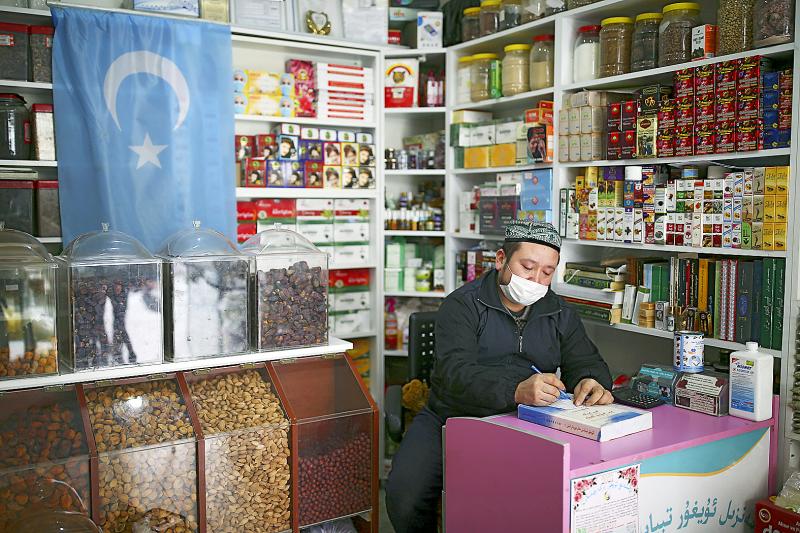

Abdullah Metseydi, a Uighur in Turkey, was readying for bed last month when he heard commotion, then pounding on the door followed by: “Police. Open the door.”

A dozen or more officers poured in, many bearing guns and wearing the camouflage of Turkey’s anti-terror force. They asked if Metseydi had participated in any movements against China and threatened to deport him and his wife.

They took him to a deportation facility, where he sits at the center of a brewing political controversy.

Photo: AP

Opposition legislators in Turkey are accusing Ankara’s leaders of secretly selling out Uighurs to China in exchange for COVID-19 vaccines. Tens of millions of vials of promised Chinese vaccines have not yet been delivered.

Meanwhile, in the past few months, Turkish police have raided and detained about 50 Uighurs in deportation centers, lawyers say — a sharp uptick from last year.

Although no hard evidence has yet emerged for a quid pro quo, the legislators and Uighurs fear that Beijing is using the vaccines as leverage to win passage of an extradition treaty.

The treaty was signed years ago, but suddenly ratified by China in December, and could come before Turkish lawmakers as soon as this month.

Uighurs said the bill could bring their ultimate life-threatening nightmare: Deportation back to a country they fled to avoid mass detention.

More than a million Uighurs and other largely Muslim minorities have been swept into prisons and detention camps in China, in what China calls an anti-terrorism measure, but the US has declared a genocide.

“I’m terrified of being deported,” said Melike, Metseydi’s wife, through tears, declining to give her last name for fear of retribution. “I’m worried for my husband’s mental health.”

Suspicions of a deal emerged when the first shipment of Chinese vaccines was held up for weeks in December. Officials blamed permit issues.

Even now, Turkish Legislator Yildirim Kaya, of the country’s main opposition party, said that China has delivered only a third of the 30 million doses it promised by the end of last month.

Turkey is largely reliant on China’s Sinovac vaccine to immunize its population against the virus.

“Such a delay is not normal. We have paid for these vaccines,” Kaya said. “Is China blackmailing Turkey?”

Kaya said he has formally asked the Turkish government about pressure from China, but has not yet received a response.

Turkish and Chinese authorities have said that the extradition bill is not meant to target Uighurs for deportation. Chinese state media called such concerns “smearing.”

Turkish Minister of Foreign Affairs Mevlut Cavusoglu said in December last year that the vaccine delay was not related to Uighurs.

“We do not use the Uighurs for political purposes, we defend their human rights,” Cavusoglu said.

Abdurehim Parac, a Uighur poet detained twice in the past few years, said even detention in Turkey was “hotel-like” compared to the “hellish” conditions he was subjected to during three years in Chinese prison.

Imim was eventually released after a judge cleared his name, but he has difficulty sleeping at night out of fear that the extradition bill might be ratified, and called the pressure “unbearable.”

“Death awaits me in China,” he said.

Rising fears are already prompting an influx of Uighurs moving to Germany, the Netherlands and other European countries. Some are so desperate they are even sneaking across borders illegally, said Ali Kutad, who fled China for Turkey in 2016.

“Turkey is our second homeland,” Kutad said. “We’re really afraid.”

By 2027, Denmark would relocate its foreign convicts to a prison in Kosovo under a 200-million-euro (US$228.6 million) agreement that has raised concerns among non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and residents, but which could serve as a model for the rest of the EU. The agreement, reached in 2022 and ratified by Kosovar lawmakers last year, provides for the reception of up to 300 foreign prisoners sentenced in Denmark. They must not have been convicted of terrorism or war crimes, or have a mental condition or terminal disease. Once their sentence is completed in Kosovan, they would be deported to their home country. In

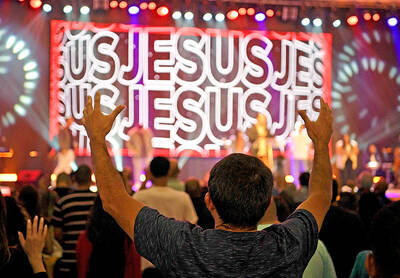

Brazil, the world’s largest Roman Catholic country, saw its Catholic population decline further in 2022, while evangelical Christians and those with no religion continued to rise, census data released on Friday by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) showed. The census indicated that Brazil had 100.2 million Roman Catholics in 2022, accounting for 56.7 percent of the population, down from 65.1 percent or 105.4 million recorded in the 2010 census. Meanwhile, the share of evangelical Christians rose to 26.9 percent last year, up from 21.6 percent in 2010, adding 12 million followers to reach 47.4 million — the highest figure

A Chinese scientist was arrested while arriving in the US at Detroit airport, the second case in days involving the alleged smuggling of biological material, authorities said on Monday. The scientist is accused of shipping biological material months ago to staff at a laboratory at the University of Michigan. The FBI, in a court filing, described it as material related to certain worms and requires a government permit. “The guidelines for importing biological materials into the US for research purposes are stringent, but clear, and actions like this undermine the legitimate work of other visiting scholars,” said John Nowak, who leads field

LOST CONTACT: The mission carried payloads from Japan, the US and Taiwan’s National Central University, including a deep space radiation probe, ispace said Japanese company ispace said its uncrewed moon lander likely crashed onto the moon’s surface during its lunar touchdown attempt yesterday, marking another failure two years after its unsuccessful inaugural mission. Tokyo-based ispace had hoped to join US firms Intuitive Machines and Firefly Aerospace as companies that have accomplished commercial landings amid a global race for the moon, which includes state-run missions from China and India. A successful mission would have made ispace the first company outside the US to achieve a moon landing. Resilience, ispace’s second lunar lander, could not decelerate fast enough as it approached the moon, and the company has