A modern form of “grave robbery” is flourishing online, experts say, as bone collectors exploit legal loopholes to buy and sell human remains.

In Australia, where it is illegal to buy or sell human remains (albeit with some exceptions), people sell photographs of the remains then add the bones as a “gift.”

While people may trade in remains to make money, some experts say others with the macabre habit of collecting them do so for power, control and identity.

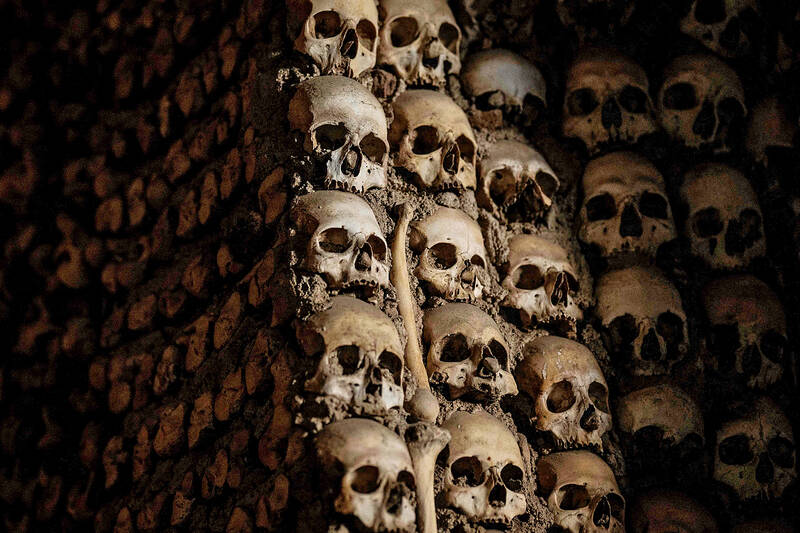

Photo: AFP

BIG BONE COLLECTIONS

Damien Huffer, the author of These Were People Once: The Online Trade in Human Remains and Why It Matters, says some individuals have collections that can rival museums, and Australia’s laws are not sufficient to stop them.

“The laws are quite inconsistent from the state and territory level, and certainly in between countries,” he says.

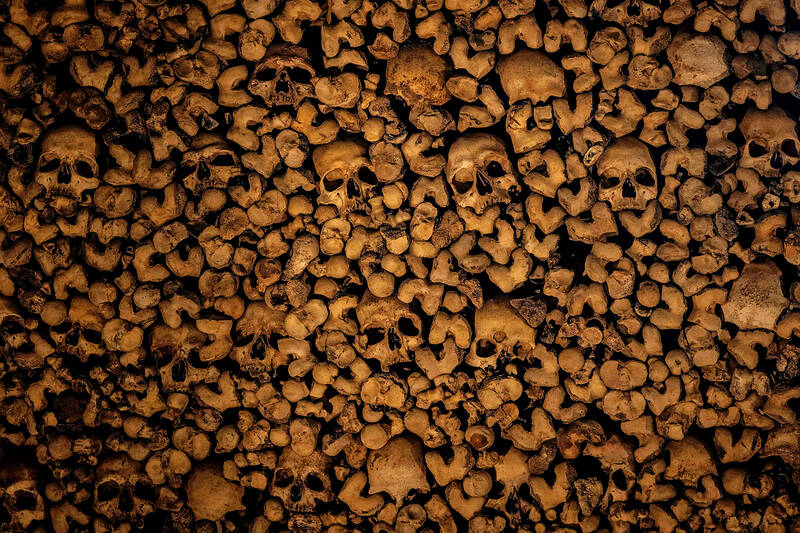

Photo: AFP

“And now so much is online — [it] could have been a very niche little subculture of the antiquities trade if the Internet never existed, but because of the way the world works, what once was niche has blown up.”

Huffer, an honorary research fellow at the University of Queensland and co-founder of the Alliance to Counter Crime Online, has studied an Australia-specific tactic, where photographs of human remains are offered for sale with the bones included as a “gift” to get around laws about buying and selling.

Bone traders also use emojis, codewords and hashtags to connect with each other and evade detection.

Photo: AP

They might discuss “oddities” that are “hooman,” for example. In a paper published in the Journal of Computer Applications in Archaeology, Huffer describes one person posting: “Would someone gift (wink emoji) … a man/woman femur or two?”

Another says: “Oddlings! I have something … special available. You will receive the photo plus a free vintage medical specimen … real (bone emoji). (Ship emoji) inc. payment plans available.”

And it’s not just skeletal remains. Cremains — bone fragments left over after a body is cremated — and wet specimens such as organ slices are also traded.

ILLEGAL

It has been illegal to sell human remains since 1982, when human tissue legislation was rolled out across the states and territories. But many doctors received real skeletons during their training and so collections of bones lingered on, sometimes turning up in sheds and deceased estates.

“Medical” specimens have a kind of legitimacy because many were imported before law changes made importation of human remains illegal and due to limited exemptions for medical items.

Huffer says bones in Australia had often arrived decades ago from India, Bangladesh and elsewhere. He says they were “the unclaimed, the low caste, the poor, who were taken, stripped down, sanitized [and] wired up.”

South Australia police are investigating the alleged sale of human skulls by auctioneers Small and Whitfield: one “medical skull” sold for US$600, another “with open cranium and a few vertebrae” and the “lower jaw missing” was snapped up for US$1,500.

A police spokesperson said the auction house was cooperating and “to date no offenses have been identified.”

“Determining the origins of all of the remains can be a complex and protracted process,” the spokesperson says.

The managing director at Small and Whitfield, David Kabbani, says they have received about three or four skulls over the past 20 years that weren’t medical specimens.

“We know the difference as auctioneers between a genuine medical piece, a skull used for medical purposes as opposed to something that’s come from nobody and nowhere, that we hand in [to police],” he says.

Asked about the origins of the medical pieces, Kabbani says they come from retired doctors, who were legally provided them as part of their training when it was legal to import them. He says there was plenty of uncertainty about the law as it stands, including among the police.

“On many occasions when we’ve had questions about selling these things, we’ve rung the police to get an answer and they’re unsure,” he says.

Maeghan Toews, an Adelaide Law School lecturer who teaches medical law and ethics says state and territory legislation prohibits buying and selling human tissue, from living and deceased bodies.

“There are exceptions, however, which is where some of the uncertainty arises,” she says.

Toews points to the SA Transplantation and Anatomy Act 1983, which allows the sale or supply of tissue “if the tissue has been subjected to processing or treatment and the sale or supply is made for use, in accordance with the directions of a medical practitioner, for therapeutic, medical or scientific purposes.”

“One point of confusion,” she says, “is what counts as a ‘scientific purpose,’ which is not defined in the act.

“Another point of confusion … is the extent of ‘processing’ that is needed to transform the tissue into sellable goods.

“Finally, while the requirement that the sold tissue be used ‘in accordance with the directions of a medical practitioner’ makes sense for therapeutic and medical uses, whether or not this applies (or should apply) to ‘scientific purposes’ is also unclear.”

The Australian Law Reform Commission started an inquiry into the state and territory laws in August.

The inquiry will perhaps clear up some of these points of confusion, she says.

MACABRE COLLECTOR SUBCULTURE

There is a long history of collecting human parts, as war trophies and in museums in the name of science (often racial science).

Modern day collectors might explain their macabre habits as being out of an appreciation for human biology, or curiosity or because of the gothic aesthetic, Samantha Waite says, but she believes there could be a different reason.

Waite, a former hospice psychotherapist, now runs Taboo Education, which works to demystify death.

She says there are various reasons people get into the bone trade, and often it’s tied up with wanting to prove their identity to, and be accepted by, a specific subculture of collectors.

“A lot of them tend to not interact much with the living, this is their way of telling themselves they’re still interacting with humans,” she says. “And there can be a feeling of power.

“Psychology-wise, specific parts of the body tend to mean certain things and a skull is definitely one of power.”

Huffer says people should think about how they would feel if their loved ones were “taken out of their place of rest, dug up, circulated and recirculated with price tags.”

It’s dehumanizing, and perpetuating colonial violence, he says.

“The bottom line is no one who entered the medical bone trade … none of them ever consented to being used as such,” she says.

“Who knows, [there might be] hundreds of thousand of examples on the market, from the days before consent forms, paperwork – it’s just another form of grave robbery.”

June 9 to June 15 A photo of two men riding trendy high-wheel Penny-Farthing bicycles past a Qing Dynasty gate aptly captures the essence of Taipei in 1897 — a newly colonized city on the cusp of great change. The Japanese began making significant modifications to the cityscape in 1899, tearing down Qing-era structures, widening boulevards and installing Western-style infrastructure and buildings. The photographer, Minosuke Imamura, only spent a year in Taiwan as a cartographer for the governor-general’s office, but he left behind a treasure trove of 130 images showing life at the onset of Japanese rule, spanning July 1897 to

One of the most important gripes that Taiwanese have about the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is that it has failed to deliver concretely on higher wages, housing prices and other bread-and-butter issues. The parallel complaint is that the DPP cares only about glamor issues, such as removing markers of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) colonialism by renaming them, or what the KMT codes as “de-Sinification.” Once again, as a critical election looms, the DPP is presenting evidence for that charge. The KMT was quick to jump on the recent proposal of the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) to rename roads that symbolize

On the evening of June 1, Control Yuan Secretary-General Lee Chun-yi (李俊俋) apologized and resigned in disgrace. His crime was instructing his driver to use a Control Yuan vehicle to transport his dog to a pet grooming salon. The Control Yuan is the government branch that investigates, audits and impeaches government officials for, among other things, misuse of government funds, so his misuse of a government vehicle was highly inappropriate. If this story were told to anyone living in the golden era of swaggering gangsters, flashy nouveau riche businessmen, and corrupt “black gold” politics of the 1980s and 1990s, they would have laughed.

In an interview posted online by United Daily News (UDN) on May 26, current Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) was asked about Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕) replacing him as party chair. Though not yet officially running, by the customs of Taiwan politics, Lu has been signalling she is both running for party chair and to be the party’s 2028 presidential candidate. She told an international media outlet that she was considering a run. She also gave a speech in Keelung on national priorities and foreign affairs. For details, see the May 23 edition of this column,