Sept. 11 to Sept.17

More than 5,000 visitors flocked to Yangmingshan on Sept 11, 1999 to get a glimpse of what many called former president Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石) “final residence.” Although it wasn’t where Chiang spent his last days, it was the last of his numerous abodes across Taiwan to be built, and also the most spacious.

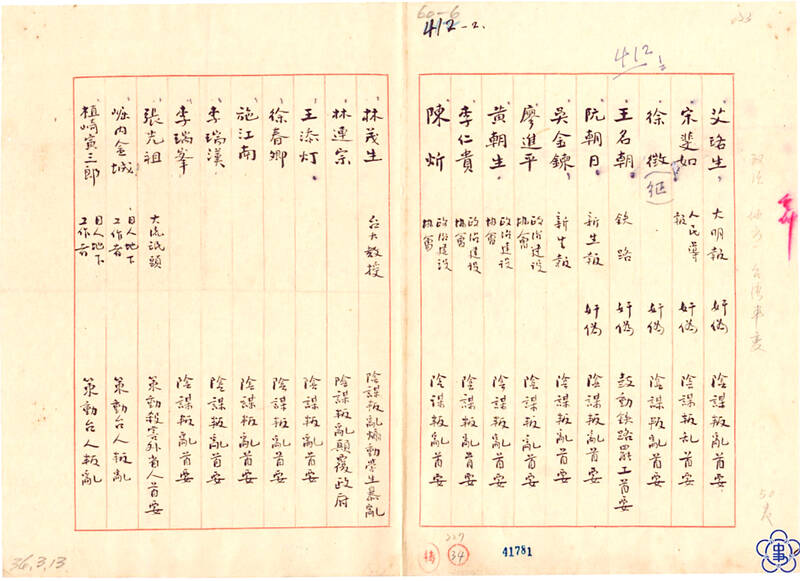

Like many Chiang residences, the highlight on the news was the secret underground tunnel that he would use in case of emergency. The “Daxi Files” (大溪檔案), consisting of more than 270,000 documents, letters and photos tied to or created by Chiang between 1925 and 1975, were stored underground here until they were handed over to Academia Historica in the 1990s.

Photo courtesy of Academia Historica

Named the Zhongxing Guesthouse (中興賓館), this complex was completed in 1970, just four years before Chiang’s death. Chiang was fond of Yangmingshan; he stayed there when he first arrived in Taiwan and spent many summers at the Grass Mountain Chateau (草山行館), originally a recreational center and guesthouse built by the Taiwan Sugar Corporation in 1920.

Zhongxing Guesthouse was meant to serve as a new summer home for the president, where he would also receive foreign dignitaries. Chiang did not get to enjoy it for long, however, as he was hospitalized with a serious bout of pneumonia in July 1972. He shuttled between the Taipei Veterans General Hospital and his main residence in Taipei’s Shilin District (士林) until his death in April 1975, never returning to his beloved mountain villa.

The structure remained empty for four years, upon which it became Yangming Shuwu (陽明書屋), the headquarters and storage for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) Party History Institute. The entire property was handed over to Yangmingshan National Park in 1997, and soon became a tourist attraction.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

GRASS MOUNTAIN CHATEAU

Chiang was well-acquainted with Yangmingshan before he retreated to Taiwan from China in 1949. In June of that year, he stayed at the mountain, and on one of his walks he discovered the empty Grass Mountain Chateau. He took a great liking to the building and its environs, using it as a living and working space when he returned in October.

With China all but lost to the communists, Chiang left his homeland for good on Dec. 10, 1949, moving into Grass Mountain Chateau upon arrival. He had temporarily stepped down as president, but after he resumed office in March 1950 he needed a place closer to the government agencies in downtown Taipei. On March 31, he moved into the Japanese-built Horticultural Experimental Station, known today as the Shilin Residence (士林官邸). The residence was exceptionally hot during summers, and Chiang, who reportedly eschewed fans and air conditioners, often spent May to September at Grass Mountain Chateau.

Photo: Chen Wei-tzu, Taipei Times

The presence of officialdom on Yangmingshan grew when Zhongshan Hall was completed in 1966. Many government meetings as well as international conferences and gatherings were held there, and in 1972 it became home to the National Assembly.

While spending his summers on Yangmingshan, Chiang enjoyed walking in the woods where the guesthouse was to be built. The views from there, like many places in Taiwan, reminded him of his hometown in Fenghua County, Zhejiang Province.

The Grass Mountain Chateau was hard to maintain as a historic structure and was running out of space, so in the late 1960s, the Chiangs decided to build a new residence. The Veteran Affairs Council’s RSEA Engineering Corporation was in charge of construction under a “special permit,” supervised by Chiang’s grandson Chiang Hsiao-yung (蔣孝勇). The architect of the Chinese garden style structure was Huang Pao-yu (黃寶瑜), designer of the National Palace Museum. Most laborers were veterans from China.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Chiang often personally inspected the construction, and in 1969 he was involved in a car accident on Yangde Boulevard (仰德大道) leading to the mountain, which greatly affected his health. He wrote in his diary that the accident caused him to lose 20 years of his life, though he was already 82 years then.

HISTORICAL ARCHIVES

Zhongxing Guesthouse’s main building was finished in May 1970, while the other structures and gardens were completed over the year. It was breezy and spacious, but also suffered from humidity by being sandwiched between two peaks. Chiang’s personal doctor Hsiung Wan (熊丸) disliked the wind, however, saying that it sounded terrifying at night and attributed Chiang’s rapid decline in health to the structure’s bad fengshui.

Chiang spent the summer of 1971 living and working from the guesthouse, and he was staying there in July 1972 when he fell ill. Soong Mayling (宋美齡), known to much of the world as Madame Chiang Kai-shek, and relatives visited occasionally while Chiang recovered, but activity at the compound decreased after his death.

Locals recall still seeing military police guard the residence over the ensuing years, adding to its mystique. In 1979, Chiang’s son Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) decided to move the Party History Institute into the building, transporting the KMT history archives and the Daxi Documents from Nantou and Taoyuan, respectively.

Institute director Chin Hsiao-yi (秦孝儀) rechristened the place Yangming Shuwu (“Yangming archives”) and engraved it on a new plaque in front. The exterior of the buildings remained unchanged, but the interiors were all repurposed, with the main structure serving as a memorial hall to Chiang, KMT founder Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙) and other important figures in party history. The Daxi Documents were stored below this building and were off limits — even to staff members without special permission.

A three-story building was erected to keep the other documents, while Party History Institute staff worked from auxiliary spaces such as the former security guard living quarters.

Few visited at first, but long-time employee Chen Li-wen (陳立文) recalls in a Yangmingshan National Park study on the residence that students, scholars and local officials began showing up starting around 1984 for research or touring purposes. Former Singaporean prime minister Lee Kuan Yew (李光耀) visited in 1986.

The compound remained guarded and off limits to the public until the lifting of martial law in 1987 led to demands to open it up. In 1991, Zhongxing Road (中興路, dubbed the “President’s Road”) began allowing civilian traffic. By 1992, only the main structure remained guarded by plainclothes officers.

In 1993, the Lee family (李), who owned more than half of the 14-hectares of land the compound sat on, wanted their property back. After three years of negotiations, the government decided to give the buildings to the national park and buy the rest of the land from the Lees.

The Party History Institute held a bash at the residence for its 65th anniversary in 1995, and in 1998 it relocated to then-party headquarters on Zhongshan S Road.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades