When TV Guide updates its 1999 list of greatest commercials of all time, I must root against the current occupant of the No. 1 position: Apple Computer's 1984, broadcast for the 1984 Super Bowl. The ad's indelible image -- a sledgehammer thrown at Big Brother -- makes good art for a museum installation. But for transcendent greatness in the real world, the top spot should go to a more recent instance of Apple-sponsored genius: the iPod commercials. (It doesn't matter which one.)

Their shimmying and shaking have firmly established the iPod as the icon of the dawning digital lifestyle and sped 10 million units out the door. Without saying a word, the commercials present viewers with a choice: orgiastic boogaloo-ing with the in crowd, or standing forlornly out of the picture. And now the price of admission is just US$99.

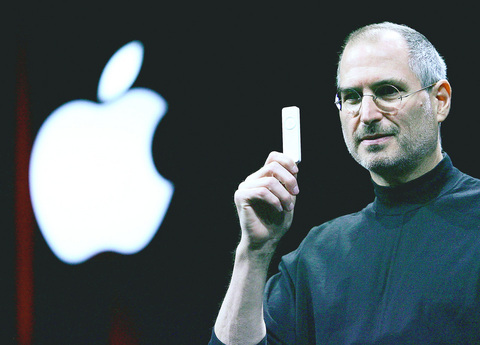

PHOTO: AFP

In the weeks leading up to the Macworld Exposition in San Francisco last week, some of the Mac faithful expressed concern that the iPod's phenomenal success was diverting the attention of Apple's chief executive, Steve Jobs, away from the Mac. Apple announced record quarterly earnings last week; the results showed that the iPod and iTunes accounted for almost 40 percent of the company's revenue last quarter, up from 15 percent in the quarter a year earlier. Whatever the percentages, children need to be reassured that Dad loves all equally. But the iPod has shown Jobs new ways to think about Apple's future, which arguably has never looked better.

`The only asset that matters'

Consider some competitors. Microsoft has a near-monopoly on the basic software used on the hardware owned by most people, enabling the company to extract what is basically a head tax. Google has a near-monopoly in the digital library business, which enables it to do very well with advertising that monetizes eyeballs. But Apple has an absolute monopoly on the asset that is the most difficult for competitors to copy: cool.

Paul Saffo, research director of the Institute for the Future in Menlo Park, California, says emphatically, "Hipness is the only asset that matters." Jobs had not been able to leverage it in traditional computers because technology in crucial areas had not matured enough to make cool affordably practical on a mass scale. To the extent that cool is based on exclusion of the uncool, Apple was too hip for its own long-term health.

With the introduction of the iPod in 2002, however, Jobs offered a product that combined cool with inexpensive, truly personal computing that fits in a pocket. Thanks to technological progress, Jobs now has at his disposal ridiculously cheap processing and memory, which render meaningless the distinction between computer and peripheral. To paraphrase Sun Microsystems, the peripheral is the computer.

Saffo points out that the iPod and its competitors use identical hardware components. What permits one to so outdistance the others, he says, is "how they are put together" -- in Apple's case, with yet-to-be-matched software and essential cool. Playing at the top of his game, Jobs can lead the way to ubiquitous, headache-free, plug-and-play computing, including every definition of "play" and taking a variety of forms.

The science of cool

Computer and component companies have long been trying to break out of the industrial park, starting even before computing became personal. In 1972, Intel -- yes, Intel -- started a digital lifestyle initiative of sorts when it acquired Microma, a start-up that made digital watches. Intel's chief executive, Gordon Moore, predicted that prices would fall, but even he could not always anticipate the speed of the phenomenon.

Intel executives were also unacquainted with the science of cool and the dictates of fashion. Five years later, Intel's board decided to bail, taking a loss of about US$1.3 million in the sale. In the telling of the story in Tim Jackson's book Inside Intel (Dutton, 1997), Moore wore a Microma watch for years afterward, waiting for anyone to ask him about it so he could explain that it was the most expensive watch he had ever owned.

In 1979, not long after Intel left the consumer electronics business, Apple let Jef Raskin, employee No. 31, head a small team to design an inexpensive personal computer with a graphical screen -- an easy-to-use appliance for ordinary people who were not passionate hobbyists. He called it the Macintosh. When Jobs joined the project, he and Raskin tangled about many details: Jobs wanted a more powerful processor and a mouse, for example; Raskin, trying to keep the retail price below US$1,000, didn't. Raskin left unhappily in 1981. Jobs won that battle, but he was still two decades away from fulfilling the vision of the inexpensive, friendly computing appliance he had inherited.

The design team tried to keep down costs so that the Mac would hit stores at US$1,500, but little necessities nudged the total upward. They were soon looking at US$1,995. That was before John Sculley, then the chief executive, and other suits weighed in just before the introduction. To the team's disgust, the final price was US$2,495.

Even at that price, the machine was woefully underpowered and ill-equipped, as cool as conceptual art but no more useful. In Steven Levy's history of the Mac, Insanely Great (Viking, 1994), a core member of the design team, Joanna Hoffman, looked back with wonder: "It's a miracle that it sold anything at all." Orders started strongly, then plunged, and in 1985 it was Jobs' turn to go out the door unhappily, exiled for 12 years.

Bringing down the price

I have not owned a Mac since 1995. I confess, however, that the just-announced US$499 Mac Mini has grabbed my attention -- just as Jobs anticipated -- by offering an inexpensive way for homes with Windows machines to add a Mac or two. With time working in his favor two decades after the Mac's introduction, he can offer a bare-bones machine with a 2,000-fold increase in memory, compared with the original.

Will Jobs take the next step, aggressively reclaiming market share from Windows by releasing a version of the Macintosh operating system for Intel-equipped machines, as his critics (including me) have long called for? Probably not. The opportunity to widely license the operating system has passed. The typical user needs minimal software, caring little or not at all what operating system is behind the screen. With the growing competition from Linux, the free open-source operating system, the Windows head tax on Intel machines will disappear anyway. Microsoft has already had to swallow new pricing models to retain a presence in third-world countries. Last fall, Advanced Micro Devices, the chip manufacturer, introduced a supply-your-own-monitor computer with Windows CE for a suggested retail price of US$185.

Apple is well positioned for the future. When consumers open their wallets to buy things that have machine intelligence, or provide digital entertainment, or link to the Internet - that is, just about everything in a household that is not edible -- they are likely to be drawn to the company with cachet, offering the best-designed, best-engineered, easiest-to-use products, priced affordably thanks to Moore's old law and Jobs' new pragmatism. They'll turn to the company that best knows how to meld hardware and software, the company embodied in the ecstatically happy hipster silhouette. The company that is, in a word, cool.

Apple has US$6.4 billion in cash, a seemingly small sum next to Microsoft's $64 billion. But it is Microsoft, the poor little rich kid, who must be envious of Apple. All of the billions in its corporate treasury, all of the personal billions of the co-founders Bill Gates and Paul Allen, all of the money in the world, cannot buy the ability to fathom the metaphysical mystery of cool.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) yesterday said it is closely monitoring developments in Venezuela, and would continue to cooperate with democratic allies and work together for regional and global security, stability, and prosperity. The remarks came after the US on Saturday launched a series of airstrikes in Venezuela and kidnapped Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, who was later flown to New York along with his wife. The pair face US charges related to drug trafficking and alleged cooperation with gangs designated as terrorist organizations. Maduro has denied the allegations. The ministry said that it is closely monitoring the political and economic situation

UNRELENTING: China attempted cyberattacks on Taiwan’s critical infrastructure 2.63 million times per day last year, up from 1.23 million in 2023, the NSB said China’s cyberarmy has long engaged in cyberattacks against Taiwan’s critical infrastructure, employing diverse and evolving tactics, the National Security Bureau (NSB) said yesterday, adding that cyberattacks on critical energy infrastructure last year increased 10-fold compared with the previous year. The NSB yesterday released a report titled Analysis on China’s Cyber Threats to Taiwan’s Critical Infrastructure in 2025, outlining the number of cyberattacks, major tactics and hacker groups. Taiwan’s national intelligence community identified a large number of cybersecurity incidents last year, the bureau said in a statement. China’s cyberarmy last year launched an average of 2.63 million intrusion attempts per day targeting Taiwan’s critical

‘SLICING METHOD’: In the event of a blockade, the China Coast Guard would intercept Taiwanese ships while its navy would seek to deter foreign intervention China’s military drills around Taiwan this week signaled potential strategies to cut the nation off from energy supplies and foreign military assistance, a US think tank report said. The Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) conducted what it called “Justice Mission 2025” exercises from Monday to Tuesday in five maritime zones and airspace around Taiwan, calling them a warning to “Taiwanese independence” forces. In a report released on Wednesday, the Institute for the Study of War said the exercises effectively simulated blocking shipping routes to major port cities, including Kaohsiung, Keelung and Hualien. Taiwan would be highly vulnerable under such a blockade, because it

UNDER WAY: The contract for advanced sensor systems would be fulfilled in Florida, and is expected to be completed by June 2031, the Pentagon said Lockheed Martin has been given a contract involving foreign military sales to Taiwan to meet what Washington calls “an urgent operational need” of Taiwan’s air force, the Pentagon said on Wednesday. The contract has a ceiling value of US$328.5 million, with US$157.3 million in foreign military sales funds obligated at the time of award, the Pentagon said in a statement. “This contract provides for the procurement and delivery of 55 Infrared Search and Track Legion Enhanced Sensor Pods, processors, pod containers and processor containers required to meet the urgent operational need of the Taiwan air force,” it said. The contract’s work would be