In recent months, two big computer chipmakers slipped through Dresden’s fingers, challenging the notion that an area that likes to think of itself as “Silicon Saxony” can continue to churn out high-technology devices by the millions. But not every inhabitant of this picturesque city considers that a bad thing.

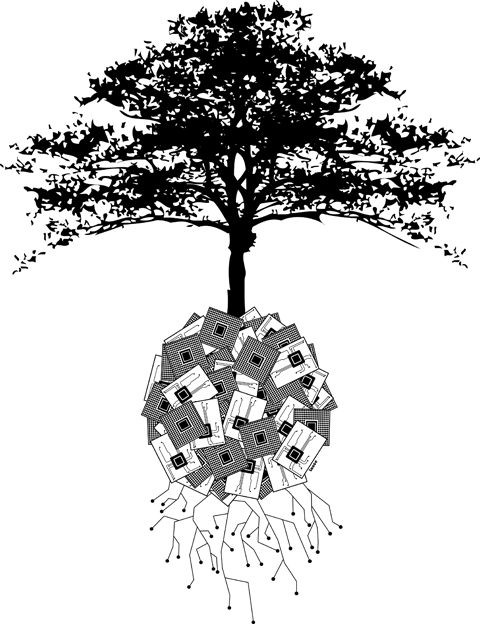

The loss has fired a debate over whether the future of Dresden, in what was once East Germany, should lie more in research and design rather than manufacturing, and few are more passionate about the intellectual side of the chipmaking business than the young entrepreneurs at Blue Wonder Communications. Barely four months old, the company is angling for a piece of the lucrative business in designing chips for the next generation of wireless technology.

Not one of its employees, almost all of them engineers, will actually manufacture anything.

“We need to put money in places that create knowledge, not things,” said Wolfram Drescher, one of two co-chief executives at the company. “If all we had were production and not knowledge, I’d be standing on the street, unemployed.”

The thought that traditional manufacturing should not necessarily be the indispensable foundation of the economy is heresy in Germany. But as China moves to supplant Germany as the world’s largest exporter of goods, the questions here over where to invest for the future go to the heart of an issue that Americans have faced for decades but that Germans are just beginning to confront.

The best examples of this tension come from Dresden. This year, the region’s largest private-sector employer — the chipmaker Qimonda — went bankrupt, while another, Global Foundries, broke ground in upstate New York on a new plant that Dresden had sought for itself.

DRESDEN LOSES OUT

Qimonda, a venture part-owned by memory chipmaker Infineon, turned to Thomas Jurk, Saxony’s economy minister, for help earlier this year. But when he traveled to Berlin to discuss the company’s situation with political leaders, he found that the chipmaker’s troubles were not their top priority. At the time, the government was focused on rescuing Opel, the main European subsidiary of the bankrupt General Motors.

“I heard first that they cared about Opel,” Jurk said, “and second that they cared about — Opel.”

Qimonda’s request for help ultimately proved too large for the state to save the company, and its insolvency cost, directly or indirectly, up to 6,000 jobs in the Dresden region.

Dresden started to become a center for high technology in 1999, when Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) built a chip fabrication plant to make microprocessors for personal computers. Suppliers of things like clean-room technology and masks sprang up around the region, and from 2002 to 2007, the number of people employed in the semiconductor industry more than doubled to 43,000.

This year, AMD split off its manufacturing business into Global Foundries, a joint venture with an investor from Abu Dhabi, and it is still a huge piece of the area’s economy. But Global Foundries, rather than expanding here, was drawn by a subsidy package of roughly US$1.2 billion to build its newest fabrication plant in Saratoga County, in upstate New York. It broke ground late last month.

Drescher says that Saxony needs to focus on what it can deliver — smart people — rather than play the subsidy game in a bid to sway decisions about where chipmakers will build plants.

Blue Wonder will design chips for the next generation of mobile phones, based on the emerging technical standard known as Long Term Evolution, or LTE. The company is in its infancy but the staff is not; most of them already know one another from working on another start-up together, a company that eventually became part of NXP, a spinoff of the Dutch electronics giant Philips, which closed its Dresden research center last year.

In truth, many were happy to go. Drescher recalls a smile creeping across a colleague’s face when the decision was announced.

“The fun factor is gone when your company is suddenly large,” Drescher said.

Barely six months later they were ensconced in a new office, on the third floor of a small office building that looks down on the Elbe River.

On a recent morning, Drescher, 43, clicked through a series of PowerPoint slides for Jurk.

“Knowledge beats production,” screamed one slide, while another drove the point home to the man who sometimes steers tax money toward local companies: “Saxony has to invest in development, less in production.”

Later, behind closed doors, Drescher delivered a pitch to Jurk, one his ministry is still mulling over. Blue Wonder needs test chips — products that incorporate its designs as prototypes — and is asking the state of Saxony to help finance them.

Blue Wonder, aware of the advantage of working with a German producer, wants to rely on the Global Foundries plant in Dresden, which is eager to diversify its roster of clients.

POLITICAL REALITIES

The idea reflects the political realities in Saxony, and indeed, Germany.

“I would say that the preference for manufacturing is at least as strong here as it is anywhere in Germany,” said Heinz Martin Esser, a managing director of Silicon Saxony, the industry’s local trade association.

It is, he added, “in the blood of the Saxons.”

The state worked hard early this decade to attract Porsche and BMW factories to Leipzig, its other major city after Dresden. And Chemnitz, once known as Karl-Marx-Stadt, has become a center for machine-tool makers.

Jurk, a 20-year veteran of Saxon politics, responded earlier this year to Qimonda’s request for help because he was sensitive to the fact that production facilities tended to employ more people than research labs.

Moreover, Qimonda supported a range of capital-intensive research efforts around Dresden.

No one knew that better than Juergen Ruestig, the scientific director of Namlab, a research center that was a partnership between Qimonda and a local university, which took over the insolvent company’s share of the venture.

Namlab’s research into nanotechnology will eventually help create more compact chip designs, and Ruestig had planned on sounding out what might interest the market through its partnership with Qimonda.

“Producers are your connection to the customer,” Ruestig said.

That’s a powerful argument, but Drescher counters that making things yourself is not as critical as it once was.

Qualcomm, one of the world’s largest makers of communications chips, owns nary a factory. And the place where the industry all began just lost its last semiconductor plant, without losing its dynamism, Drescher said.

“Silicon Valley isn’t a factory anymore,” he said. “It’s a think tank.”

On May 7, 1971, Henry Kissinger planned his first, ultra-secret mission to China and pondered whether it would be better to meet his Chinese interlocutors “in Pakistan where the Pakistanis would tape the meeting — or in China where the Chinese would do the taping.” After a flicker of thought, he decided to have the Chinese do all the tape recording, translating and transcribing. Fortuitously, historians have several thousand pages of verbatim texts of Dr. Kissinger’s negotiations with his Chinese counterparts. Paradoxically, behind the scenes, Chinese stenographers prepared verbatim English language typescripts faster than they could translate and type them

More than 30 years ago when I immigrated to the US, applied for citizenship and took the 100-question civics test, the one part of the naturalization process that left the deepest impression on me was one question on the N-400 form, which asked: “Have you ever been a member of, involved in or in any way associated with any communist or totalitarian party anywhere in the world?” Answering “yes” could lead to the rejection of your application. Some people might try their luck and lie, but if exposed, the consequences could be much worse — a person could be fined,

Xiaomi Corp founder Lei Jun (雷軍) on May 22 made a high-profile announcement, giving online viewers a sneak peek at the company’s first 3-nanometer mobile processor — the Xring O1 chip — and saying it is a breakthrough in China’s chip design history. Although Xiaomi might be capable of designing chips, it lacks the ability to manufacture them. No matter how beautifully planned the blueprints are, if they cannot be mass-produced, they are nothing more than drawings on paper. The truth is that China’s chipmaking efforts are still heavily reliant on the free world — particularly on Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing

Last week, Nvidia chief executive officer Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) unveiled the location of Nvidia’s new Taipei headquarters and announced plans to build the world’s first large-scale artificial intelligence (AI) supercomputer in Taiwan. In Taipei, Huang’s announcement was welcomed as a milestone for Taiwan’s tech industry. However, beneath the excitement lies a significant question: Can Taiwan’s electricity infrastructure, especially its renewable energy supply, keep up with growing demand from AI chipmaking? Despite its leadership in digital hardware, Taiwan lags behind in renewable energy adoption. Moreover, the electricity grid is already experiencing supply shortages. As Taiwan’s role in AI manufacturing expands, it is critical that