US professor Robert Lieberman went to Myanmar to train local filmmakers and shot his own documentary on the sly. The solo-filmed They Call it Myanmar: Lifting the Curtain pries the lid off daily life in what has long been one of world’s most isolated and repressed places, examining its grinding poverty and tragic decades of military rule.

The film is a reminder that, despite recent upbeat news as Myanmar ventures on a reform path that has seen releases of political prisoners and easing of censorship, it remains a country with huge problems.

The movie is showing at selected theaters in the US.

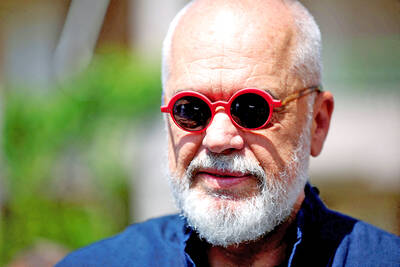

Lieberman, 71, took time off from his regular job teaching physics at Cornell University and traveled to Myanmar several times over two years, initially on a US government-funded Fulbright program. He helped shoot health awareness commercials, then taught film at a university in the main city, Yangon. He also accumulated 120 hours of his own footage, often filmed clandestinely.

Part documentary, part travelogue, They Call it Myanmar absorbs the country’s charms and cruelties and spills them out with disarming curiosity. He explains, both from his own perspective and the narrations by anonymous collaborators, just what life is like there and what makes its long-suffering people tick.

In a sense, the film is already outdated. Lieberman did the leg work before change began taking hold, although he sneaked back early last year to interview democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi after she was released from her latest stretch of house arrest.

The Nobel laureate’s musings on the country also known as Burma, and its turbulent history, are part of the narrative.

Lieberman describes Myanmar as the second-most isolated country in the world after North Korea, but foreign journalists are now being allowed in to report, and there is public debate on issues such as human rights and ethnic conflict that just a year ago would have been off-limits.

While the isolation and climate of fear has eased, however, that has not translated yet into a shift in political power or improved living conditions. Lieberman’s film lays bare how far what was once one of Southeast Asia’s most prosperous countries has sunk.

His starting point is not the ruinous military rule that has led it to that point, but, refreshingly, something more simple and vital to Burmese identity: tanaka, a fragrant, light brown paste that people daub on their faces. Opening the movie that way makes sense, as many faces populate Lieberman’s film. They are filmed on the street, on trains, in temples, in markets and clinics, though some are blurred out to protect their identities.

He sometimes injects his own dashes of humor, like when he jokes on seeing a Buddha image covered thick with countless offerings of gold leaf: “Shall we grab it and run?”

The abiding theme, however, is deprivation. In one hard-to-watch scene, a young, shaven-headed girl with a deep ulcer cries in pain at an ill-equipped clinic. The doctor says the girl has tuberculosis, but her mother cannot afford the drugs to treat her.

A political prisoner, interviewed off-camera, tells how he was tortured by his jailers, who put a bag on his head with two mice inside. He says to stop the mice biting him, he had to bite them back.

In the second half of the film, Lieberman looks at Myanmar’s turbulent modern history. There is rare archive footage of Aung San Suu Kyi’s father, national hero General Aung San, speaking during a visit to Britain before he led the country toward independence after World War II, only to be assassinated months before it shook off its colony status.

The film then tells the compelling story of how Aung San Suu Kyi was catapulted to political prominence following a brutal military crackdown on democracy protesters in 1988. The military used deadly force again to put down Buddhist monk-led mass demonstrations in 2007. The junta’s reputation was sullied further by its initial refusal to allow in foreign aid after Cyclone Nargis in 2008, which killed 130,000 people.

However, what is missing from They Call It Myanmar is what beckons now. Even hardened human rights activists and dissidents view the changes of the past year as the country’s most significant in the half-century since the military took power.

The film’s touching closing sequences tell of people’s aspirations. One Burmese tearfully speaks of how Myanmar is a proud country, but one that needs help to stand on its own feet. Another simply yearns “to speak, read and write poetry the way your heart tells you to do it.”

FRAUD ALLEGED: The leader of an opposition alliance made allegations of electoral irregularities and called for a protest in Tirana as European leaders are to meet Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama’s Socialist Party scored a large victory in parliamentary elections, securing him his fourth term, official results showed late on Tuesday. The Socialist Party won 52.1 percent of the vote on Sunday compared with 34.2 percent for an alliance of opposition parties led by his main rival Sali Berisha, according to results released by the Albanian Central Election Commission. Diaspora votes have yet to be counted, but according to initial results, Rama was also leading there. According to projections, the Socialist Party could have more lawmakers than in 2021 elections. At the time, it won 74 seats in the

EUROPEAN FUTURE? Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama says only he could secure EU membership, but challenges remain in dealing with corruption and a brain drain Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama seeks to win an unprecedented fourth term, pledging to finally take the country into the EU and turn it into a hot tourist destination with some help from the Trump family. The artist-turned-politician has been pitching Albania as a trendy coastal destination, which has helped to drive up tourism arrivals to a record 11 million last year. US President Donald Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, also joined in the rush, pledging to invest US$1.4 billion to turn a largely deserted island into a luxurious getaway. Rama is expected to win another term after yesterday’s vote. The vote would

CANCER: Jose Mujica earned the moniker ‘world’s poorest president’ for giving away much of his salary and living a simple life on his farm, with his wife and dog Tributes poured in on Tuesday from across Latin America following the death of former Uruguayan president Jose “Pepe” Mujica, an ex-guerrilla fighter revered by the left for his humility and progressive politics. He was 89. Mujica, who spent a dozen years behind bars for revolutionary activity, lost his battle against cancer after announcing in January that the disease had spread and he would stop treatment. “With deep sorrow, we announce the passing of our comrade Pepe Mujica. President, activist, guide and leader. We will miss you greatly, old friend,” Uruguayan President Yamandu Orsi wrote on X. “Pepe, eternal,” a cyclist shouted out minutes later,

A Croatian town has come up with a novel solution to solve the issue of working parents when there are no public childcare spaces available: pay grandparents to do it. Samobor, near the capital, Zagreb, has become the first in the country to run a “Grandmother-Grandfather Service,” which pays 360 euros (US$400) a month per child. The scheme allows grandparents to top up their pension, but the authorities also hope it will boost family ties and tackle social isolation as the population ages. “The benefits are multiple,” Samobor Mayor Petra Skrobot told reporters. “Pensions are rather low and for parents it is sometimes