Le Van Tam is no stranger to how the vagaries of global trade can determine the fortunes of small coffee farmers like him.

He first planted coffee in a patch of land outside Buon Ma Thuot city in Vietnam’s Central Highland region in 1995. For years, his focus was on quantity, not quality. Tam used ample amounts of fertilizer and pesticides to boost his yields, and global prices determined how well he did.

Then, in 2019, he teamed up with Le Dinh Tu of Aeroco Coffee, an organic exporter to Europe and the US, and adopted more sustainable methods, turning his coffee plantation (field) into a sun-dappled forest. The coffee grows side-by-side with tamarind trees that add nitrogen to the soil and provide support for black pepper vines. Grass helps keep the soil moist and the mix of plants discourages pest outbreaks. The pepper also adds to Tam’s income.

Photo: AP

“The output hasn’t increased, but the product’s value has,” he said.

BEAN BOOM

In the 1990s, Tam was among thousands of Vietnamese farmers who planted more than a million hectares of coffee, mostly robusta, to take advantage of high global prices. By 2000, Vietnam had become the second-largest producer of coffee, which provides a tenth of its export income.

Photo: AP

Vietnam is hoping that farmers like Tam will benefit from a potential reordering of how coffee is traded due to more stringent European laws to stop deforestation.

The European Deforestation Regulation or EUDR will outlaw sales of products like coffee from Dec. 30 if companies can’t prove they are not linked with deforestation. The new rules don’t just seek to reduce risks of illegal logging and its scope is wide: It will apply to cocoa, coffee, soy, palm oil, wood, rubber, and cattle. To sell those products in Europe, big companies will have to provide evidence showing they come from land where forests haven’t been cut since 2020. Smaller companies have till July 2025 to do so.

Deforestation is the second-biggest source of carbon emissions after fossil fuels. Europe ranked second behind China in the amount of deforestation caused by its imports in 2017, according to a 2021 World Wildlife Fund report. If implemented well, the EUDR could help reduce this, especially if the more stringent standards for tracing where products come from becomes the “new normal,” said Helen Bellfield, a policy director at Global Canopy.

It’s not failsafe. Companies can just sell products that don’t meet the new requirements elsewhere, without reducing deforestation. Thousands of small farmers unable to provide the potentially expensive data could be left out. Much depends on how countries and companies react to the new laws, Bellfield said. Countries must help smaller farmers by building national systems ensure their exports are traceable. Otherwise, companies may just buy from very large farms that can prove they have complied.

Already, orders for Ethiopian grown coffee have fallen. And Peru lacks the capacity to provide information needed for coffee and cocoa grown in the Peruvian Amazon.

This is on top of other challenges, which in Vietnam include worsening droughts and receding ground water levels.

“There will be winners and losers,” she said.

MARKETS MATTER

Vietnam can’t afford to lose — Europe is the largest market for its coffee, comprising 40 percent of its coffee exports. Six weeks after the EUDR was approved, Vietnam’s agriculture ministry started working to prepare coffee growing provinces for the shift. It has since rolled out a national plan that includes a database of where crops are grown and mechanisms to make this information traceable.

The Southeast Asian nation has long promoted more sustainable farming, viewing laws like the EUDR as an “an inevitable change,” according to agriculture ministry communique from August last year. The EUDR could help accelerate such a transformation, according to agriculture minister Le Minh Hoang.

Tam and Tu, his export partner, were quick to adapt.

Even if the costs are higher, Tu said, they can get better prices for their high quality coffee

“We must choose the highest quality. Otherwise, we will always be laborers,” Tu said, while sipping a cup of his favorite coffee at his company’s coffee processing factory adjoining Tam’s farm. This is where trucks laden with red coffee cherries, both robusta and arabica, arrive from other farms, where the pulp of the fruit removed and beans of coffee laid out on tables to dry in the sun.

Tu already has certificates from international agencies for sustainability that will enable him to deal with the EUDR. Such certificates typically address the issue of deforestation, although some tweaks may be needed, said David Hadley, program director for regulatory impacts at the non-profit group Preferred by Nature in Costa Rica.

Ensuring that Vietnam’s roughly half a million small farmers, who produce about 85 percent of its coffee, are able to collect and provide data showing their farms did not cause deforestation remains a challenge. Some may struggle to use smartphones to collect geolocation coordinates. Small exporters need to set up systems to prevent other uncertified products from being mixed with coffee that meets EUDR requirements, said Loan Le of International Economics Consulting.

Farmers also will need documents proving they have complied with national laws for land use, environmental protection and labor, Le said. Moreover, coffee’s long value chain — from producing beans to collecting them and processing them — requires digital systems to ensure records are error-free.

Brazil, the world’s largest coffee producer, is better placed, said Bellfield of Global Canopy, since its coffee grows on plantations that are away from forests and it has a relatively well organized supply chain. Also, Brazilian-grown coffee is most likely to meet the EUDR requirements, according to a Brazilian study this year, because much of it is exported to the EU, Brazil has fewer small farmers, and about a third of its coffee growing acreage already has some kind of sustainability certification.

The EUDR has acknowledged concerns for less well prepared suppliers by giving them more time and said the European government will work with impacted countries to “enable the transition” while “paying particular attention” to the needs of small holders and Indigenous communities. A review in 2028 will also look at impacts on smallholders.“Despite this we still anticipate it being costly and difficult for small holder farming communities,” said Bellfield.

In Peru, collecting information about hundreds of thousands of small farmers is difficult given the country’s weak institutions and the fact that most farmers lack land titles, according to a study of EUDR impacts by the Amazon Business Alliance, a joint-initiative by USAID, Canada and the nonprofit group Conservation International.

Ethiopia, where coffee makes up about a third of total export earnings according to a US Department of Agriculture report, has been slow to react. The national plan it rolled out in February this year fails to resolve the fundamental issue of how to gather required data from millions of small farmers and provide that information to buyers, said Gizat Worku, head of the Ethiopian Coffee Exporters Association.

“That requires a huge amount of resources,” he said

Gizat, who like many Ethiopians goes by his first name, said that orders are falling due to doubts about the country’s ability to comply with the EUDR. Some traders are contemplating switching to other markets, like the Middle East or China, where Ethiopian coffee is “booming,” he said. But switching markets isn’t easy.

“These regulations are going to have a tremendous impact,” Gizat said.

When life gives you trees, make paper. That was one of the first thoughts to cross my mind as I explored what’s now called Chung Hsing Cultural and Creative Park (中興文化創意園區, CHCCP) in Yilan County’s Wujie Township (五結). Northeast Taiwan boasts an abundance of forest resources. Yilan County is home to both Taipingshan National Forest Recreation Area (太平山國家森林遊樂區) — by far the largest reserve of its kind in the country — and Makauy Ecological Park (馬告生態園區, see “Towering trees and a tranquil lake” in the May 13, 2022 edition of this newspaper). So it was inevitable that industrial-scale paper making would

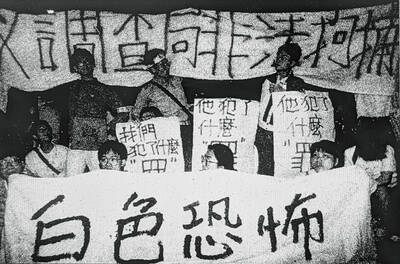

July 21 to July 27 If the “Taiwan Independence Association” (TIA) incident had happened four years earlier, it probably wouldn’t have caused much of an uproar. But the arrest of four young suspected independence activists in the early hours of May 9, 1991, sparked outrage, with many denouncing it as a return to the White Terror — a time when anyone could be detained for suspected seditious activity. Not only had martial law been lifted in 1987, just days earlier on May 1, the government had abolished the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of National Mobilization for Suppression of the Communist

Hualien lawmaker Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) is the prime target of the recall campaigns. They want to bring him and everything he represents crashing down. This is an existential test for Fu and a critical symbolic test for the campaigners. It is also a crucial test for both the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a personal one for party Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫). Why is Fu such a lightning rod? LOCAL LORD At the dawn of the 2020s, Fu, running as an independent candidate, beat incumbent Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmaker Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) and a KMT candidate to return to the legislature representing

Asked to define sex, most people will say it means penetration and anything else is just “foreplay,” says Kate Moyle, a psychosexual and relationship therapist, and author of The Science of Sex. “This pedestals intercourse as ‘real sex’ and other sexual acts as something done before penetration rather than as deserving credit in their own right,” she says. Lesbian, bisexual and gay people tend to have a broader definition. Sex education historically revolved around reproduction (therefore penetration), which is just one of hundreds of reasons people have sex. If you think of penetration as the sex you “should” be having, you might