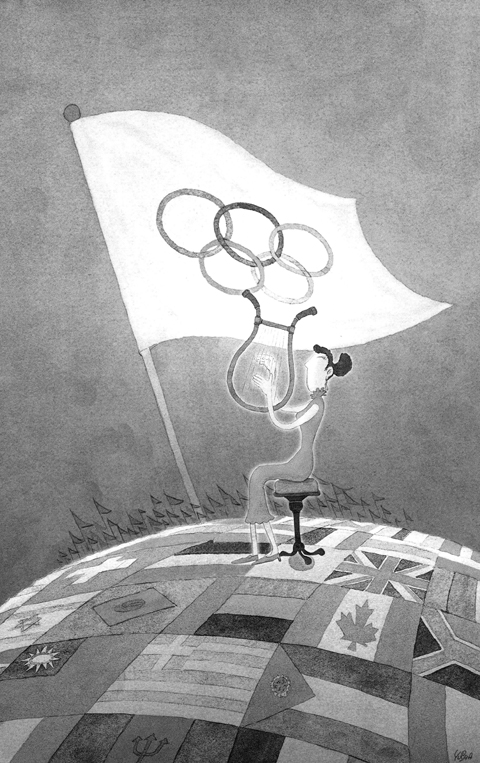

When the Beijing Olympics open in August, to a heady mixture of sporting celebration and political controversy, music will play a huge part in reinforcing the image and message of the Games. The opening will feature a program of world music, including a new work by Giorgio Moroder. Award ceremonies will feature national anthems, athletes will use music as a legal stimulant and motivational aid and for events such as synchronized swimming, music will of course be integral.

A cultural Olympiad for the 2012 London games is already the subject of much debate. But music has always played an important role in the event. In ancient Greece, singers received laurels for hymns composed for the various ceremonies, such as the elaborate sacrifice to Zeus. Athletes would be summoned by trumpets, while flautists accompanied the pentathlon. According to Baron Pierre de Coubertin, the Parisian aesthete who at the turn of the 20th century revived the games for a modern world: “The arts, in harmonious combination with sports, made the Olympic games great.”

Coubertin believed sport and the arts had become artificially separated. He wanted to integrate music into the competition itself. The 1912 Stockholm Olympics were thus the first to include a “pentathlon of the muses”: competitions for music, literature, painting, sculpture and architecture. Coubertin entered the literature contest under a pseudonym, winning gold with his inflated Ode to Sport — “O Sport, delight of the Gods, distillation of life!” Meanwhile, Italy’s now-forgotten Ricardo Barthelemy snatched the music gold with his Triumphal Olympic March. No silver or bronze medals were awarded.

This meanness on the part of the judges became a feature of the music Olympics over the coming years. Competitors were urged by Coubertin to “study the main rhythms of athletics.”

But few, it would seem, succeeded. Another problem was that composers of stature preferred to sit on the judging panel rather than risk denting their reputations by winning an ignominious bronze, should one be deemed worth giving. Worse still was the prospect of an “honorable mention.”

At the Paris Olympiad in 1924, a vast panel of 43 judges — including Vincent D’Indy, Igor Stravinsky, Bela Bartok and Mauric Ravel — failed to reach a decision. Four years later, a measly bronze was awarded to Denmark’s Rudolf Simonsen for his Hellas Symphony. In 1932, the single award of a silver medal damned with faint praise the most eminent of all Olympic music competitors, the Czech composer Josef Suk, for his patriotic march, Into a New Life.

At the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, new categories were introduced: orchestral compositions, instrumental music, solo and choral works. The judges, predominantly German, were particularly generous to native entrants. Werner Egk won gold for his orchestral work Olympische Festmusik, while all three medals in the choral category went to host nationals — thus proving the musical superiority of the master race.

The Nazis also pulled off a coup by commissioning Richard Strauss to write a work for the opening ceremony. After an oration by the Fuhrer, a cannon salute and the release of thousands of white pigeons, Strauss led the Berlin Philharmonic and the National Socialist Symphony Orchestra through his rousing Olympic Hymn.

He was far from enthusiastic about writing “sports music.”

In a letter to the writer Stefan Zweig, he said: “I am whiling away the dull days of advent by composing an Olympic Hymn for the plebs — I of all people, who despise sports.”

The 1948 games, hastily convened in war-torn London, opened with a performance of an ode by Roger Quilter and saw the Polish composer Zbigniew Turski take gold for his Olympic Symphony. Coubertin would have glowed at the presence of Micheline Ostermeyer, the remarkable Frenchwoman who won gold in both shot-put and discus, as well as bronze in the high jump. She celebrated her shot-put victory by giving an impromptu Beethoven recital at the French team headquarters.

“Sport,” she said, “taught me to relax; the piano gave me strong biceps and a sense of motion and rhythm.”

In 1950, she retired from athletics to resume her career as a concert pianist.

The 1948 games saw the end of the Olympic arts competitions, due to the growing difficulty of proving the amateur status of participants, but they had fulfilled Coubertin’s ambition of enshrining music in Olympic culture.

As Beijing will show, many types of music play a part — but it is classical music that has traditionally set the Olympics apart from what Coubertin called “plain sporting championships.”

John Williams, the US film score composer, wrote for the 1984, 1988 and 1996 Olympics.

He explained the attraction of the games thus: “The inspiration comes from the mythological idea we all seem to feel. It’s about deities and heroes that lived up in the mountain somewhere, that could do something we couldn’t do.”

Although Coubertin’s view of the Olympics now rings a little hollow, as drug-taking and commercialism threaten to consume today’s games, he would doubtless have approved of Williams’ lofty sentiments.

On May 7, 1971, Henry Kissinger planned his first, ultra-secret mission to China and pondered whether it would be better to meet his Chinese interlocutors “in Pakistan where the Pakistanis would tape the meeting — or in China where the Chinese would do the taping.” After a flicker of thought, he decided to have the Chinese do all the tape recording, translating and transcribing. Fortuitously, historians have several thousand pages of verbatim texts of Dr. Kissinger’s negotiations with his Chinese counterparts. Paradoxically, behind the scenes, Chinese stenographers prepared verbatim English language typescripts faster than they could translate and type them

More than 30 years ago when I immigrated to the US, applied for citizenship and took the 100-question civics test, the one part of the naturalization process that left the deepest impression on me was one question on the N-400 form, which asked: “Have you ever been a member of, involved in or in any way associated with any communist or totalitarian party anywhere in the world?” Answering “yes” could lead to the rejection of your application. Some people might try their luck and lie, but if exposed, the consequences could be much worse — a person could be fined,

Taiwan aims to elevate its strategic position in supply chains by becoming an artificial intelligence (AI) hub for Nvidia Corp, providing everything from advanced chips and components to servers, in an attempt to edge out its closest rival in the region, South Korea. Taiwan’s importance in the AI ecosystem was clearly reflected in three major announcements Nvidia made during this year’s Computex trade show in Taipei. First, the US company’s number of partners in Taiwan would surge to 122 this year, from 34 last year, according to a slide shown during CEO Jensen Huang’s (黃仁勳) keynote speech on Monday last week.

On May 13, the Legislative Yuan passed an amendment to Article 6 of the Nuclear Reactor Facilities Regulation Act (核子反應器設施管制法) that would extend the life of nuclear reactors from 40 to 60 years, thereby providing a legal basis for the extension or reactivation of nuclear power plants. On May 20, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) legislators used their numerical advantage to pass the TPP caucus’ proposal for a public referendum that would determine whether the Ma-anshan Nuclear Power Plant should resume operations, provided it is deemed safe by the authorities. The Central Election Commission (CEC) has