One of BaLiwakes’ best known songs, Penanwang (Puyuma King), contains Puyuma-language lyrics written in Japanese syllabaries, set to the tune of Stephen Foster’s Old Black Joe. Penned around 1964, the words praise the Qing Dynasty-era indigenous leader Paliday not for his heroic deeds, but his willingness to adopt higher-yield Han farming practices and build new roads connecting to the outside world.

“BaLiwakes lived through several upheavals in regime, language and environment. It truly required the courage and wisdom of the Puyuma King in order to maintain his ties to his traditions while facing the future,” writes Tsai Pei-han (蔡佩含) in Flow and Reproduction: Exploring BaLiwakes’ Multilingual Ballad Creations (流動與再製-談陸森寶BaLiwakes的混語歌謠創).

Born in 1910, BaLiwakes was among Taiwan’s first indigenous children to receive a formal Japanese education. He even adopted the Japanese name Mori Hoichiro, which was converted into his Chinese name Lu Sen-pao (陸森寶), which he’s better known as today.

Photo courtesy of National Dong Hwa University

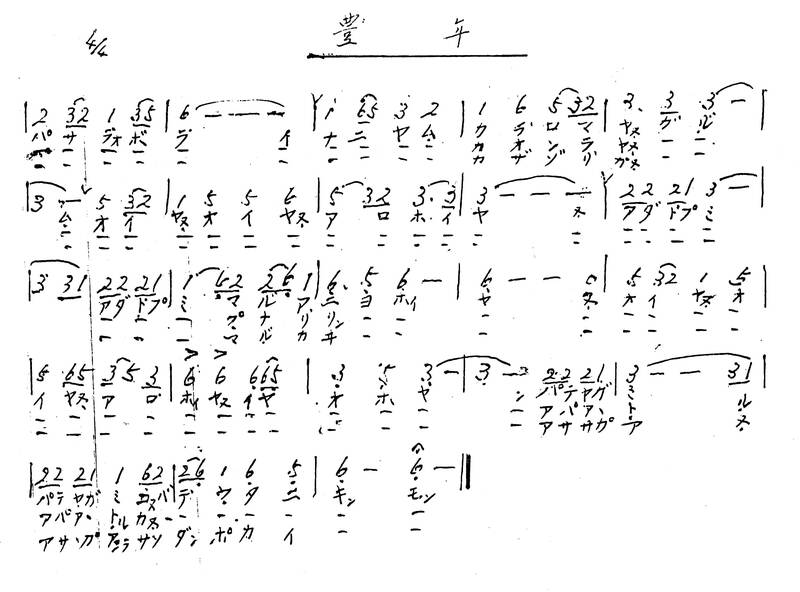

He showed talent in music while attending Tainan Normal School, but didn’t start composing and writing down his lyrics until after World War II. Most traditional Puyuma songs do not have fixed lyrics, containing mostly nonlexical terms such as naluwan and iyahey, BaLiwakes writes in the introduction to a 1984 compilation.

“The reason why I compose and write is because our young people are forgetting their ‘language of the mountains’ (mother tongue) ...” he writes. “When these songs are sung in public or in church, I feel immense joy.”

DESIRE TO LEARN

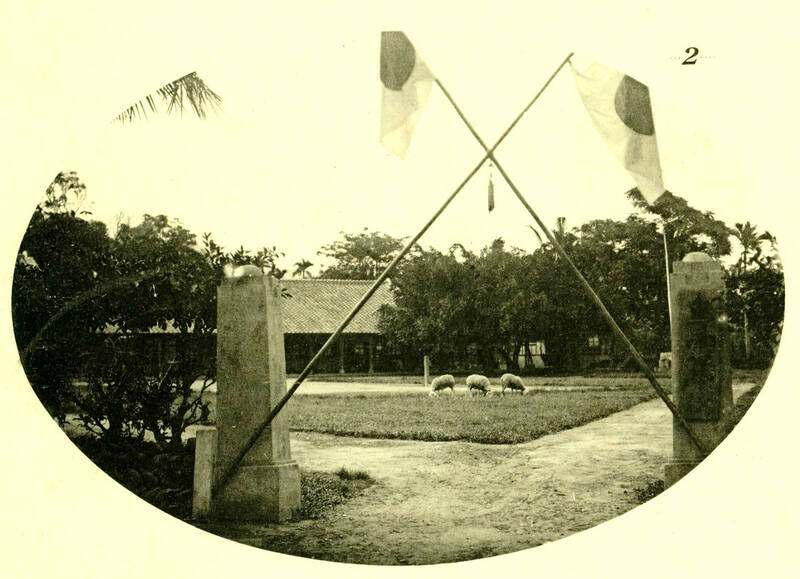

Photo courtesy of Taitung County Cultural Affairs Department

BaLiwakes was born on Nov. 2, 1910 in Puyuma Village, Taitung. He was a frail and sickly child, but he remained ambitious despite his father’s attempts to hold him back due to his health, writes Puyuma educator and politician Paelabang Danapan in Master of teaching by example: the development of BaLiwakes’ character and his times (身教大師 BaLiwakes 的人格教養與時代).

At the age of five, he enrolled in Beinan Public School in place of his elder sister, completing the program in four years. Puyuma society was going through great changes then. The Japanese were carrying out their “five-year plan to govern the savages,” altering existing power and societal structures, while more Han Taiwanese began moving to the area. In 1929, the Japanese moved the settlement to its current location, where it’s known today as Nanwang Village (南王).

BaLiwakes wanted to continue studying, but his father was against it as he didn’t think his son’s body could hold up walking daily from the village to Taitung City. The family was also poor, and needed him to help graze the buffalo.

Photo courtesy of National Taitung Living Art Center

He spent the next three years as a cowherd, learning traditional knowledge and skills such as hunting and foraging for wild vegetables. At the age of 12, he entered the takuban communal house where boys learned the ways of the Puyuma.

Meanwhile, a public school was offering classes for students who wanted to pass the secondary school exams. BaLiwakes would tie his buffaloes in a pasture near the school, attend classes and graze them during breaks. He and his sister would also pick wild vegetables that grew in their fields and sell them in Taitung City to raise money for tuition. His father eventually relented.

TRULY FROM TAIWAN

BaLiwakes graduated in 1927, and along with the principal’s son were the only candidates from Taitung to be accepted to Tainan Normal School. BaLiwakes was the only indigenous student in his class.

Here the previously weak boy excelled at both sports and music, especially the piano. His talent was evident as just seven months into the school year, he was chosen to perform for Prince Yasuhiko Asaka, the emperor’s uncle.

Before his performance, the principal announced, “He is not Japanese nor Han. He’s a person truly from Taiwan, and his ability is higher than the average person. He is BaLiwakes.”

After graduating, BaLiwakes taught at several indigenous Amis communities along Taitung’s coast. He had embraced the Japanese lifestyle by then, even becoming certified as a “national language household” that primarily communicated in Japanese.

During World War II, countless indigenous youth joined the war as part of the Takasago Volunteers (not all were true volunteers as many were tricked or forced to go). The women in the villages often sang songs yearning for their loved ones, providing future inspiration for BaLiwakes.

However, his progress fitting into mainstream society was reset to zero as the war ended.

CROSS-CULTURAL POPULARITY

Through an introduction, BaLiwakes landed a job at today’s National Taitung Junior College teaching music and sports, subjects that did not require too much Mandarin. Other indigenous teachers were not as fortunate, retiring early due to language issues.

Paelabang writes that some turned to preserving their fading culture, some devoted themselves to religion and others became depressed, dying of grief or drowning their sorrows in alcohol. BaLiwakes taught until retiring in 1962.

Unlike the indigenous intellectuals who fell victim to White Terror, Paelabang writes that BaLiwakes took an “aggressively defensive” stance, “weaving a ‘safety net’ with his musical talent to calm the uneasy, worried souls of his people.”

This is when he began writing Puyuma songs, mostly about daily life in the village.

BuLai naniyam kaLaLumayan (Beautiful Rice Grain), later made famous by folk legend Ara Kimbo, was written for the Puyuma who were fighting the Chinese Communists in Kinmen during the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis of 1958.

BaLiwakes’ songs were immensely popular among the Puyuma, and some, such as kasare’eDan i kababuTulan (Memories of Orchid Island) were also beloved by the Amis and Paiwan, who adapted the song using their language and musical traditions. Many of his songs have strong Amis flavors, writes Tsai, perhaps due to the time he spent teaching in their villages, and also contain elements of Japanese folk songs and military marches as well as Bunun melodies.

BaLiwakes rarely wrote in Mandarin; a rare example is a 1968 tune celebrating the return of victorious Hongye youth baseball team. Since the members were all indigenous Bunun, he based it on a Bunun melody and added interjections in the language.

SONGS OF FAITH

Life wasn’t easy after retirement; BaLiwakes still had a family to support and he wasn’t used to farm work. Han Taiwanese who moved into the area often took advantage of the indigenous who didn’t know Mandarin or the laws. His family, for example, unwittingly borrowed money from a loan shark to pay medical bills, plunging them into debt that they had to work continuously to pay off.

On Christmas eve, 1971, BaLiwakes was baptized by priest Hans Huser of the Nanwang Catholic Church in his home village, after that most of his compositions were church-related.

One of Huser’s tasks was to “localize” the worship material, which at that point was all in Classical Chinese. BaLiwakes wrote countless hymns in Puyuma for the church, a few were based on traditional tunes. Many are still sung in the church today.

BaLiwakes died while visiting his son in Taipei on March 22, 1988. On the white board at his home was a newly finished song about someone who was working away from home and did not have time to take part in the village’s annual festivities.

“BaLiwakes never left behind any impassioned words of defiance. Instead, in those times where people were silenced, he used music as his language. If we follow the voice of the singing, we can still hear his response to those times,” Tsai writes.

Taiwan is one of the world’s greatest per-capita consumers of seafood. Whereas the average human is thought to eat around 20kg of seafood per year, each Taiwanese gets through 27kg to 35kg of ocean delicacies annually, depending on which source you find most credible. Given the ubiquity of dishes like oyster omelet (蚵仔煎) and milkfish soup (虱目魚湯), the higher estimate may well be correct. By global standards, let alone local consumption patterns, I’m not much of a seafood fan. It’s not just a matter of taste, although that’s part of it. What I’ve read about the environmental impact of the

It is jarring how differently Taiwan’s politics is portrayed in the international press compared to the local Chinese-language press. Viewed from abroad, Taiwan is seen as a geopolitical hotspot, or “The Most Dangerous Place on Earth,” as the Economist once blazoned across their cover. Meanwhile, tasked with facing down those existential threats, Taiwan’s leaders are dying their hair pink. These include former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), Vice President Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) and Kaohsiung Mayor Chen Chi-mai (陳其邁), among others. They are demonstrating what big fans they are of South Korean K-pop sensations Blackpink ahead of their concerts this weekend in Kaohsiung.

The captain of the giant Royal Navy battleship called his officers together to give them a first morsel of one of World War II’s most closely guarded secrets: Prepare yourselves, he said, for “an extremely important task.” “Speculations abound,” one of the officers wrote in his diary that day — June 2, 1944. “Some say a second front, some say we are to escort the Soviets, or doing something else around Iceland. No one is allowed ashore.” The secret was D-Day — the June 6, 1944, invasion of Nazi-occupied France with the world’s largest-ever sea, land and air armada. It punctured Adolf

The first Monopoly set I ever owned was the one everyone had — the classic edition with Mr Monopoly on the box. I bought it as a souvenir on holiday in my 30s. Twenty-five years later, I’ve got thousands of boxes stacked away in a warehouse, four Guinness World Records and have made several TV appearances. When Guinness visited my warehouse last year, they spent a whole day counting my collection. By the end, they confirmed I had 4,379 different sets. That was the fourth time I’d broken the record. There are many variants of Monopoly, and countries and businesses are constantly