For more than a half-century, a mysterious caste system has shadowed the life of every North Korean. It can decide whether they will live in the gated compounds of the minuscule elite, or in mountain villages where farmers hack at rocky soil with handmade tools. It can help determine what hospital will take them if they fall sick, whether they go to college and, very often, whom they will marry.

It is called songbun. And officially it does not exist at all.

However, the power of caste, which North Korean exiles and scholars say was permanently branded onto every family based on their supposed ideological purity, is also quietly fraying, weakened by the growing importance of something that barely existed until recently in socialist North Korea: wealth.

Like almost all change in North Korea’s deeply opaque society, where so much is hidden to outsiders, the shift is happening slowly and often silently.

However, in the contest for power within the closed world that Pyongyang has created, defectors, analysts and activists say money is now competing with the domination of political caste.

“There’s one place where songbun doesn’t matter, and that’s in business,” said a North Korean soldier-turned-businessman who fled to South Korea after a prison stint and who now lives in a working-class apartment building on the fringes of Seoul. “Songbun means nothing to people who want to make money.”

Songbun, a word that translates as “ingredient,” but effectively means “background,” first took shape in the 1950s and 1960s.

It was a time when North Korea’s founder Kim Il-sung was forging one of the world’s most repressive states and seeking ways to reward supporters and isolate potential enemies.

Songbun, which historians say was partially modeled on societal divisions in the Soviet Union, turned North Korea’s fiercely hierarchical society upside down, pushing peasants to the top of the caste ladder and aristocrats and landlords toward the bottom. The very top was reserved for those closest to Kim: His relatives and guerrillas who had fought with him against Korea’s Japanese occupiers.

Very quickly, though, songbun became a professional hierarchy. The low caste became farmers and miners. The high caste filled the powerful bureaucracies. And children grew up and stepped into their parents’ roles.

“If you were a peasant and you owned nothing, then all of a sudden you were at the top of the society,” said Bob Collins, who wove together smuggled documents, interviews with former North Korean security officials and discussions with an array of ordinary North Koreans to write an exhaustive songbun study released this year by the Washington-based Committee for Human Rights in North Korea.

While the songbun system theoretically allows for movement within the hierarchy, Collins said most families’ standing today remains a reflection of their ancestors’ position in the 1950s and 1960s. Generations after the system began, many of North Korea’s most powerful people are officially identified as “peasants.”

However, starting in the mid-1990s and accelerating in recent years, songbun — long the arbiter of North Korean life — became one part of something far more complicated.

“Songbun cannot collapse. Because that would mean the collapse of the entire system,” said Kim Hee-tae, head of the Seoul-based group Human Rights, which maintains a network of contacts in the North. “But people increasingly believe that money is more important than your background.”

Despite its power, songbun is an almost-silent presence. Few people ever see their own songbun paperwork. Few low-caste families speak of it at all, exiles say, left mute by incomprehension and fear.

It is only when young people stumble into glass ceilings, normally when applying to universities or for jobs, that they begin to understand the years of slights.

Eventually, most grow to understand and accept its power, but they rarely have more than a general idea of where they fit into the pecking order, experts said.

In a country where secrecy is reflexive, the state simply denies it exists.

“This is all nonsense,” a North Korean government minder said, interrupting a visiting journalist when he tried to ask a woman about her family’s songbun. “People make up lies about my country.”

Certainly, few ordinary North Koreans understand the staggering and sometimes shifting complexities of songbun, which at its core divided the entire population into three main categories — “core,” “wavering” and “hostile” classes — and subdivided those into some four dozen subcategories.

North Koreans with songbun good enough for the top jobs will still likely get minimal salaries, but perks for the elite could include a good apartment in Pyongyang, regular electricity, access to quality medical clinics and easier admission to top schools for their children. In a culture where parents have immense influence over the choice of their children’s spouses, high-songbun partners are prized.

However, to be caught at the bottom is to be lost in a nightmare of bloodline and bureaucracy, defectors say.

“My family was in the lowest of the lowest level,” said a former North Korean coal miner who fled to South Korea in 2006, hoping to give his young sons opportunities outside the mines. “Someone from the state was always watching what we were saying, watching what we were doing ... The state treated us as if they were doing us a favor simply by allowing us to live.” The man, like other North Korean refugees interviewed for this story, spoke on condition he not be named, fearing that relatives still in the North would be punished.

When he was a boy he had hoped to be a doctor or perhaps a government official. He was a top student, he says.

However, when colleges kept rejecting him, his father finally told him the truth: His father, it turned out, had been born in South Korea, served in its army and been taken prisoner during the Korean War.

Like thousands of other southern prisoners-of-war, he disappeared into the North’s prison gulag and then was forced into the coal mines. With songbun like that, his choices were few. He would never become a government official. Getting into college, and perhaps eventually landing nonpolitical work, would have required impossibly large bribes.

North Korea’s growing network of small informal markets, a path out of desperate poverty for some, had yet to arrive in his village, deep in the countryside.

“I couldn’t live my dreams because of my father,” said the thin, ropy man, with the biceps of someone who spent 17 years swinging a pick deep underground.

However, while North Korea is often portrayed as a Soviet throwback stranded in the 1950s, a reputation it earned with decades of isolation and single-family rule, strains of change do ripple beneath its Stalinist exterior. That has created a complex and uneasy relationship between songbun and wealth.

Most North Koreans have never met a foreigner, seen the Internet or earned more than a couple hundred dollars a month — but those in a growing economic elite now fly to Beijing and Singapore to shop.

It is a country where human rights groups say well over 100,000 political prisoners are held in a series of isolated prison camps, but where an exclusive European firm, Kempinski, hopes to be running a hotel soon.

The market economy first took hold during the rule of former North Korean leader Kim Jong-il, the son of the nation’s founder, who ran the country from the 1990s until his death late last year, when his son then took control.

In the mid-1990s, poor harvests and the end of Soviet assistance lead to widespread famine. Official controls relaxed as hunger tore at the country.

Reluctantly, the government allowed the establishment of informal markets, with ordinary people setting up stalls to sell food, clothes or cheap consumer goods.

Since then, the government has alternately allowed the markets to flourish and cracked down on them, leaving many people working in legally gray areas.

Two former Chilean ministers are among four candidates competing this weekend for the presidential nomination of the left ahead of November elections dominated by rising levels of violent crime. More than 15 million voters are eligible to choose today between former minister of labor Jeannette Jara, former minister of the interior Carolina Toha and two members of parliament, Gonzalo Winter and Jaime Mulet, to represent the left against a resurgent right. The primary is open to members of the parties within Chilean President Gabriel Boric’s ruling left-wing coalition and other voters who are not affiliated with specific parties. A recent poll by the

TENSIONS HIGH: For more than half a year, students have organized protests around the country, while the Serbian presaident said they are part of a foreign plot About 140,000 protesters rallied in Belgrade, the largest turnout over the past few months, as student-led demonstrations mount pressure on the populist government to call early elections. The rally was one of the largest in more than half a year student-led actions, which began in November last year after the roof of a train station collapsed in the northern city of Novi Sad, killing 16 people — a tragedy widely blamed on entrenched corruption. On Saturday, a sea of protesters filled Belgrade’s largest square and poured into several surrounding streets. The independent protest monitor Archive of Public Gatherings estimated the

Irish-language rap group Kneecap on Saturday gave an impassioned performance for tens of thousands of fans at the Glastonbury Festival despite criticism by British politicians and a terror charge for one of the trio. Liam Og O hAnnaidh, who performs under the stage name Mo Chara, has been charged under the UK’s Terrorism Act with supporting a proscribed organization for allegedly waving a Hezbollah flag at a concert in London in November last year. The rapper, who was charged under the anglicized version of his name, Liam O’Hanna, is on unconditional bail before a further court hearing in August. “Glastonbury,

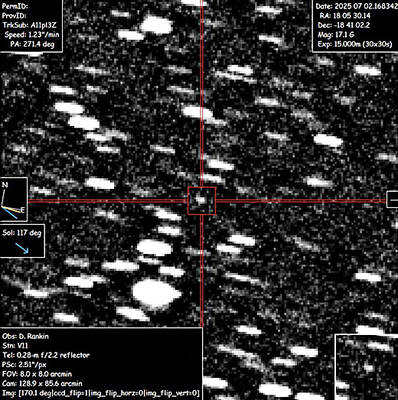

FLYBY: The object, appears to be traveling more than 60 kilometers per second, meaning it is not bound by the sun’s orbit, astronomers studying 3I/Atlas said Astronomers on Wednesday confirmed the discovery of an interstellar object racing through the solar system — only the third-ever spotted, although scientists suspect many more might slip past unnoticed. The visitor from the stars, designated 3I/Atlas, is likely the largest yet detected, and has been classified as a comet, or cosmic snowball. “It looks kind of fuzzy,” said Peter Veres, an astronomer with the International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Center, which was responsible for the official confirmation. “It seems that there is some gas around it, and I think one or two telescopes reported a very short tail.” Originally known as A11pl3Z before