May 27 to June 2

A man surnamed Tsou (鄒) was riding in the second to last carriage when terrified passengers began rushing in from the front of the train. A fire had broken out a few cars ahead, they said.

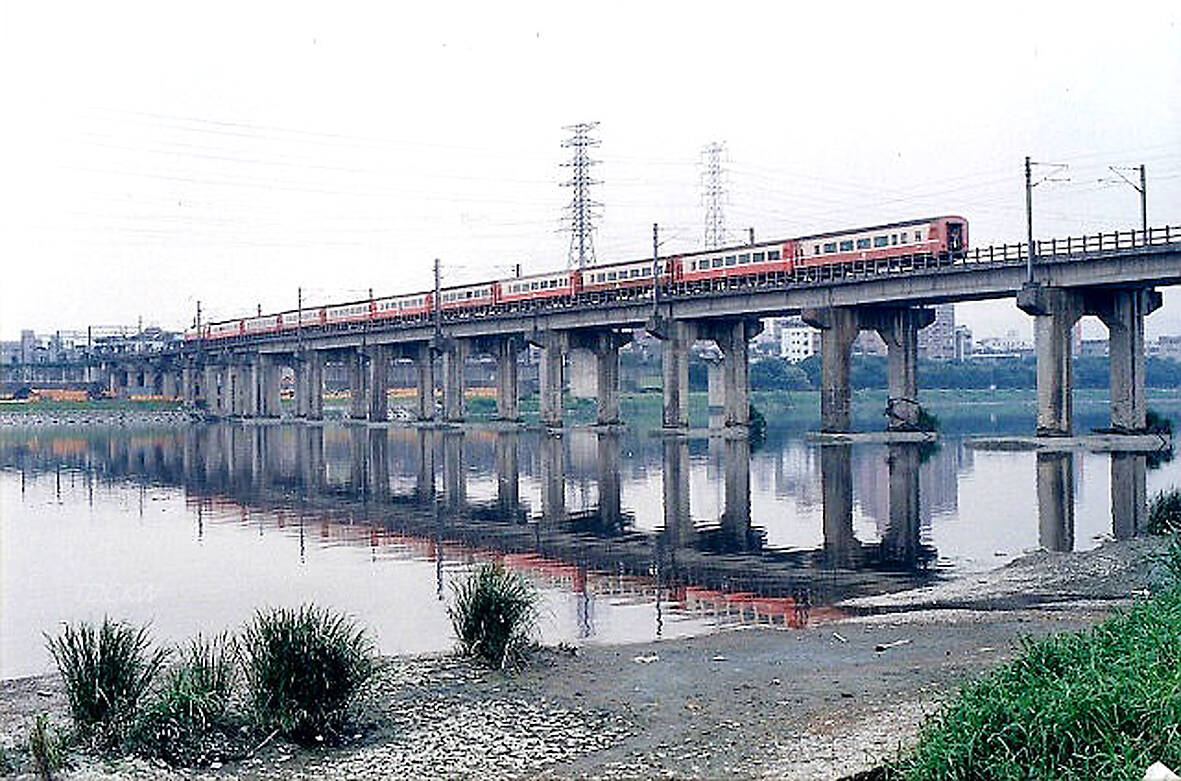

As Tsou pushed his way to the last car, the southbound train came to a halt atop the Sindian River Bridge (新店溪橋). He saw people jumping off the train into the river and sandbanks below.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Tsou did not jump; he and a group of passengers managed to exit from the tail of the train, walking over the tracks on the bridge to safety. The train then detached the burning carriages and continued forward, leaving behind four completely charred cars.

While the official death count was 21, an additional 43 missing passengers were presumed dead, making the May 28, 1948 event the most lethal train accident in Taiwanese history. The cause is believed to be passengers either bringing camphor powder or gasoline onto the train, and it didn’t help that the fire broke out on a bridge with little space to evacuate.

Donations for the victims and their families poured in over the following week, and the Taiwan Railways Administration also offered compensation. Tsou visited the Public Opinion Press (公論報) office the following day to contribute to their fundraiser, and also sat down to provide his first-hand account of the events. He reportedly gave them all the money he had on him, telling them to give half to the dead and half to the wounded.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

SAFETY ISSUES

Prior to the Sindian River Bridge accident, the worst train accident in Taiwan happened on June 21, 1918, as a southbound train ascended a steep slope between Yingge (鶯歌) and Taoyuan stations. A train connector snapped, hurtling loose carriages down the hill all the way back to Yingge Station. Most reports show 13 dead and hundreds injured. This spurred the Japanese colonial government to move the station and rebuild the tracks using a gentler circular slope. Completed in 1922, the new route is still in use today.

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) took over the railway system when it arrived in 1945. At first, the newcomers worked alongside the Japanese and Taiwanese staff, but most Japanese had been sent home by the end of 1947.

In March 1948, the Railway Administration Council was upgraded to the Taiwan Railways Administration. Wen Wen-yu (溫文佑) writes in Study on Taiwan’s post-war railway history (戰後台灣鐵路史之研究) that one of the things the first chief, Lang Chung-lai (郎鍾騋), did was to establish a Traffic Safety Committee and promulgate comprehensive rules for disaster preparation and response. Lang noted that although accidents and malfunctions were frequent, they were mostly due to human error and could be prevented through stricter enforcement.

A particularly pesky issue was children stacking rocks on the tracks. This had been a problem since the Japanese era, Wen writes, but there were seven incidents due to this behavior in 1949 alone. On Dec. 9, 1957, a group of five and six year olds were playing on the tracks near Yingge, and the stones they left behind caused a serious derailment that killed 18 and injured more than 100.

TRAGEDY STRIKES

There was already a close call with a fire just 16 days before the Sindian River Bridge incident. The southbound train had just left Taipei station when someone accidentally spilled lighter fluid onto a pile of woven rush hats. The rims of these hats were supported with highly flammable film stock, which burst into flames. Fortunately the fire was put out quickly and nobody was hurt. The TRA subsequently banned such hats onboard.

Initial reports from the Public Opinion Press (公論報) show complete chaos on the train as the fire spread. There were about 300 people crammed into the affected carriages, and panic ensued as everyone clamored to escape.

Even before the train stopped, people began jumping out the windows into the river, and many drowned. Others were stuck in the crowd and burned alive.

TRA personnel soon arrived to remove the wreckage and retrieve bodies from the river. The exact cause of the fire remained under investigation for weeks, but the May 30 edition of the newspaper surmised that it was camphor powder or oil that ignited. Witnesses recall the smell of “burning celluloid,” which is partially made of camphor.

AFTERMATH

In a letter to the editor, a reader criticized the TRA’s enforcement efforts, saying that they spent more resources going after illegal vendors selling snacks on board instead of thoroughly checking for dangerous items.

Taoist memorials to transmute the souls of the dead were held on both sides of the river the following month, and dragon boat races were held alongside other performances.

In the ensuing months the TRA posted notices in all stations regarding dangerous substances and urged all staff to be vigilant in checking passenger luggage. It also began rewarding passengers who successfully reported any suspicious materials or behavior.

Firefighting equipment in the carriages were upgraded with all staff undergoing training. The TRA held regular safety competitions and rewarded workers for accident-free periods of varying duration.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name