Imagine for a moment that you are a senior official in Iran's foreign ministry. It's hot outside on the dusty, congested streets of Tehran. But inside the ministry, despite the air-conditioning, it's getting stickier all the time. You have a big problem, a problem that Iranian President Mohammad Khatami admits is "huge and serious."

The problem is the George W. Bush administration and, specifically, its insistence that Iran is running "an alarming clandestine nuclear weapons program." You fear that this, coupled with daily US claims that Iran is aiding al-Qaeda, is leading in only one direction. US news reports reaching your desk indicate that the Pentagon is now advocating "regime change" in Iran.

Reading dispatches from Geneva, you note that the US abruptly walked out of low-level talks there last week, the only bilateral forum for two countries lacking formal diplomatic relations. You worry that bridge-building by Iran's UN ambassador is getting nowhere. You understand that while Britain and the EU are telling Washington that engagement, not confrontation, is the way forward, the reality, as Iraq showed, is that if President George W. Bush decides to do it his way, there is little the Europeans or indeed Russia can ultimately do to stop him.

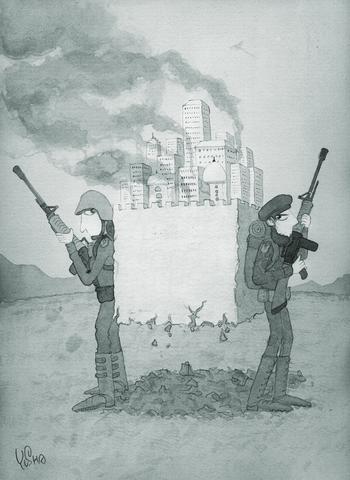

What is certain is that at almost all points of the compass, the unmatchable US military machine besieges Iran's borders. The Pentagon is sponsoring the Iraq-based Mujahedin e-Khalq, a group long dedicated to insurrection in the Islamic republic that the Department of State describes as terrorists. And you are fully aware that Israel is warning Washington that unless something changes soon, Iran may acquire the bomb within two years. As the temperature in the office rises, as flies buzz around the desk like F-16s in a dogfight, and as beads of sweat form on furrowed brow, it seems only one conclusion is possible. The question with which you endlessly pestered your foreign missions before and during the invasion of Iraq -- "who's next?" -- appears now to have but one answer. It's us.

So what would you do?

This imaginary official may be wrong, of course. Without some new terrorist enormity in the US "homeland," surely Bush is not so reckless as to start another all-out war as America's election year approaches? Washington's war of words could amount to nothing more than that. Maybe the US foolishly believes it is somehow helping reformist factions in the Majlis (parliament), the media and student bodies. Maybe destabilization and intimidation is the name of the game and the al-Qaeda claims are a pretext, as in Iraq. Perhaps the US does not itself know what it wants to do. But who knows? Tehran's dilemma is real -- Washington's intentions are dangerously uncertain.

Should Iran continue to deny any present bomb-making intent and facilitate additional, short-notice inspections by the International Atomic Energy Agency to prove it? Should it expand its EU dialogue and strengthen protective ties with countries such as Syria, Lebanon, India, Russia and China, which is its present policy? The answer is "yes." The difficulty is that this may not be enough.

Should it then go further and cancel its nuclear-power contracts with Moscow? Should it abandon Hezbollah and Palestinian rejectionist groups, as the US demands? This doubtless sounds like a good idea to neo-con thinktankers. But surely even they can grasp that such humiliation, under duress from the Great Satan, is politically unacceptable. Grovelling is not Persian policy.

Even the relatively moderate Khatami made it clear in Beirut recently that there would be no backtracking in the absence of a just, wider Middle East settlement. And anyway, Khatami does not control Iran's foreign and defense policy. Indeed, it is unclear who does. Ayatollah Ali Khomeini, ex-president Hashemi Rafsanjani, security chief Hassan Rohani, and the military and intelligence agencies all doubtless have a say, which may be why Iran's policies often appear contradictory. Tension between civil society reformers and the mullahs is endemic and combustible. But as US pressure has increased, so too has the sway of Islamic hardliners.

Iran's alternative course is the worst of all, but one which Bush's threats make an ever more likely choice. It is to build and deploy nuclear weapons and missiles in order to pre-empt America's regime-toppling designs. The US should hardly be surprised if it comes to this. After all, it is what Washington used to call deterrence before it abandoned that concept in favor of "anticipatory defense" or, more candidly, unilateral offensive warfare.

To Iran, the US now looks very much like the Soviet Union looked to Western Europe at the height of the Cold War. Britain and West Germany did not waive their right to deploy US cruise and Pershing nuclear missiles to deter the combined menace of overwhelming conventional forces and an opposing, hostile ideology.

Why, in all logic, should Iran, or for that matter North Korea and other so-called "rogue states" accused of developing weapons of mass destruction, act any differently?

If this is Iran's choice, the US will be much to blame. While identifying the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction as the main global threat, its bellicose post-Sept. 11 policies have served to increase rather than reduce it. Washington ignores, as ever, its exemplary obligation to disarm under the nuclear non-proliferation treaty (NPT). Despite strategic reductions negotiated with Russia, the US retains enormous firepower in every nuclear-weapons category.

Worse still, the White House is set on developing, not just researching, a new generation of battlefield "mini-nukes" whose only application is offensive use, not deterrence. Its new US$400 billion defense budget allocates funding to this work; linked to this is an expected US move to end its nuclear test moratorium in defiance of the comprehensive test-ban treaty.

Bush has repeatedly warned, not least in his national security strategy, that the US is prepared to use "overwhelming force," including first use of nuclear weapons, to crush perceived or emerging threats. It might well have done so in Iraq had the war gone badly. Bush has thereby torn up the key stabilizing concept of "negative security assurance" by which nuclear powers including previous US administrations pledged, through the NPT and the UN, not to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear states.

Meanwhile the US encourages egregious double standards. What it says, in effect, is that Iran (and most other states) must not be allowed a nuclear capability but, for example, Israel's undeclared and internationally uninspected arsenal is permissible. India's and Pakistan's bombs, although recently and covertly acquired, are tolerated too, since they are deemed US allies. Bush's greatest single disservice to non-proliferation came in Iraq.

The US cried wolf in exaggerating former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein's capability. Now it is actively undermining the vital principle of independent, international inspection and verification by limiting UN access to the country. Yet would Iraq have been attacked if it really had possessed nuclear weapons? Possibly not. Thus the self-defeating, mangled message to Iran and others is: arm yourselves to the teeth, before it's too late, or you too could face the chop.

Small wonder if things grow sticky inside Tehran's dark-windowed ministries. If Iran ultimately does the responsible thing and forswears the bomb, it will not be for want of the most irresponsible American provocation.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) challenges and ignores the international rules-based order by violating Taiwanese airspace using a high-flying drone: This incident is a multi-layered challenge, including a lawfare challenge against the First Island Chain, the US, and the world. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) defines lawfare as “controlling the enemy through the law or using the law to constrain the enemy.” Chen Yu-cheng (陳育正), an associate professor at the Graduate Institute of China Military Affairs Studies, at Taiwan’s Fu Hsing Kang College (National Defense University), argues the PLA uses lawfare to create a precedent and a new de facto legal

Chile has elected a new government that has the opportunity to take a fresh look at some key aspects of foreign economic policy, mainly a greater focus on Asia, including Taiwan. Still, in the great scheme of things, Chile is a small nation in Latin America, compared with giants such as Brazil and Mexico, or other major markets such as Colombia and Argentina. So why should Taiwan pay much attention to the new administration? Because the victory of Chilean president-elect Jose Antonio Kast, a right-of-center politician, can be seen as confirming that the continent is undergoing one of its periodic political shifts,

In the first year of his second term, US President Donald Trump continued to shake the foundations of the liberal international order to realize his “America first” policy. However, amid an atmosphere of uncertainty and unpredictability, the Trump administration brought some clarity to its policy toward Taiwan. As expected, bilateral trade emerged as a major priority for the new Trump administration. To secure a favorable trade deal with Taiwan, it adopted a two-pronged strategy: First, Trump accused Taiwan of “stealing” chip business from the US, indicating that if Taipei did not address Washington’s concerns in this strategic sector, it could revisit its Taiwan

Taiwan’s long-term care system has fallen into a structural paradox. Staffing shortages have led to a situation in which almost 20 percent of the about 110,000 beds in the care system are vacant, but new patient admissions remain closed. Although the government’s “Long-term Care 3.0” program has increased subsidies and sought to integrate medical and elderly care systems, strict staff-to-patient ratios, a narrow labor pipeline and rising inflation-driven costs have left many small to medium-sized care centers struggling. With nearly 20,000 beds forced to remain empty as a consequence, the issue is not isolated management failures, but a far more