Alone, exhausted, dehydrated, out of water, scratched from head to toe and faced with so much uncertainty ahead, I collapsed onto the forest floor, utterly defeated. It was the most demoralizing moment of my hiking career in Taiwan. With at least five more days remaining until I reached the summit of Jade Mountain, I contemplated giving up. Surely that was the safest thing to do, and perhaps the sanest decision I could make on this less-than-sane excursion.

As Taiwan’s highest peak, Jade Mountain (玉山) is of course a very popular summit among seasoned and newbie hikers. It is normally done as a two-day hike that presents few of the problems mentioned above. With many mountains in Taiwan, there are multiple ways of reaching a summit. There is the tried-and-tested route, well trodden and well documented. There may be alternative “back door” routes, poorly maintained and less trafficked. And then there may be other routes that only someone who is bored with the existing options or someone with a few screws loose would ever dream up.

For instance, after completing the 100 Peaks of Taiwan, some hikers go on to attempt the Central Mountain Traverse, where they re-hike all of the Central Mountain Range Sections and the gaps between them: a grueling month-long journey starting near the border of Yilan County and ending down in Kaohsiung. Others choose to explore old cross-island routes from the Qing and Japanese eras or long-abandoned logging areas. For this trip, my idea was to start at the very bottom — where the Jade Mountain Range first rises up from the plains in Kaohsiung — and then follow that ridge all the way to the top.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

HARD GOING

The very beginning and the very top of this ridge have well established trails. Everything in between is not well traveled, with information on some sections seemingly absent from the entire Internet. Initial research and planning seemed to indicate this 140km journey would take 10 to 14 days, and would require several caches of food and especially water if I was to complete it all in one go. By staying on or near top of the ridge, I would not be crossing any streams to use as drinking water.

It became clear right away that so many things would have to come together perfectly for this to work. The weather would have to be decent for nearly two straight weeks. The food and water I cached would have to remain undisturbed by animals for nearly two weeks. There would have to be no major landslides in the way. There could be no section with cliffs on three sides that made navigation impossible.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

As it turned out, many of these fears were warranted, and there were more hazards that I hadn’t anticipated. Hiking in Taiwan is challenging enough on established trails; step off the beaten track and you may be in for a world of hurt.

The first three days were almost all under 1,000m in elevation. I made great time as I was able to piece together existing trails and old farm roads to stay near the top of the ridge with minimal bushwhacking. Interesting sights along the way included abandoned farmhouses, an old bamboo charcoal kiln, a roadside shrine featuring a natural spring, an old cross-mountain trail that Scottish photographer John Thomson took during his 1871 visit and, of course, the Southern Cross-Island Highway.

This highway and one other farm road before it are the only roads that completely cross over this arm of the Jade Mountain Range. Luckily, there was a temple near the high point of the road where I was able to cache some food, and there was unlimited running water here to quench my already intense thirst. Even in the winter, hiking this low was so much hotter than the high mountains I was used to, and I was sweating profusely, going through far more water than planned — my first mistake.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

LIFE-AND-DEATH DECISIONS

The next three days tested my stamina, heat tolerance and, above all, sanity.

The ridge here was full of old farming roads, but instead of being easy trails, they were so overgrown with low, dense vegetation that the going was painfully slow and, well, painful: sharp-edged silvergrass and thorny brambles ravaged my arms, legs and neck. At one point I had to push through bamboo that was so dense my backpack wouldn’t fit between adjacent stalks, and fallen bamboo blocked the way horizontally at knee, waist and shoulder height. One place was so overgrown it took an hour just to move 200m forward. Later, I chose the wrong fork in the road, kept getting further and further away from the ridge, and ended up having to climb up a bare landslide to regain it as the way forward became too overgrown and steep.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

The only pleasant surprise on this section was the farmer I ran into on Day 4 immediately after cursing my way loudly down a hill thick with silvergrass. Perhaps he’d heard my frustration, or could see the look of exasperation on my face; whatever the reason, he took pity on me and offered me a liter of water, which I immediately downed as I was quickly becoming dehydrated from the constant battle against the vegetation in the heat. This was the last person I saw on the ridge until I neared Jade Mountain.

Finally, on Day 6, everything came to a head. After an hour and a half hacking a tunnel through the grass and low branches with my machete, only to discover a knife-edge ridge covered in three-meter-high silvergrass and a 60 and 80-degree slope on either side, I decided to turn around for the day and find a campsite. It was at that point that I noticed my water bottle had fallen out and I had lost more of that precious liquid resource.

With my next water cache still a day ahead — or perhaps three days, if the vegetation remained as thick as today’s — less than two liters of water remaining, and my body already severely dehydrated, I decided that the wisest decision would be to get out of the mountains. After all, most mountain disasters happen not because one thing went wrong, but because a series of things all went wrong one after another and it’s suddenly too late to back out safely.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

With that, I gave up on the dream of doing the entire hike in one go and decided to return home to recuperate. Weeks of planning were still not enough: the hot weather and dense vegetation had defeated me. A week later, however, I was recharged and ready to continue from where I’d left off.

FINISHING IT OFF

The remaining five days ended up being easier. After passing 2,000m elevation, the vegetation got a little more forgiving, with the heavy canopy and cooler temperatures leaving only sparse undergrowth that was easy to walk through. The cooler temperatures up here also meant I was going through less water now. I was delighted to find my last food and water cache completely untouched, even after two weeks. I passed the last logging road coming up from Kaohsiung villages and climbed up through peaks covered in old-growth forest of Chinese hemlock and Yushan cane bamboo, before finally reaching a forest road going in the opposite direction, towards Nantou County.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

With one final unknown section left, my anxiety reached its peak. Would I be able to make it through this and complete the journey? Or would some unexpected obstacle force me to turn back, so close to the end? I soon came face-to-face with a three-meter wall that I could not scale. A vertical landslide lay to the right, and a steep-walled canyon lay to the left. It appeared to be a dead end. But, after backtracking a short distance, I discovered a very obvious trail on the left. This had been worn into the mountain by animals trying to get around this very same obstacle. I followed this “deer superhighway” around the cliff and was soon back on track.

After I passed South Jade Mountain (南玉山), there was a proper hiking trail to follow. I spent a luxurious night indoors in Yuanfeng Cabin, just below Jade Mountain, and finally reached the summit on the eleventh day of hiking. It did not go quite as planned, as I had to interrupt the hike in the middle, but I had walked the entire ridge from the plains to the summit in 11 days.

Photos: Tyler Cottenie

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

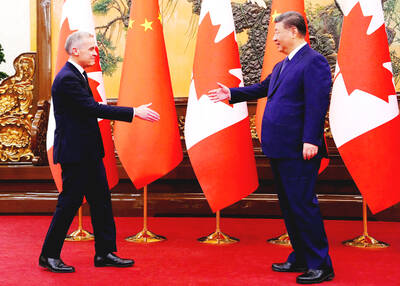

Britain’s Keir Starmer is the latest Western leader to thaw trade ties with China in a shift analysts say is driven by US tariff pressure and unease over US President Donald Trump’s volatile policy playbook. The prime minister’s Beijing visit this week to promote “pragmatic” co-operation comes on the heels of advances from the leaders of Canada, Ireland, France and Finland. Most were making the trip for the first time in years to refresh their partnership with the world’s second-largest economy. “There is a veritable race among European heads of government to meet with (Chinese leader) Xi Jinping (習近平),” said Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, director