The man who beat Floyd Mayweather Jr lives across the street from a burned-out coffee hut with a giant banana painted on its back wall. Around the bend, leaning in the tall grass, is a corroded shed holding ancient farming equipment. Every so often, a horse trots down the craggy road, pulling a splintered cart and a rider toward the center of one of Bulgaria’s poorest towns.

Late on Tuesday morning, the man who beat Mayweather, Serafim Todorov, stood on the curb here. He was in front of the seven-floor concrete apartment building where he, his wife, his son and his pregnant daughter-in-law live in a modest first-floor unit. Todorov talked with his son, Simeon. He watched a horse clop by. He smoked a cigarette. Then he went inside, sat in a chair and, like a teakettle perched on a glowing stove, steamed to a rolling boil as he remembered what happened in Atlanta in the US state of Georgia 19 years ago.

The victory by Todorov, then 27, over Mayweather, then 19, in the semi-finals of the 1996 Olympic boxing tournament was the last time Mayweather lost in the ring. A few months later, Mayweather turned professional and began a career that has produced 47 consecutive victories and hundreds of millions of dollars in earnings. On May 2 in Las Vegas, Mayweather is to have a long-awaited showdown with Manny Pacquiao in what many are calling the richest fight in boxing history.

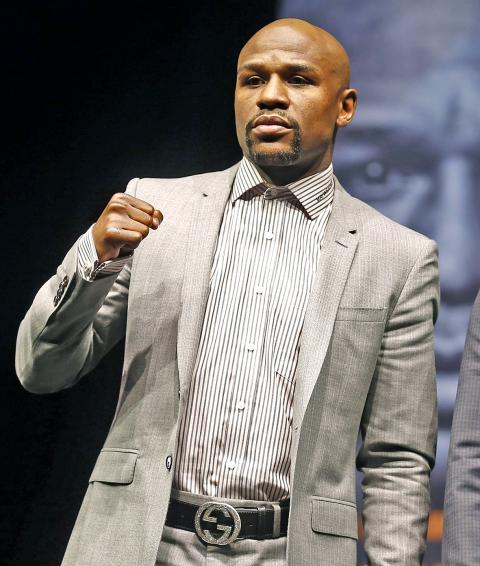

Photo: Reuters

Yet for Todorov, now 45, the stark gap between his life and Mayweather’s since their match — the loser is worth an estimated US$280 million and the winner does not even own a flat-screen TV — is not what roils him. It is the circumstances behind his life’s unraveling that have made him sour.

And in a curious twist, Todorov believes he and Mayweather might have actually been wronged by the same man.

For years, boxing fans — particularly Americans — speculated that Todorov’s victory over Mayweather was, at least in part, a product of suspect judging. Todorov does not discard this theory.

“It’s possible, absolutely,” he said.

However, Todorov’s real fury stems from what happened in the Atlanta final — the match after his win over Mayweather — when he believes he was the one unfairly beaten. He detailed the unspooling that followed: A fallout with his federation, a failed attempt at switching nationalities, missed opportunities abroad and unhealthy offers to work in the Bulgarian underworld.

Today, while Mayweather is preparing to make as much as US$180 million for one fight, Todorov is trying to live on a pension of about 400 euros (US$435) a month. Slumped in a chair, Todorov gestured toward the window that looked out at the coffee hut with the banana on it.

All of this struggle can be traced to what happened in Atlanta, he said.

The fight between Mayweather and Todorov took place on a Friday, two days before the closing ceremonies of the Atlanta Games, at the basketball arena on Georgia Tech’s campus. It began with a flurry of punches, as if the opening bell had twisted a cap off both fighters’ fizzing emotions. As Todorov watched a YouTube video of the bout, his lips curled into a tiny smile.

“He was 19, remember,” Todorov said through an interpreter. “My experience was much stronger. I beat all the Russians, all the Cubans, some Americans, Germans, Olympic champions. I was making fun of them in the ring. British, French — I beat them all.”

‘ARTIST’

“I was very smart,” he said. “I was a very beautiful and attractive fighter to watch. You must be an artist in the ring. I was an artist.”

Hyperbole aside, Todorov’s basic assessment is accurate: Mayweather was a teenager, a Golden Gloves champion, sure, but one who had to overcome a hiccup in Olympic qualifying just to make the US team. He had shown little on the international stage.

Todorov was a three-time world champion, a two-time European champion, a regular in the celebrated German boxing league and the kind of boxer who would occasionally toy with his opponents by feinting and dodging their attacks before reaching around to tap them on the back of the shoulder.

“No, no,” he would taunt them. “I’m over here.”

Todorov, who grew up in Peshtera, a southern town, learned boxing at a young age — his uncle taught him to fight when he was eight — and he quickly developed into a prodigy, a whirling master of the ring whose fundamentals were flawless. Footwork was always his specialty, and even this week, despite having not trained for years, he fell easily into a fighter’s sharp, staccato prowls and bounces when asked for a short demonstration.

Todorov’s weakness was his focus. He liked women and he liked rakia, the fruit brandy popular in many of the Balkan countries. His coach, Georgi Stoimenov, who discovered Todorov as a teenager and worked with him throughout his career, tried his best to control Todorov, but found it difficult.

Todorov does not deny his flaws. He said that before the Atlanta Games, he trained for only about three weeks and even during that period found time to take breaks to go drinking with his friends. He still dominated at the Olympics, shredding his first three opponents by a combined score of 45-18. He said he had done little scouting on Mayweather other than watching his quarter-final match.

“It was just like any other fight, to be honest — I had beaten much stronger fighters,” Todorov said.

However, Mayweather surprised Todorov in the first two rounds. Todorov feinted and used a lot of one-punch attacks while Mayweather pattered in combinations. The fighters went to the final round with Todorov trailing by a point, 7-6.

Still, Todorov was confident.

“I was not afraid to go after him,” he said.

The last three minutes were a mess of flailing blows. Todorov edged Mayweather. In the ring, neither fighter immediately knew who had won because the scoring system was designed to keep the result secret until it was announced.

Both Todorov and Mayweather said afterward that they believed they should have been awarded more points. When the decision was announced, the referee initially raised Mayweather’s arm before correcting his mistake.

Mayweather’s backers thought that Emil Jetchev, a Bulgarian who was the longtime chairman of the international referees’ and judges’ commission, had influenced the judges to favor his countryman, Todorov. That was not a new accusation; South Korean and American boxers similarly suspected Jetchev at the 1988 Olympics in Seoul.

And Todorov agreed with the theory, but for his own reason: He blames Jetchev for his loss in the gold-medal match, contending that he was unfairly beaten, 10-9, by Somluck Kamsing of Thailand.

CONTRACT

After the Mayweather fight, men involved in promoting professional boxing spoke to the two fighters. An interpreter sat next to Todorov. He said that the men had been impressed by Todorov and wanted to sign him to a professional contract.

“They saw my style, they saw me in the ring, they saw that I was white,” Todorov said, grinning at the memory. “There will never be another white boxer like me and they knew this. They wanted me to stay [in the US].”

The terms of the contract were familiar to Todorov, because he had been approached by Australian promoters after he won the 1991 world championship in Sydney, he said.

In Atlanta, he smiled while the interpreter checked off the perks: a big signing bonus, house, car, a new life and big fights in front of big crowds. The other two men leaned in, one of them holding a pen, but Todorov pushed it away, he said.

“Without considering, I said no,” he said. “I just said it quick, like that: ‘No.’”

“You know what happened next?” he said. “The two men went over to Floyd and started talking in English.”

Todorov is not foolish enough to think the men went to Mayweather only because he had rejected their offer, but the image remains burned in his memory all the same. It could have been him, he thinks now. It should have been.

After his defeat in the final, Todorov spent two days in a perpetual stupor as he waited for his flight home.

“I didn’t stop drinking the entire time,” he said. “I just wanted to drink myself to death.”

He felt betrayed. He had brought much attention and adulation to Bulgarian boxing over the years, but now he felt only bitterness. With the 1997 world championships approaching, he met with officials from the Turkish federation and accepted an offer to change his affiliation and fight for Turkey.

The deal was not as rich as the one from the US promoters, but it was substantial. If Todorov won the gold medal, the officials told him, he would receive a reward of US$1 million. All that was needed to process the nationality switch in time was approval from the Bulgarian federation.

“The deal was done,” Todorov said. “And then I got a call telling me that it was off. Jetchev had asked the Turkish federation for a transfer fee of [US]$300,000 at the last second.”

If he had lost to Mayweather, he would have surely continued fighting in an attempt to reach an Olympic final, he said. He would not have wondered about the chance to stay in the US, or about a subsequent betrayal against Kamsing.

“Instead, it all happened and I wanted to hope that things here could get better,” he said. “It was stupid. I came back and I found hell.”

‘DREAM’: The 5-0 victory was PSG’s first Champions League title, and the biggest final win by any team in the 70-year history of the top-flight European competition Paris Saint-Germain won the Champions League for the first time as Luis Enrique’s brilliant young side outclassed Inter on Saturday in the most one-sided final ever with teenager Desire Doue scoring twice in an astonishing 5-0 victory. Doue supplied the pass for Achraf Hakimi to give PSG an early lead and the 19-year-old went from provider to finisher as his deflected shot doubled the advantage in the 20th minute. Doue scored again just after the hour mark, ending any doubt about the outcome before Khvicha Kvaratskhelia ran away to get the fourth and substitute Senny Mayulu, another teenager, made it five. Inter were

FRUSTRATION: Alcaraz made several unforced errors over four sets against Bosnian Damir Dzumhur, who had never made it past the third round in a major competition Defending champion Carlos Alcaraz reached the fourth round of the French Open after laboring past Damir Dzumhur 6-1, 6-3, 4-6, 6-4 in the Friday night session. The second-seeded Spaniard had never before played Dzumhur, a 33-year-old Bosnian who had never been past the third round at any major tournament. “I suffered quite a lot today,” Alcaraz said. “The first two sets was under control, then he started to play more deeply and more aggressively. It was really difficult for me.” Dzumhur hurt his left knee in a fall in the second round, and had treatment on Friday on his right leg during the

The horn sounded on Wednesday night to signal a third straight trip to the Stanley Cup Final, as the Florida Panthers celebrated merely by hopping over the boards and several heading over to congratulate goaltender Sergei Bobrovsky. It was a subdued celebration seemingly more befitting a regular-season win for the reigning Cup champs. “I remember a few years ago, it felt like such an accomplishment from where we were at one point,” forward Matthew Tkachuk said, adding: “It’s all business and we’ve got a bigger goal in mind.” The Panthers closed out the Carolina Hurricanes in five games, with a 5-3 victory in

STRONG CONNECTION: Although she has considered switching nationalities, Garland said that if it was not for Taiwan’s support throughout her career, she would not be in Paris British-Taiwanese player Joanna Garland on Tuesday became the first Taiwanese to clinch a victory in a main singles draw of the French Open since 2020 after she outlasted the US’ Katie Volynets in Paris. The world No. 175, Taiwan’s highest-ranked female player in singles, said she would rely on her self-belief as she prepares for her second-round match at the French Open after overcoming a serious injury to qualify for a maiden Grand Slam appearance. After navigating her way through the qualifiers last week, Garland secured her first win at the main draw of a Grand Slam by battling past world No.