With 192 members and a mandate that covers everything from security to refugees to public health, the UN is the world's only global organization. But polls in the US show that two-thirds of Americans think the UN is doing a poor job, and many believe it was tarnished by corruption during the Iraq oil-for-food program under the late Iraqi president Saddam Hussein. Many also blame the UN for failing to solve the Middle East's myriad problems.

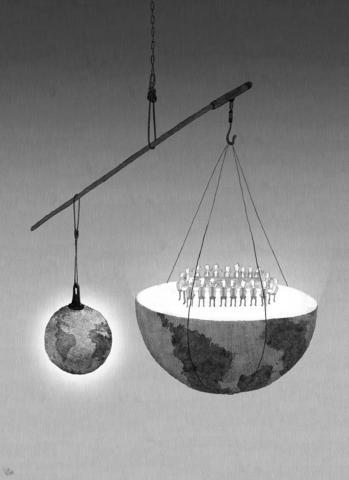

But such views reflect a misunderstanding of the UN's nature. The UN is more an instrument of its member states than an independent actor in world politics.

True, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon can make speeches, convene meetings and propose actions, but his role is more secretary than general. Sometimes likened to a "secular pope," the UN secretary-general can wield the soft power of persuasion but little hard economic or military power.

What hard power the UN has must be begged and borrowed from the member states. And when they cannot agree on a course of action, it is difficult for the organization to operate. As one wag has put it, "We have met the UN and it is us!" When blame is assigned, much of it belongs to the members.

Consider the oil-for-food program, which was designed by member states to provide relief to Iraqis hurt by sanctions against Saddam's regime. The secretariat did an inadequate job of monitoring the program and some corruption was involved. But the much larger sums that Saddam diverted for his own purposes reflected how the member governments designed the program and they chose to turn a blind eye to the abuse. Yet the program's problems are portrayed in the press as "the UN's fault.

The cost of the entire UN system is about US$20 billion, or less than the annual bonuses paid out in a good year on Wall Street. Of that sum, the secretariat in New York accounts for a mere 10 percent. Some universities have larger budgets.

Another US$7 billion supports UN peacekeeping forces in places like the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Lebanon, Haiti and the Balkans. The rest -- more than half -- is spent by the UN's specialized agencies, which are located around the world and often play an important role in managing global trade, development, health, and humanitarian assistance.

For example, the UN High Commission for Refugees helps to alleviate the problems of displaced persons, the WHO supports the public health information systems that are crucial for dealing with threats from pandemics like avian flu and the World Food Program provides assistance to malnourished children. The UN does not have the resources to solve the problems in new areas like AIDS or global climate change, but it can play an important convening role in galvanizing the actions of governments.

Even in the area of security, the UN retains an important role. The original 1945 concept of collective security, by which states would band together to deter and punish aggressors, failed because the Soviet Union and the West were at loggerheads during the Cold War.

For a brief moment after a broad coalition of countries acted together to force Saddam out of Kuwait in 1991, it looked like the original concept of collective security would become "a new world order." Such hopes were short-lived. Consensus within the UN proved unachievable on both Kosovo in 1999 and Iraq in 2003.

Skeptics concluded that the UN had become irrelevant for security questions. Yet last year, when Israel and Hezbollah fought to a stalemate in Lebanon, states were only too happy to turn to a UN peacekeeping force.

Ironically, peacekeeping was not specified in the original charter. It was invented by the second secretary-general, Dag Hammarskjold, and Canadian foreign minister Lester Pearson after Britain and France invaded Egypt in the Suez crisis of 1956. Since then, UN peacekeeping forces have been deployed more than 60 times.

There are now roughly 100,000 troops from various countries wearing UN blue helmets around the world. Peacekeeping has had its ups and downs. Bosnia and Rwanda were failures in the 1990s, and then secretary-general Kofi Annan proposed reforms to deal with genocide and mass killings.

In September 2005, the states in the UN General Assembly accepted the existence of a "responsibility to protect" vulnerable peoples. In other words, governments could no longer treat their citizens however they wanted.

A new Peacebuilding Commission was also created to coordinate actions that could help prevent a recurrence of genocidal acts. In East Timor, for example, the UN proved vital in the transition to independence, and it is now working out plans for the governments of Burundi and Sierra Leone. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, peacekeeping forces have not been able to curb all violence, but they have helped to save lives. The current test case is the situation in Sudan's Darfur region, where diplomats are trying to establish a joint peacekeeping force under the UN and the African Union.

In the poisonous political atmosphere that has bedeviled the UN after the Iraq War, widespread disillusionment is not surprising. Ban has a tough job. But, rather than calling the UN into question, states are likely to find that they need such a global instrument, with its unique convening and legitimizing powers.

While the UN system is far from perfect, the world would be a poorer and more disorderly place without it.

Joseph Nye is a professor at Harvard University.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

President William Lai (賴清德) recently attended an event in Taipei marking the end of World War II in Europe, emphasizing in his speech: “Using force to invade another country is an unjust act and will ultimately fail.” In just a few words, he captured the core values of the postwar international order and reminded us again: History is not just for reflection, but serves as a warning for the present. From a broad historical perspective, his statement carries weight. For centuries, international relations operated under the law of the jungle — where the strong dominated and the weak were constrained. That

The Executive Yuan recently revised a page of its Web site on ethnic groups in Taiwan, replacing the term “Han” (漢族) with “the rest of the population.” The page, which was updated on March 24, describes the composition of Taiwan’s registered households as indigenous (2.5 percent), foreign origin (1.2 percent) and the rest of the population (96.2 percent). The change was picked up by a social media user and amplified by local media, sparking heated discussion over the weekend. The pan-blue and pro-China camp called it a politically motivated desinicization attempt to obscure the Han Chinese ethnicity of most Taiwanese.

On Wednesday last week, the Rossiyskaya Gazeta published an article by Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) asserting the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) territorial claim over Taiwan effective 1945, predicated upon instruments such as the 1943 Cairo Declaration and the 1945 Potsdam Proclamation. The article further contended that this de jure and de facto status was subsequently reaffirmed by UN General Assembly Resolution 2758 of 1971. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs promptly issued a statement categorically repudiating these assertions. In addition to the reasons put forward by the ministry, I believe that China’s assertions are open to questions in international

The Legislative Yuan passed an amendment on Friday last week to add four national holidays and make Workers’ Day a national holiday for all sectors — a move referred to as “four plus one.” The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), who used their combined legislative majority to push the bill through its third reading, claim the holidays were chosen based on their inherent significance and social relevance. However, in passing the amendment, they have stuck to the traditional mindset of taking a holiday just for the sake of it, failing to make good use of