In the shadow of Lahore’s centuries-old Badshahi Mosque, Zohaib Hassan plucks at the strings of a sarangi, filling the streets with a melodious hum and cry.

Remarkable for its resemblance to the human voice, the classical instrument is fading from Pakistan’s music scene, except for a few players dedicated to preserving its place.

Difficult to master, expensive to repair and with little financial reward for professionals, the sarangi’s decline has been difficult to halt, Hassan told reporters.

Photo: AFP

“We are trying to keep the instrument alive, not even taking into account our miserable financial condition,” he said.

For seven generations, his family has mastered the bowed, short-necked instrument and Hassan is well-respected across Pakistan for his abilities, regularly appearing on television, radio and at private parties.

“My family’s craze for the instrument forced me to pursue a career as a sarangi player, leaving my education incomplete,” he said. “I live hand-to-mouth as the majority of directors arrange musical programmes with the latest orchestras and pop bands.”

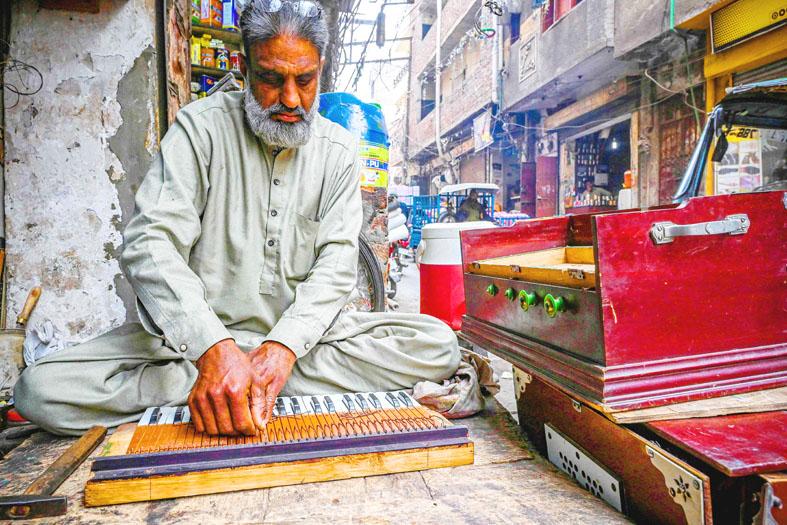

Photo: AFP

Traditional instruments are competing with a booming rhythm and blues and pop scene in a country where more than 60 percent of the population is aged under 30.

Sara Zaman, a teacher of classical music at the National Council of Arts in Lahore, said that alongside the sarangi, other traditional instruments such as the sitar, santoor and tanpura are also dying out.

“Platforms have been given to other disciplines like pop music, but it has been missing in the case of classical music,” Zaman said. “The sarangi, being a very difficult instrument, has not been given due importance and attention in Pakistan leading to its gradual demise.”

The sarangi gained prominence in Indian classical music in the 17th century, during the reign of the Mughals in the subcontinent.

Its decline began in the 1980s after the death of several master players and classical singers in the country, said Khwaja Najam-ul-Hassan, a television director who has created an archive of Pakistan’s leading musicians.

“The instrument was close to the hearts of the top internationally acclaimed male and female classical singers, but it began to fade away after they died,” Najam-ul-Hassan said.

Ustad Allah Rakha, one of Pakistan’s most globally acclaimed sarangi players, died in 2015 after a career that saw him perform with orchestras around the world.

Now players say they struggle to survive on performance fees alone, often much smaller than those paid to modern guitarists, pianists or violinists.

Carved by hand from a single block of cedar native to parts of Pakistan, the sarangi’s primary strings are made of goat gut, while the 17 sympathetic strings — a common feature on subcontinent folk instruments — are steel.

The instrument costs about 120,000 rupees (US$625) and most of its parts are imported from India, where it remains a principal part of the canon.

“The price has gone up as there is a ban on imports from India,” said Muhammad Tahir, the owner of one of only two repair shops in Lahore.

Pakistan downgraded diplomatic ties and stopped bilateral trade with India over New Delhi’s decision in 2019 to strip the disputed Jammu & Kashmir region of its semi-autonomous status.

Tahir, who spends about two months carefully restoring a single worn-out sarangi, said that no one in Pakistan manufactures the special steel strings because of the lack of demand.

“There is no admiration for sarangi players and the few people who are repairing this wonderful instrument,” said Ustad Zia-ud-Din, the owner of the other Lahore repair shop, which has existed in some form for 200 years.

Efforts to adapt to the modern music scene have shown pockets of promise.

“We have invented new ways of playing, including making the sarangi semi-electric to enhance the sound during performances with modern musical instruments,” Hassan said.

He has now performed several times with the adapted instrument and says the reception has been positive.

One of the few students is 14-year-old musician Mohsin Muddasir, who has shunned instruments such as the guitar to take on the sarangi.

“I am learning this instrument because it plays with the strings of my heart,” Muddasir said.

The death of a former head of China’s one-child policy has been met not by tributes, but by castigation of the abandoned policy on social media this week. State media praised Peng Peiyun (彭珮雲), former head of China’s National Family Planning Commission from 1988 to 1998, as “an outstanding leader” in her work related to women and children. The reaction on Chinese social media to Peng’s death in Beijing on Sunday, just shy of her 96th birthday, was less positive. “Those children who were lost, naked, are waiting for you over there” in the afterlife, one person posted on China’s Sina Weibo platform. China’s

‘NO COUNTRY BUMPKIN’: The judge rejected arguments that former prime minister Najib Razak was an unwitting victim, saying Najib took steps to protect his position Imprisoned former Malaysian prime minister Najib Razak was yesterday convicted, following a corruption trial tied to multibillion-dollar looting of the 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) state investment fund. The nation’s high court found Najib, 72, guilty on four counts of abuse of power and 21 charges of money laundering related to more than US$700 million channeled into his personal bank accounts from the 1MDB fund. Najib denied any wrongdoing, and maintained the funds were a political donation from Saudi Arabia and that he had been misled by rogue financiers led by businessman Low Taek Jho. Low, thought to be the scandal’s mastermind, remains

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese yesterday announced plans for a national bravery award to recognize civilians and first responders who confronted “the worst of evil” during an anti-Semitic terror attack that left 15 dead and has cast a heavy shadow over the nation’s holiday season. Albanese said he plans to establish a special honors system for those who placed themselves in harm’s way to help during the attack on a beachside Hanukkah celebration, like Ahmed al-Ahmed, a Syrian-Australian Muslim who disarmed one of the assailants before being wounded himself. Sajid Akram, who was killed by police during the Dec. 14 attack, and

Shamans in Peru on Monday gathered for an annual New Year’s ritual where they made predictions for the year to come, including illness for US President Donald Trump and the downfall of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro. “The United States should prepare itself because Donald Trump will fall seriously ill,” Juan de Dios Garcia proclaimed as he gathered with other shamans on a beach in southern Lima, dressed in traditional Andean ponchos and headdresses, and sprinkling flowers on the sand. The shamans carried large posters of world leaders, over which they crossed swords and burned incense, some of which they stomped on. In this