The message of the Butler Report and the US Senate Select Committee on Intelligence has been the same. The British and US intelligence services have been compromised and politicized.

Their findings on Iraq were edited to deliver the conclusions the prime minister and president wanted, justifying an invasion the two had already decided on.

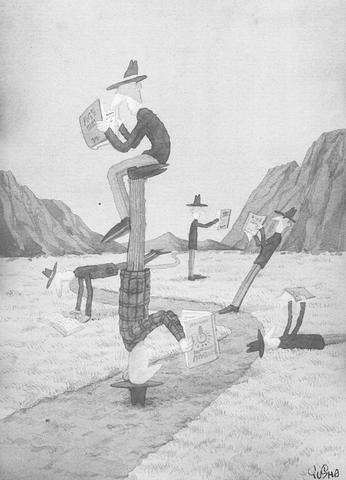

Criticism has in the past focused on the issue of deliberate bias or lies introduced into the evidence by interested ideological or exile groups. But more pernicious in the end was probably the analytical distortion produced by the conventional wisdom.

YUSHA

Lies risk being challenged and discredited. The conventional wisdom carries no risk for the person who invokes it. It has become what "everybody knows."

The conventional wisdom of Western intelligence before Iraq's invasion was that former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein possessed chemical and biological weapons, and an active program for acquiring nuclear weapons.

Chemical weapons were not a great success during the Iran-Iraq war, although they were used by Saddam against passive civilian populations inside Iraq.

His government tried to develop nuclear weapons before the Gulf war, presumably for deterrent purposes, and for prestige and blackmail (since no non-suicidal scenario was ever offered for their offensive use by Iraq; and, while the Baath leadership did stupid things, it never gave sign of a self-destructive tendency: quite the contrary).

This history automatically led intelligence agencies after the Gulf war in 1991 to think that, despite UN strictures and inspections, Saddam would go on pursuing a deterrent weapon. That he would give it all up seemed unlikely. But "seemed" is not an intelligence finding.

The consensus that prevailed in Western intelligence agencies contributed to their reciprocal "intoxication" of one another, as French President Jacques Chirac remarked. Chirac has been in office long enough to take a disabused if not cynical view of anything he is told.

The institutional damage of this affair for the UK's Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) and the CIA is great. The relationship between the two is an old one. The SIS launched modern US intelligence. It has remained ever since in a troubling superiority/dependency relationship with its rich transatlantic equivalents.

Beginning with the carefully managed visit to the UK in July 1940 of the New York lawyer William "Wild Bill" Donovan, as then president Franklin Roosevelt's special envoy, British intelligence fostered and educated the US intelligence and political warfare organization that Donovan, on Roosevelt's orders, established in 1941.

SIS showed its new cousins some of its secrets and trained American recruits to the US Office of Strategic Services. It reached an agreement on dividing the world for secret intelligence operations, excluding the US from most secret intelligence work in Europe and establishing strict rules of protocol.

The cold war, US money and muscle -- and the Cambridge spies plus George Blake -- changed this, making the SIS increasingly a subcontractor to the CIA. It nonetheless remained the only friendly global intelligence network, and brains sometimes trumped money and brute force.

At some point, probably recently, probably as a consequence of the shift in US policy after Sept. 11 and the decision of British Prime Minister Tony Blair to back to the hilt US President George W Bush's ill-defined and open-ended "war on terror," the intelligence relationship took a disastrous tip.

Each side began to reinforce the other's mistakes, and to feed one another's needs to supply intelligence findings that reinforced the preconceptions and rationalized the actions of a prime minister and a president who had already decided to go to war.

The findings that were supplied have since blown up in their faces, to their considerable political disadvantage.

There had been, in fact if not intention, a collaborative intelligence corruption. Had the London-Washington intelligence intimacy been less, the scramble to please would not have enjoyed transatlantic reinforcement; the dissenters in the two agencies would have been less easily dismissed, and the final output closer to the truth. Many now dead might be alive, and much misery avoided.

The Senate Committee report findings have made it possible for Bush to say he went wrong only because he believed what the CIA told him. Now former CIA director George Tenet is gone, CIA reforms will make it impossible for this to happen again. The November voter can be reassured.

It is not so simple for Blair. He, his government, and the SIS have suffered most from the affair. Until now, British intelligence has had a high reputation in Washington, Western Europe and elsewhere. The Butler report's citation of material sent to the prime minister's office in Downing Street (and parliament), stripped of the qualifications that said it came from sources "open to doubt," "severely flawed," later "withdrawn as unreliable," or only included for its "eye-catching character," has greatly damaged the SIS' reputation for professionalism and political integrity.

This is important for a political reason, connected to the UK's relationship to the EU. Europe's respect for the SIS as an intelligence service is one of the UK's most important international assets, ranking with the British armed services in the respect it commands in Europe.

The debate anticipating the promised British referendum on the European Constitution (and euro membership) will press the UK toward a final decision on its degree of commitment to the EU.

The British government and political class continue to assume that their rival US and European relationships can be managed without drama, but this may not remain true.

The policies of the Bush administration and Blair's resolute commitment to Bush's leadership have undermined that assumption for many Europeans. They expect the US election day in November to be a crucial date in the Euro-American relationship.

They assume that if Bush is given a new mandate, international affairs will continue to be dominated by a US government with unilateralist, preemptive and politically utopian policies. They conclude that events will deepen existing tension and divisions between the US and Europe, and that the argument that puts forward the shared values of Americans and Europeans would no longer be convincing.

Here the British intelligence relationship with the CIA becomes a serious problem. Western Europeans have in the past made grudging allowance for the SIS compromising Washington intimacies, and for the UK's deep involvement in a US-British-Canadian-Australian communications interception system that is widely thought by Europeans to be exploited for commercial advantage.

A second problem is Blair's decision to restructure British armed forces to function as subordinate units led by the US. This renunciation of the primordial capacity for autonomous national defense seems to them an abdication of sovereignty, far more important than anything implied in the European constitution. It will leave France as the only European country other than Russia that is capable of autonomous and integrated air, sea and ground operations under national command.

Some Europeans would welcome Bush's re-election, believing it would make inevitable a decision by the bulk of the EU countries to construct a serious European political and strategic entity. They think that essential, and want the UK to belong to it. But they argue that if the UK votes to reject a European constitution, both sides should take that decision as final.

The conflict in the Middle East has been disrupting financial markets, raising concerns about rising inflationary pressures and global economic growth. One market that some investors are particularly worried about has not been heavily covered in the news: the private credit market. Even before the joint US-Israeli attacks on Iran on Feb. 28, global capital markets had faced growing structural pressure — the deteriorating funding conditions in the private credit market. The private credit market is where companies borrow funds directly from nonbank financial institutions such as asset management companies, insurance companies and private lending platforms. Its popularity has risen since

The Donald Trump administration’s approach to China broadly, and to cross-Strait relations in particular, remains a conundrum. The 2025 US National Security Strategy prioritized the defense of Taiwan in a way that surprised some observers of the Trump administration: “Deterring a conflict over Taiwan, ideally by preserving military overmatch, is a priority.” Two months later, Taiwan went entirely unmentioned in the US National Defense Strategy, as did military overmatch vis-a-vis China, giving renewed cause for concern. How to interpret these varying statements remains an open question. In both documents, the Indo-Pacific is listed as a second priority behind homeland defense and

Every analyst watching Iran’s succession crisis is asking who would replace supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Yet, the real question is whether China has learned enough from the Persian Gulf to survive a war over Taiwan. Beijing purchases roughly 90 percent of Iran’s exported crude — some 1.61 million barrels per day last year — and holds a US$400 billion, 25-year cooperation agreement binding it to Tehran’s stability. However, this is not simply the story of a patron protecting an investment. China has spent years engineering a sanctions-evasion architecture that was never really about Iran — it was about Taiwan. The

In an op-ed published in Foreign Affairs on Tuesday, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairwoman Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) said that Taiwan should not have to choose between aligning with Beijing or Washington, and advocated for cooperation with Beijing under the so-called “1992 consensus” as a form of “strategic ambiguity.” However, Cheng has either misunderstood the geopolitical reality and chosen appeasement, or is trying to fool an international audience with her doublespeak; nonetheless, it risks sending the wrong message to Taiwan’s democratic allies and partners. Cheng stressed that “Taiwan does not have to choose,” as while Beijing and Washington compete, Taiwan is strongest when