Sept. 11, 2001, is one of those dates that mark a transformation in world politics. Just as the fall of the Berlin Wall on Nov. 9, 1989, signified the Cold War's end, al-Qaeda's attack on the US opened a new epoch. A non-governmental group killed more people in the US that day than the government of Japan did with its surprise attack on another transformative date, December 7, 1941.

While the jihad terrorist movement had been growing for a decade, Sept. 11 was the turning point. Five years into this new era, how should we characterize it?

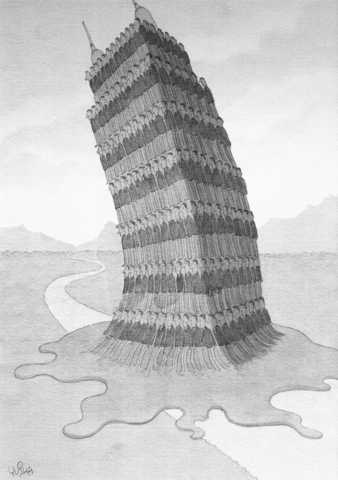

Some believe that Sept. 11 ushered in a "clash of civilizations" between Islam and the West. Indeed, that is probably what Osama bin Laden had in mind. Terrorism is a form of theater. Extremists kill innocent people in order to dramatize their message in a way that shocks and horrifies their intended audience.

They also rely on what some have called "jujitsu politics," in which a smaller fighter uses the strength of the larger opponent to defeat him.

In that sense, bin Laden hoped that the US would be lured into a bloody war in Afghanistan, similar to the Soviet intervention two decades earlier, which had created such a fertile recruiting ground for those bent on terrorism.

But the US used a modest amount of force to remove the Taliban government, avoided disproportionate civilian casualties, and was able to create an indigenous political framework.

While far from perfect, the first round in the fight went to the US. Al-Qaeda lost the sanctuaries from which it planned its attacks; many of its leaders were killed or captured; and its central communications were severely disrupted.

Then the Bush administration succumbed to hubris and made the colossal mistake of invading Iraq without broad international support. Iraq provided the symbols, civilian casualties, and recruiting ground that the Islamic extremists had sought in Afghanistan. Iraq was US President George W. Bush's gift to Osama bin Laden.

Al-Qaeda lost its central organizational capacity, but it became a symbol and focal point around which like-minded imitators could rally. With the help of the Internet, its symbols and training materials became easily available around the world. Whether al-Qaeda had a direct role in the Madrid and London bombings or the recent plot to blow up airliners over the Atlantic, is less important than the way it has been transformed into a powerful "brand." The second round went to the extremists.

The outcome of future rounds in the struggle against Islamic terrorism will depend on our ability to avoid the trap of "jujitsu politics." That will require more use of the soft power of attraction rather than relying so heavily on hard military power, as the Bush administration has done. The struggle is not a clash of Islam against the West, but a civil war within Islam between a minority of terrorists and a larger mainstream of non-violent believers.

Extremism cannot be defeated unless the mainstream wins. Military force, intelligence and international police cooperation needs to be used against hard-core terrorists affiliated with or inspired by al-Qaeda, but soft power is essential to attracting the mainstream and drying up support for the extremists.

US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld once said that the measure of success in this war is whether the number of terrorists we are killing and deterring is larger than the number that the terrorists are recruiting. By this standard, we are doing badly. In November 2003, the official number of terrorist insurgents in Iraq was given as 5,000. This year, it was reported to be 20,000. As Brigadier General Robert Caslen, the Pentagon's deputy director for the war on terrorism, put it: "We are not killing them faster than they are being created."

We are also failing in the application of soft power, Caslen said: "We in the Pentagon are behind our adversaries in the use of communication -- either to recruit or train."

The manner in which we use military power also affects Rumsfeld's ratio. In the aftermath of Sept. 11, there was a good deal of sympathy and understanding around the world for the US' military response against the Taliban. The US invasion of Iraq, a country that was not connected to the Sept. 11 attacks, squandered that goodwill, and the attractiveness of the US in Muslim countries like Indonesia plummeted from 75 percent approval in 2000 to half that level today.

Occupying a divided nation is always messy, and it is bound to produce episodes like Abu Ghraib and Haditha, which undercut the US' attractiveness not just in Iraq, but around the world.

The ability to combine hard and soft power is smart power. When the Soviet Union invaded Hungary and Czechoslovakia during the Cold War, it undercut the soft power that it had enjoyed in Europe in the aftermath of World War II. When Israel launched a lengthy bombing campaign in Lebanon in July, it created so many civilian casualties that the early criticisms of Hezbollah by Egypt, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia became untenable in Arab politics.

When terrorist excesses killed innocent Muslim civilians such as Egypt's Islamic Jihad did in 1993 or Abu Musab al-Zarqawi did in Amman last year, they undercut their own soft power and lost support.

The most important lesson five years after Sept. 11 is that failure to combine hard and soft power effectively in the struggle against terrorism will lead us into the trap set by those who want a clash of civilizations. Muslims, including Islamists, have a diversity of views, so we need to be wary of strategies that help our enemies by uniting disparate forces behind one banner.

We have a just cause and many potential allies, but our failure to combine hard and soft power into a smart strategy could be fatal.

Joseph Nye is a professor at Harvard University.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

On April 19, former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) gave a public speech, his first in about 17 years. During the address at the Ketagalan Institute in Taipei, Chen’s words were vague and his tone was sour. He said that democracy should not be used as an echo chamber for a single politician, that people must be tolerant of other views, that the president should not act as a dictator and that the judiciary should not get involved in politics. He then went on to say that others with different opinions should not be criticized as “XX fellow travelers,” in reference to

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its

Taiwan People’s Party Legislator-at-large Liu Shu-pin (劉書彬) asked Premier Cho Jung-tai (卓榮泰) a question on Tuesday last week about President William Lai’s (賴清德) decision in March to officially define the People’s Republic of China (PRC), as governed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), as a foreign hostile force. Liu objected to Lai’s decision on two grounds. First, procedurally, suggesting that Lai did not have the right to unilaterally make that decision, and that Cho should have consulted with the Executive Yuan before he endorsed it. Second, Liu objected over national security concerns, saying that the CCP and Chinese President Xi