At 92, Giddes Chalamanda has no idea what TikTok is. He does not even own a smartphone. And yet the Malawian music legend has become a social media star, with his song Linny Hoo garnering more than 80 million views on the video-sharing platform, and spawning mashups and remixes from South Africa to the Philippines.

“They come and show me the videos on their phones, but I have no idea how it works,” Chalamanda told reporters at his home in Madzuwa on the edge of a macadamia plantation, about 20km from Malawi’s main city, Blantyre.

However, “I love the fact that people are enjoying themselves and that my talent is getting the right attention,” he said, speaking in Chewa.

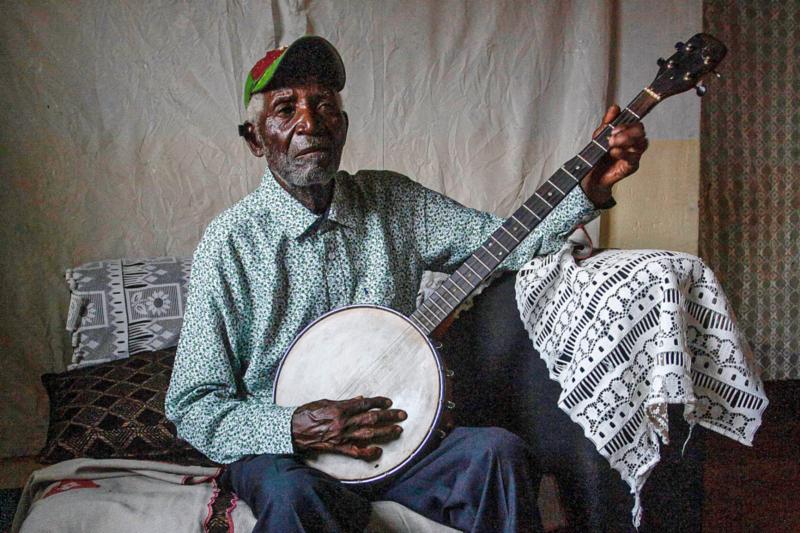

Photo: AFP

Despite his gray hair and slight stoop, the nonagenarian singer and guitarist, who has been a constant presence on the Malawian music scene for seven decades, displays a youthful exuberance as he sits chatting with a group of young fans.

He first recorded Linny, an ode to one of his daughters, in 2000, but global acclaim only came two decades later when Patience Namadingo, a young gospel artist, teamed up with Chalamanda to record a reggae remix of Linny titled Linny Hoo.

The black-and-white video of the recording shows a smiling, gap-toothed Chalamanda, nattily dressed in a white shirt and V-neck sweater, jamming with Namadingo under a tree outside his home, with a group of neighbors looking on.

The video went viral after it was posted on YouTube, where it racked up more than 6.9 million views. Then late last year, it landed on TikTok and toured the globe.

Chalamanda only learned of the song’s sensational social media popularity from his children and their friends.

Since then he and Namadingo have recorded remixes of several others of his best-known tracks.

Linny’s 16-year-old son Stepson Austin told reporters that he was proud of his grandfather’s longevity.

“It is good that he has lived long enough to see this day,” said the youngster, who himself aspires to become a hip-hop artist.

Born in Chiradzulu, a small town in southern Malawi, Chalamanda won fame in his homeland with lilting songs such as Buffalo Soldier, in which he dreams of visiting the US, and Napolo.

Over the past decade, he has collaborated with several younger musicians and still performs across the country.

On TikTok, DJs and ordinary fans have created their own remixes as part of a #LinnyHooChallenge.

“When his music starts playing in a club or at a festival, everyone gets the urge to dance. That is how appealing it is,” musician and long-time collaborator Davis Njobvu told reporters. “The fact that he has been there long enough to work with the young ones is special.”

South Africa-based music producer Joe Machingura attributed the global appeal of a song recorded in Chewa, one of Malawi’s most widely spoken languages, to the sentiments underlying it.

“The old man sang with so much passion, it connects with whoever listens to it,” Machingura said.

“It speaks to your soul,” he said.

Chalamanda, a twice-married father of 14 children, only seven of whom, including Linny, are still alive, said that he has no idea how to secure royalties for the TikTok plays.

Chalamanda and his wife hope to benefit financially from his newfound stardom.

“I am just surprised that despite the popularity of the song, there is nothing for me,” he said.

“While I am excited that I have made people dance all around the world, there should be some gain for me,” he said. “I need the money.”

His manager Pemphero Mphande told reporters that he was looking into the issue and the Copyright Society of Malawi said it was ready to assist.

Arts curator Tammy Mbendera of the Festival Institute in Malawi credited platforms like TikTok with creating new opportunities for African talent.

“With songs from our past especially, they were written with such profoundness that they still can resonate today,” Mbendera said.

“All one has to do really, is get the chance to experience it, to acknowledge its significance. I think that’s what happened here,” she said.

Shamans in Peru on Monday gathered for an annual New Year’s ritual where they made predictions for the year to come, including illness for US President Donald Trump and the downfall of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro. “The United States should prepare itself because Donald Trump will fall seriously ill,” Juan de Dios Garcia proclaimed as he gathered with other shamans on a beach in southern Lima, dressed in traditional Andean ponchos and headdresses, and sprinkling flowers on the sand. The shamans carried large posters of world leaders, over which they crossed swords and burned incense, some of which they stomped on. In this

Indonesia yesterday began enforcing its newly ratified penal code, replacing a Dutch-era criminal law that had governed the country for more than 80 years and marking a major shift in its legal landscape. Since proclaiming independence in 1945, the Southeast Asian country had continued to operate under a colonial framework widely criticized as outdated and misaligned with Indonesia’s social values. Efforts to revise the code stalled for decades as lawmakers debated how to balance human rights, religious norms and local traditions in the world’s most populous Muslim-majority nation. The 345-page Indonesian Penal Code, known as the KUHP, was passed in 2022. It

Near the entrance to the Panama Canal, a monument to China’s contributions to the interoceanic waterway was torn down on Saturday night by order of local authorities. The move comes as US President Donald Trump has made threats in the past few months to retake control of the canal, claiming Beijing has too much influence in its operations. In a surprising move that has been criticized by leaders in Panama and China, the mayor’s office of the locality of Arraijan ordered the demolition of the monument built in 2004 to symbolize friendship between the countries. The mayor’s office said in

‘TRUMP’S LONG GAME’: Minnesota Governor Tim Walz said that while fraud was a serious issue, the US president was politicizing it to defund programs for Minnesotans US President Donald Trump’s administration on Tuesday said it was auditing immigration cases involving US citizens of Somalian origin to detect fraud that could lead to denaturalization, or revocation of citizenship, while also announcing a freeze of childcare funds to Minnesota and demanding an audit of some daycare centers. “Under US law, if an individual procures citizenship on a fraudulent basis, that is grounds for denaturalization,” US Department of Homeland Security Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin said in a statement. Denaturalization cases are rare and can take years. About 11 cases were pursued per year between 1990 and 2017, the Immigrant Legal Resource