Undoing a weapons program is one of the rarest of decisions for an absolute leader.

After South Africa's apartheid government was replaced by black majority rule, South Africa astonished the world by disclosing that it had developed six nuclear weapons and then allowing the UN nuclear inspections agency, the International Atomic Energy Agency, to disarm it. That decision, in effect, was the result of a naturally occurring "regime change."

Libya's important and welcome decision to abandon its unconventional weapons programs is all the more interesting since the same government that got Libya into the business of developing forbidden weapons has now ordered the change of course.

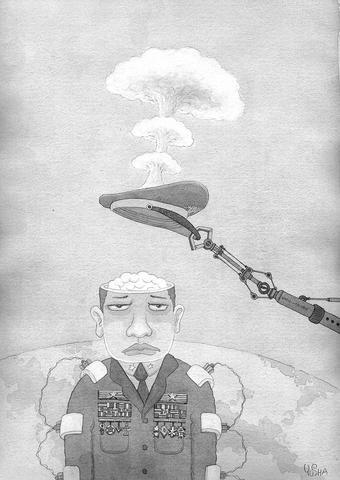

ILLUSTRATION MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

But the larger issue is whether North Korea and Iran can be similarly disarmed and, if so, how best to go about it.

Libya never got very far down the nuclear road and its weapons programs were not enough of a worry to rate inclusion in the "axis of evil" proclaimed by US President George W. Bush in his State of the Union speech in 2002 (Iraq, Iran and North Korea made the cut).

While Libya had acquired centrifuges on the black market, it had not yet assembled them into a large-scale cascade for producing highly enriched uranium. When it came to a nuclear arsenal, Libya was abandoning a distant -- but still dangerous -- dream, not a real ability.

North Korea and Iran are much tougher cases and ultimately a far more important test of the Bush administration's efforts to roll back weapon programs through a mixture of force and diplomacy, rather than the more traditional reliance on weak international treaties and policing.

US intelligence agents project that North Korea has already got one or two nuclear weapons and the ability to expand this presumed nuclear arsenal. Iran has also been working energetically toward developing a nuclear weapons capacity, US intelligence says. It remains to be seen if the signing this month of an agreement on international inspections will eventually halt those efforts.

The turnabout by the Libyan leader, Colonel Muammar Qaddafi -- and the secret British and US diplomacy that encouraged it -- amount to just one step on the road to stopping proliferation, and the question is how to take the next ones.

From the start, the Bush team has said that their policy toward Iraq was about more than just Iraq. The Bush administration began the year with an audacious doctrine that held that removing former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein from power would send a cautionary message to weapons proliferators and help remake the Middle East.

As it heads into an election year, the Bush administration has highlighted the role that US power may have played in changing the Libyan leader's mind. Top Libyan officials, by contrast, have pointed to economic considerations.

The possibility of ending decades of punishing economic sanctions might indeed have led Qaddafi, who has ruled for 34 years and wants to stay in power, to chart a new course even if the Iraq war had not occurred.

Still, it may be that the US invasion of Iraq reinforced the message that the pursuit of forbidden weapons did not strengthen his government. The administration of former US president Ronald Reagan, after all, ordered Air Force F-111s and Navy A-6s to bomb Libya in 1986 after concluding that Libya was behind an attack on US servicemen in Europe.

There is no indication of a similar change of heart in North Korea, where there are indications that North Korean leader Kim Jong-il has drawn a very different lesson from the Iraq war. Having seen how the leader of Iraq was transformed into a prisoner, North Korea appears to have concluded that the best protection against a US intervention is a nuclear arsenal, the bigger the better.

Instead of renouncing its nuclear program, North Korea has in the past year advertised its supposed advances in making nuclear weapons. The Bush administration has turned particularly to China -- as well as to Russia, South Korea and Japan -- to try to advance diplomacy, but has in effect found itself with little leverage.

Threatening military force is not an option. War on the heavily armed Korean Peninsula would be a calamity. No Asian ally is prepared to back a policy of confrontation. With most of the US Army preoccupied with Iraq and Afghanistan, the US simply lacks the military muscle to marshal a credible threat.

In talks, North Korea has proved to be frustrating and possibly untrustworthy. The Bush administration, meanwhile, has oscillated between a hard-line policy of waiting for North Korea's collapse and trying to engage the North in bargaining.

If there is hope of replicating the Libyan reversal it may be in Iran.

First, Iran has not yet developed nuclear weapons. So it would be giving up a prospective, and not actual, ability. Second, a diplomatic process is already under way.

Gary Samore, a senior fellow at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London and a former proliferation expert on the National Security Council under former US President Bill Clinton, notes that Iran has responded to diplomatic pressure -- from Europe and the US -- and temporarily suspended its previously clandestine efforts to enrich uranium at its Natanz site.

What is needed now is a permanent solution, one in which Iran will permanently forgo efforts to produce nuclear weapons materials by enriching uranium or producing plutonium.

European nations have offered Iran access to fuel supplies for a peaceful nuclear program if it gives up its ambitions to develop nuclear weapons.

Whether the US would be party to such a deal and whether Iran would embrace it, Samore notes, are unclear.

"In the case of North Korea the Libya model is unrealistic," he said in a telephone interview. "It is not plausible that the North Korean regime, given their perception of the world, will give up their missiles and chemical, biological and nuclear programs in exchange for better relations. They view them as essential for their survivability. The best you can do is to achieve limits."

If there is a chance to repeat the Libyan experience, he notes, "the test will come in Iran."

The Donald Trump administration’s approach to China broadly, and to cross-Strait relations in particular, remains a conundrum. The 2025 US National Security Strategy prioritized the defense of Taiwan in a way that surprised some observers of the Trump administration: “Deterring a conflict over Taiwan, ideally by preserving military overmatch, is a priority.” Two months later, Taiwan went entirely unmentioned in the US National Defense Strategy, as did military overmatch vis-a-vis China, giving renewed cause for concern. How to interpret these varying statements remains an open question. In both documents, the Indo-Pacific is listed as a second priority behind homeland defense and

Every analyst watching Iran’s succession crisis is asking who would replace supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Yet, the real question is whether China has learned enough from the Persian Gulf to survive a war over Taiwan. Beijing purchases roughly 90 percent of Iran’s exported crude — some 1.61 million barrels per day last year — and holds a US$400 billion, 25-year cooperation agreement binding it to Tehran’s stability. However, this is not simply the story of a patron protecting an investment. China has spent years engineering a sanctions-evasion architecture that was never really about Iran — it was about Taiwan. The

For Taiwan, the ongoing US and Israeli strikes on Iranian targets are a warning signal: When a major power stretches the boundaries of self-defense, smaller states feel the tremors first. Taiwan’s security rests on two pillars: US deterrence and the credibility of international law. The first deters coercion from China. The second legitimizes Taiwan’s place in the international community. One is material. The other is moral. Both are indispensable. Under the UN Charter, force is lawful only in response to an armed attack or with UN Security Council authorization. Even pre-emptive self-defense — long debated — requires a demonstrably imminent

Since being re-elected, US President Donald Trump has consistently taken concrete action to counter China and to safeguard the interests of the US and other democratic nations. The attacks on Iran, the earlier capture of deposed of Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro and efforts to remove Chinese influence from the Panama Canal all demonstrate that, as tensions with Beijing intensify, Washington has adopted a hardline stance aimed at weakening its power. Iran and Venezuela are important allies and major oil suppliers of China, and the US has effectively decapitated both. The US has continuously strengthened its military presence in the Philippines. Japanese Prime