When Russians started being arrested for opposing the Ukraine offensive, Maria felt the same kind of fear she guessed her ancestors, victims of repression under Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, must have lived through.

Now two and a half years into its military offensive, Russia has imprisoned hundreds for protesting or speaking out against the campaign — even in private — in a crackdown that has paralyzed the Kremlin’s domestic critics.

“It’s not normal when you start behaving like your ancestors did. Twitching every time the phone rings... thinking all the time about who you are talking with and what you are talking about,” said Maria, a 47-year-old from Moscow.

Photo: AFP

Leafing through a book with photos of victims of Stalin’s purges, Maria pointed to her great-grandfather.

Of Polish origin, he was declared an “enemy of the people” and executed in 1938 for “spying.” He was posthumously rehabilitated after Stalin’s death in 1953.

His wife was also targeted, spending four years in the gulag, the Soviet network of harsh prison labor camps. Maria’s grandmother, who had to live with the stigma of her parents being dubbed “enemies of the people,” constantly worried she too would be arrested.

Maria now feels a similar fear, concerned she could be labeled a “foreign agent” — a modern-day label with Stalin-era connotations that is used to marginalize critics of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s regime.

Putin’s Russia also has harsher legal tools at its disposal to target its opponents.

Under military censorship laws, people can be convicted for up to 15 years for spreading “false information” about the military campaign in Ukraine.

In such a climate, Maria, an English professor at a university, is cautious about how she behaves and what she says in public.

Outside her circle of close friends, she hides her pacifist convictions and her fondness for Ukrainian culture.

She does not discuss politics with her colleagues, and lives in fear that somebody could denounce her for reading Western news or social media sites blocked in Russia that she accesses through a VPN.

English itself is now considered an “enemy language” that raises suspicions, said Maria, who asked for her surname to be withheld.

When she is reading news articles on her phone on public transport, she said she “immediately closes” the page and starts playing a game “if I realize there is a person next to me not reading anything but just looking around.”

Fearing her phone would be searched at passport control, she cleanses it before traveling of any chats where the fighting in Ukraine might have been mentioned.

She is also afraid to wear her vyshyvanka, a traditional stitched Ukrainian shirt, in public, and shuns combining yellow and blue clothes — the colors of the Ukrainian flag.

After a brief eruption of anti-conflict rallies in February 2022, the Kremlin has since stymied almost all shows of public opposition.

“People do not dare to protest, do not dare to speak out,” said Svetlana Gannushkina, a prominent Russian rights activist who has been labelled a “foreign agent.”

Heavy sentences for regime critics along with harsh treatment of prisoners has scared many into silence, she said.

Gannushkina pointed to what she called a “historical, maybe even genetic, fear” in a country that has seen multiple bouts of political repression — from serfdom in the Russian Empire, the Bolsheviks’ “Red Terror” after the 1917 Revolution and the 1930s purges under Stalin.

Her Memorial group worked to preserve the memory of victims of communist repression and campaigned against modern rights violations until Russian authorities shut it down in 2021.

Throughout history, repression has repeatedly “divided society into those who were ready to submit and those who did not want to, understood that resistance leads to nothing, and left,” Gannushkina said. “History has made a kind of natural selection... And now we’ve got a whole generation of people who are not ready to resist.”

For Soviet dissident Alexander Podrabinek, 71, fear “is not an ethnic, national or genetic peculiarity” specific to Russia.

“I have visited several totalitarian countries besides the Soviet Union and the situation is basically the same everywhere,” he said. “Fear is the main obstacle to a normal life in our country... Fear demoralizes people, deprives them of their freedom.”

“Someone who is afraid is no longer free. They become a slave to their fear, living without being able to realize their potential,” he added.

Podrabinek was exiled to Russia’s Siberia in 1978 and then imprisoned in 1981 after writing a book on punitive psychiatry in the Soviet Union. Despite pressure from the KGB security services, he refused to leave the country.

“The only thing that can overcome fear is the conviction that you are right,” he said.

Packed crowds in India celebrating their cricket team’s victory ended in a deadly stampede on Wednesday, with 11 mainly young fans crushed to death, the local state’s chief minister said. Joyous cricket fans had come out to celebrate and welcome home their heroes, Royal Challengers Bengaluru, after they beat Punjab Kings in a roller-coaster Indian Premier League (IPL) cricket final on Tuesday night. However, the euphoria of the vast crowds in the southern tech city of Bengaluru ended in disaster, with Indian Prime Minister Narendra calling it “absolutely heartrending.” Karnataka Chief Minister Siddaramaiah said most of the deceased are young, with 11 dead

By 2027, Denmark would relocate its foreign convicts to a prison in Kosovo under a 200-million-euro (US$228.6 million) agreement that has raised concerns among non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and residents, but which could serve as a model for the rest of the EU. The agreement, reached in 2022 and ratified by Kosovar lawmakers last year, provides for the reception of up to 300 foreign prisoners sentenced in Denmark. They must not have been convicted of terrorism or war crimes, or have a mental condition or terminal disease. Once their sentence is completed in Kosovan, they would be deported to their home country. In

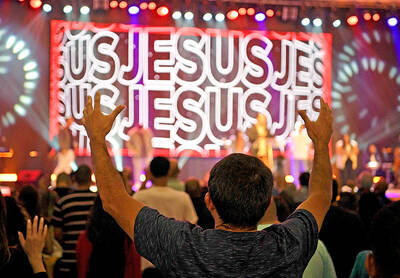

Brazil, the world’s largest Roman Catholic country, saw its Catholic population decline further in 2022, while evangelical Christians and those with no religion continued to rise, census data released on Friday by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) showed. The census indicated that Brazil had 100.2 million Roman Catholics in 2022, accounting for 56.7 percent of the population, down from 65.1 percent or 105.4 million recorded in the 2010 census. Meanwhile, the share of evangelical Christians rose to 26.9 percent last year, up from 21.6 percent in 2010, adding 12 million followers to reach 47.4 million — the highest figure

LOST CONTACT: The mission carried payloads from Japan, the US and Taiwan’s National Central University, including a deep space radiation probe, ispace said Japanese company ispace said its uncrewed moon lander likely crashed onto the moon’s surface during its lunar touchdown attempt yesterday, marking another failure two years after its unsuccessful inaugural mission. Tokyo-based ispace had hoped to join US firms Intuitive Machines and Firefly Aerospace as companies that have accomplished commercial landings amid a global race for the moon, which includes state-run missions from China and India. A successful mission would have made ispace the first company outside the US to achieve a moon landing. Resilience, ispace’s second lunar lander, could not decelerate fast enough as it approached the moon, and the company has