only information available to them must have been carefully vetted by lawyers so as not to be “prejudicial,” or likely to unfairly influence the verdict.

All juries are segregated during each day’s hearings, entering and leaving court through private entrances and eating in a dining room designated only for juries sitting in that court. Yet even in the most high-profile cases, jurors usually go home at the end of each day, making their behavior outside the courtroom hard to monitor.

The attorney-general, judges and lawyers representing both prosecution and defense have all voiced their concerns.

“Let us be realistic and address the access jurors have to the Internet,” Lord Igor Judge, head of the judiciary in England and Wales, said recently. “Nowadays, judges [direct] the jury not to look at the Internet in connection with the trial. [But] inevitably, from time to time, an individual juror will disregard the direction and make his own private enquiries.”

The consequences of such inquiries can be serious. In 2005, a man named Adem Karakaya stood trial for repeatedly raping and assaulting a 14-year-old girl. The girl gave evidence against him and the jury found Karakaya guilty. After the verdict, however, a jury bailiff found Internet printouts in the jury room, including several about the difficulty of obtaining rape convictions. The case went to the court of appeal, where Judge and two other justices decided the conviction was unsafe. He was acquitted in a retrial.

“The introduction of extraneous material [into the jury room] contravened very well-established principles,” Judge said in his judgment. “The internet has many benefits and we do not mean to diminish its value ... It can, however, provide material which may influence a juror’s views. If used for research purposes during the trial, it can just as easily influence the juror’s mind as a discussion with a friend or neighbour.”

Since the Karakaya case, judges now give explicit instructions at the beginning of a trial that jurors should not look up anything connected with the case on the Internet — and, in the most serious cases, sometimes repeat this instruction at the end of each day’s proceedings. But lawyers say this is not always enough.

“It is becoming a big problem, particularly in cases involving disputed expert evidence,” says Eleanor Laws, a barrister at Six Pump court chambers who prosecuted Karakaya. “Or, more disastrously, if there has been sensational and prejudicial reporting of the case or an earlier related case, those details may still be found on the Internet. Unless a juror informs the court that another juror has conducted Internet research, or — as in Karakaya — the material is discovered, it is impossible to police.”

“This has been a problem for years,” another lawyer with extensive experience of criminal trials confirms. “I know one juror who said the first thing he did when he got home from court was to look the case up on the Internet.”

The high-profile trial last year of Steven Barker, Jason Owen and Tracey Connelly, the defendants ultimately convicted of causing the death of Peter Connelly (“Baby P”), was almost jeopardized by Internet sites that revealed their identities and campaigned for justice in the case. The authorities were forced to take unprecedented steps to restrict details available online, with the attorney-general, police, prosecutors and lawyers all working to ensure prejudicial information was removed from the Web.

“There are things we can do — it’s already happening,” British Attorney-General Patricia Scotland said during the Baby P trial. “We are taking down names and addresses from the Internet and we are working with service providers. People may think they can get away with breaching court orders, but I would say to those people: I wouldn’t want to mess around if I were them.”

Such efforts to police the information available does not always prevent jurors from doing private research, however. One juror recently approached a journalist at the end of a trial, asking which paper she wrote for and then complimenting her reporting as “a very good summary of events.” The juror admitted they had found out more important background by doing some surreptitious Googling.

And last year, a juror hearing a case about criminal property looked the defendant up online and discovered he had a previous conviction for money laundering. The defendant was found guilty, but had his conviction overturned because, the court of appeal said, the juror had failed to comply with the “spirit” of the judge’s instructions — and the rest of the jury had done the same by not reporting the wayward juror until three weeks later. Knowledge of the defendant’s previous convictions could have led to the jury forming an unfair “adverse view” of the defendant, the court said.

The concerns of lawyers are not limited to the UK. Research in New Zealand has found that jurors often seek out publicity about trials and conduct their own investigations. And in the US — where US President Barack Obama has just successfully deferred his call to serve on the jury at Cook County circuit court in southern Chicago — jurors have been discovered posting messages on Twitter including “my brain is dying from sitting in this juror room ... uugh!!!” and “loving this juror thing, its like law & order [a TV show]. I know what I want to be now when I grow up.”

“Just got done with day 2 of jury duty,” another tweet said. “Back at it tomorrow morning at 845 am ... who dunn it? I dunno.”

Yet another came as the verdict was being decided: “Deliberating!! I think I’ve reached my decision! But does everyone agree???”

In response, the US Supreme Court is considering the most explicit instructions yet banning jurors from using the Internet in conjunction with a case.

“I want to stress,” the proposed script says, “that this rule means you must not use electronic devices or computers to communicate about this case, including tweeting, texting, blogging, e-mailing, posting information on a website or chatroom, or any other means at all.”

But is it realistic for courts to place such expectations on people, particularly the young, who are less and less used to listening to information presented orally, preferring to look up anything they are vaguely curious about online? Furthermore, the difficulty of jurors presiding over complex fraud trials — following numeric evidence over a period that often stretches to months — is also cited as a reason that trial by jury is not up to the demands of modern criminal justice.

“It is perhaps unrealistic to expect that the judicial direction not to research the case on the Internet will always be followed,” Laws said. “You can warn the jury that they will be in contempt of court, but short of really heavy-handed threats that their computers could be seized — which will never happen — I’m not sure what else the court can do.”

This is a view endorsed by the UK’s lord chief justice: “We are hardly likely to welcome a suggestion that the technological equipment belonging to an individual juror should somehow be vetted. Such an intrusion would be entirely unacceptable.”

And yet the ever-more unrestrained behavior of jurors, compared with their more obedient counterparts of yesteryear, continues to cause concern. Last year, Guardian reporter Helen Pidd witnessed scenes she described as “extraordinary” when covering the libel battle between Express newspapers owner Richard Desmond and biographer Tom Bower.

“After delivering a majority verdict in favor of Bower, the jury mobbed him in the corridor outside the courtroom at the royal courts of justice,” Pidd said. “Bower lapped up the attention, thanked the jurors for delivering justice, and promised each a free copy of his next book if they e-mailed him.”

Another serious threat to the trial-by-jury system remains the intimidation of jurors — albeit no longer by judges such as Starling in 1670. Earlier this month, the first ever crown court trial in England and Wales to go ahead without a jury began to hear the case of a London-Heathrow airport robbery, after the previous trial had collapsed because of suspected jury tampering. The police said another jury trial could only have been held if up to 82 police officers were deployed to protect the jurors, at a cost of up to £6 million (US$9.6 million).

Yet this case has, in fact, led to a strong outpouring of support for the system of trial by jury, confirming its “hallowed” status in English criminal law. Instead, if jurors continue to tweet their views or Google the background of a case, the real threat to the future of juries may come from within.

Speaking at the Copenhagen Democracy Summit on May 13, former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) said that democracies must remain united and that “Taiwan’s security is essential to regional stability and to defending democratic values amid mounting authoritarianism.” Earlier that day, Tsai had met with a group of Danish parliamentarians led by Danish Parliament Speaker Pia Kjaersgaard, who has visited Taiwan many times, most recently in November last year, when she met with President William Lai (賴清德) at the Presidential Office. Kjaersgaard had told Lai: “I can assure you that ... you can count on us. You can count on our support

Denmark has consistently defended Greenland in light of US President Donald Trump’s interests and has provided unwavering support to Ukraine during its war with Russia. Denmark can be proud of its clear support for peoples’ democratic right to determine their own future. However, this democratic ideal completely falls apart when it comes to Taiwan — and it raises important questions about Denmark’s commitment to supporting democracies. Taiwan lives under daily military threats from China, which seeks to take over Taiwan, by force if necessary — an annexation that only a very small minority in Taiwan supports. Denmark has given China a

Many local news media over the past week have reported on Internet personality Holger Chen’s (陳之漢) first visit to China between Tuesday last week and yesterday, as remarks he made during a live stream have sparked wide discussions and strong criticism across the Taiwan Strait. Chen, better known as Kuan Chang (館長), is a former gang member turned fitness celebrity and businessman. He is known for his live streams, which are full of foul-mouthed and hypermasculine commentary. He had previously spoken out against the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and criticized Taiwanese who “enjoy the freedom in Taiwan, but want China’s money”

A high-school student surnamed Yang (楊) gained admissions to several prestigious medical schools recently. However, when Yang shared his “learning portfolio” on social media, he was caught exaggerating and even falsifying content, and his admissions were revoked. Now he has to take the “advanced subjects test” scheduled for next month. With his outstanding performance in the general scholastic ability test (GSAT), Yang successfully gained admissions to five prestigious medical schools. However, his university dreams have now been frustrated by the “flaws” in his learning portfolio. This is a wake-up call not only for students, but also teachers. Yang did make a big