In the early 1940s, IBM president Thomas Watson reputedly said: "I think there is a world market for about five computers."

Watson's legendary misjudgment did not prove fatal to his company.

When businesses began buying mainframes in large numbers in the early 1950s, he quickly steered IBM into the new business. The proliferation of computers has, of course, accelerated ever since.

But Watson's prediction is suddenly coming back into vogue. In fact, some leading computer scientists believe that his seemingly ludicrous forecast may yet be proven correct.

Greg Papadopoulos, the chief technology officer at Sun Microsystems, recently declared on his blog: "The world needs only five computers" (tinyurl.com/yd5hs8). Yahoo's head researcher, Prabhakar Raghavan, seconds Papadopoulos's view.

In an interview in Business Week in December, he said: "In a sense, there are only five computers on Earth."

Most striking of all, some researchers at IBM believe that five computers may be four too many.

In a new paper, they describe how a single IBM supercomputer, which they codename Kittyhawk, may be all we need.

"One global-scale shared computer," they say, may be able to run "the entire internet."

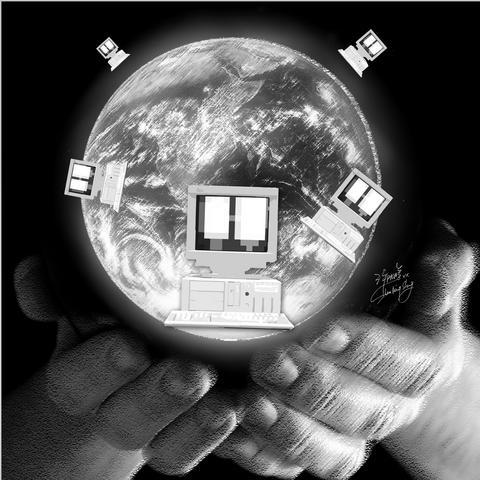

The idea isn't that we'll all end up using one big, central box to run our software and store our data. What these experts are saying is that the very nature of computing is changing.

As individual computers are wired together with the fiber-optic cables of the Internet, the boundaries between them blur. They start to act like a single machine, their chips and drives melding into a shared pool. Rather than writing software that runs on just one microprocessor inside one box, programmers can write code that runs simultaneously, or in parallel, on thousands of networked machines.

Such giant computing grids, explains Papadopoulos, "will comprise millions of processing, storage and networking elements, globally distributed into critical-mass clusters."

His point in calling them "computers," he says, "is that there will be some organization, a corporation or government, that will ultimately control" their construction and operation.

Their many pieces will work in harmony, like the components inside your PC.

This is not just a futuristic theory.

High-tech companies such as Google, Amazon, IBM and Deutsche Telekom are already building powerful computing grids that can do the work of thousands or even millions of individual servers and PCs. The computer scientist Danny Hillis, who is one of the pioneers of the parallel-processing method that the grids use, has called Google's global network of data centers "the biggest computer in the world."

It could be argued that the current consolidation of computing power is the fulfillment of the computer's destiny. In 1936, the great Cambridge mathematician Alan Turing laid out a theoretical blueprint for what he called a "universal computing machine" -- a blueprint that would take physical form in the electronic digital computer.

Turing showed that such a machine could be programmed to carry out any computing job. Given the right instructions and enough time, any computer would be able to replicate the functions of any other computer.

So, in theory, it has always been possible to imagine a single giant computer taking over the work of all the millions of little ones in operation today.

But until recently the idea has been firmly in the realm of science fiction.

There has never been a practical way to build a computing grid that would work fast enough and efficiently enough. Lots of little computers was the only way to go.

Now, thanks to the explosion in computing power and network bandwidth, the barriers to building a universal computer are falling. Very bright people can talk seriously about a world where there are only five computers -- or even just a single one -- that all of us share. It's not a world that Thomas Watson would recognize, even if it represents the future he accidentally foretold.

Nicholas Carr's new book is The Big Switch: Rewiring the World, from Edison to Google.

The Executive Yuan recently revised a page of its Web site on ethnic groups in Taiwan, replacing the term “Han” (漢族) with “the rest of the population.” The page, which was updated on March 24, describes the composition of Taiwan’s registered households as indigenous (2.5 percent), foreign origin (1.2 percent) and the rest of the population (96.2 percent). The change was picked up by a social media user and amplified by local media, sparking heated discussion over the weekend. The pan-blue and pro-China camp called it a politically motivated desinicization attempt to obscure the Han Chinese ethnicity of most Taiwanese.

On Wednesday last week, the Rossiyskaya Gazeta published an article by Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) asserting the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) territorial claim over Taiwan effective 1945, predicated upon instruments such as the 1943 Cairo Declaration and the 1945 Potsdam Proclamation. The article further contended that this de jure and de facto status was subsequently reaffirmed by UN General Assembly Resolution 2758 of 1971. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs promptly issued a statement categorically repudiating these assertions. In addition to the reasons put forward by the ministry, I believe that China’s assertions are open to questions in international

The Legislative Yuan passed an amendment on Friday last week to add four national holidays and make Workers’ Day a national holiday for all sectors — a move referred to as “four plus one.” The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), who used their combined legislative majority to push the bill through its third reading, claim the holidays were chosen based on their inherent significance and social relevance. However, in passing the amendment, they have stuck to the traditional mindset of taking a holiday just for the sake of it, failing to make good use of

As strategic tensions escalate across the vast Indo-Pacific region, Taiwan has emerged as more than a potential flashpoint. It is the fulcrum upon which the credibility of the evolving American-led strategy of integrated deterrence now rests. How the US and regional powers like Japan respond to Taiwan’s defense, and how credible the deterrent against Chinese aggression proves to be, will profoundly shape the Indo-Pacific security architecture for years to come. A successful defense of Taiwan through strengthened deterrence in the Indo-Pacific would enhance the credibility of the US-led alliance system and underpin America’s global preeminence, while a failure of integrated deterrence would