The bodycam footage of police shooting undocumented Vietnamese migrant worker Nguyen Quoc Phi nine times isn’t the most harrowing scene in And Miles to go Before I Sleep (九槍) — it’s the ensuing moments, which feels like a suffocating eternity, where Nguyen is left naked on the ground to bleed out.

An ambulance arrives and inexplicably takes a person who was punched in the nose by Nguyen to the hospital first, while officer Chen Chung-wen (陳崇文) repeatedly tells those at the scene not to approach the seriously injured Nguyen because he’s dangerous.

This controversial case from 2017 touches upon numerous topics, from appropriate use of police force to migrant worker mistreatment and racism. Nguyen, who was allegedly on drugs, refused to comply with police and attempted to steal a patrol car. He later succumbed to his wounds, while Chen was convicted of negligent manslaughter. He avoided jail time and settled with Nguyen’s family out of court. Meanwhile, the Hsinchu County Police Bureau was censured for “inadequate training” leading to the use of excessive force, delay in getting medical help and tampering with crime scene evidence.

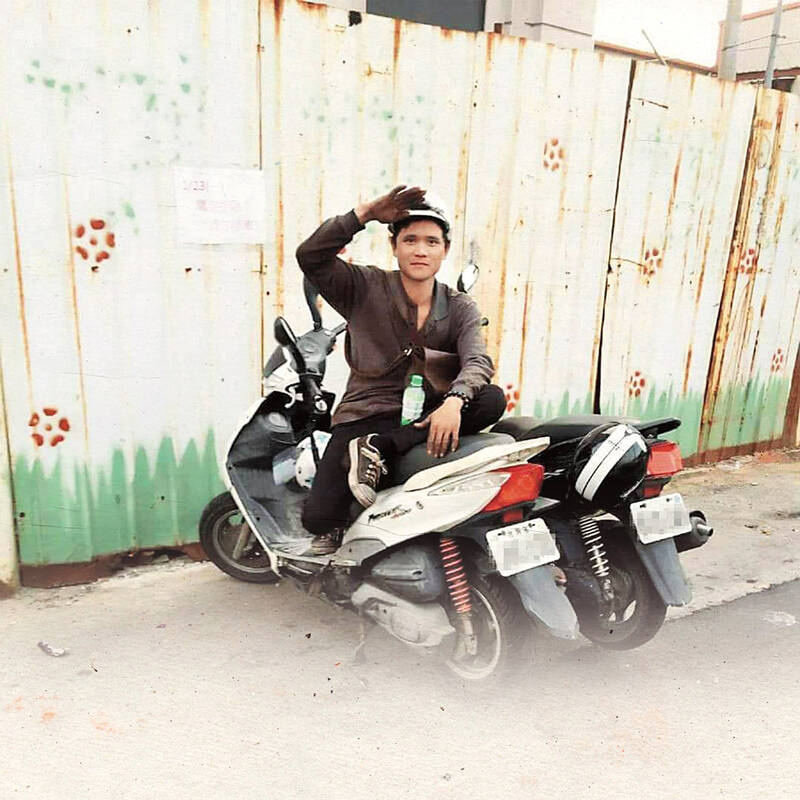

Photo courtesy of And Miles to go Before I Sleep

Both sides have their supporters. Chen reportedly already used pepper spray and his baton on Nguyen before pulling his firearm, and police reluctance to use their guns for fear of such repercussions has been a point of contention whenever an officer is killed by a suspect. To Chen’s family and advocates, Nguyen was a drug-addicted criminal who attacked first, and Chen should not be punished for simply for doing his job.

This perspective is only slightly touched upon in the film, as it mostly avoids getting into the argument of who’s right or wrong. The shooting mostly serves as a vehicle to humanize Nguyen and explain the complicated circumstances that drove him and countless others to desperation.

As director Tsai Tsung-lung (蔡崇隆) said in an interview: “What killed Nguyen Quoc Phi wasn’t merely those nine shots.”

Photo courtesy of And Miles to go Before I Sleep

Tsai interviews Nguyen’s family in Vietnam, speaks to his coworkers in Taiwan and intersperses emotional excerpts from Nguyen’s Facebook posts about his hardships in Taiwan, his hopes for the future and his yearning for his family. Context is provided through interviews with lawyers, brokers and agencies involved in the hiring of migrant workers, as well as scenes of the various incidents and tragedies involving migrant workers over the years, as well as protests held against their exploitation and abuse.

Mixing calm, atmospheric shots with interviews and news footage, And Miles to go Before I Sleep weaves together a sympathetic, but not overly sentimental portrait of Nguyen and others who have suffered similar fates. These workers don’t run away for no reason. In Nguyen’s case he was ripped off by his broker and paid significantly less than promised, leading him to flee for better opportunities. Tsai doesn’t go into detail, but provides just enough context to give the viewer a general idea of the issue.

One element that’s largely missing is a discussion about racism toward Southeast Asians. For example, how did it play a part in the police’s seemingly callous actions, especially after the shooting? Endemic discrimination toward migrant workers are briefly mentioned, but the viewers are left to draw their own conclusions.

Photo courtesy of And Miles to go Before I Sleep

Chen’s conviction doesn’t change the fact that there are still more than 80,000 undocumented migrant workers in Taiwan living under often hazardous and abusive conditions. Like the experts in the film say, major systemic changes are needed, but that has been slow to happen.

Regardless of whether discrimination played a role in the actions of the police, the ongoing debate over appropriate gun use among Taiwanese police officers is also worth exploring, especially after the killing of two officers last August. But that’s a topic for another documentary.

June 9 to June 15 A photo of two men riding trendy high-wheel Penny-Farthing bicycles past a Qing Dynasty gate aptly captures the essence of Taipei in 1897 — a newly colonized city on the cusp of great change. The Japanese began making significant modifications to the cityscape in 1899, tearing down Qing-era structures, widening boulevards and installing Western-style infrastructure and buildings. The photographer, Minosuke Imamura, only spent a year in Taiwan as a cartographer for the governor-general’s office, but he left behind a treasure trove of 130 images showing life at the onset of Japanese rule, spanning July 1897 to

One of the most important gripes that Taiwanese have about the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is that it has failed to deliver concretely on higher wages, housing prices and other bread-and-butter issues. The parallel complaint is that the DPP cares only about glamor issues, such as removing markers of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) colonialism by renaming them, or what the KMT codes as “de-Sinification.” Once again, as a critical election looms, the DPP is presenting evidence for that charge. The KMT was quick to jump on the recent proposal of the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) to rename roads that symbolize

On the evening of June 1, Control Yuan Secretary-General Lee Chun-yi (李俊俋) apologized and resigned in disgrace. His crime was instructing his driver to use a Control Yuan vehicle to transport his dog to a pet grooming salon. The Control Yuan is the government branch that investigates, audits and impeaches government officials for, among other things, misuse of government funds, so his misuse of a government vehicle was highly inappropriate. If this story were told to anyone living in the golden era of swaggering gangsters, flashy nouveau riche businessmen, and corrupt “black gold” politics of the 1980s and 1990s, they would have laughed.

It was just before 6am on a sunny November morning and I could hardly contain my excitement as I arrived at the wharf where I would catch the boat to one of Penghu’s most difficult-to-access islands, a trip that had been on my list for nearly a decade. Little did I know, my dream would soon be crushed. Unsure about which boat was heading to Huayu (花嶼), I found someone who appeared to be a local and asked if this was the right place to wait. “Oh, the boat to Huayu’s been canceled today,” she told me. I couldn’t believe my ears. Surely,