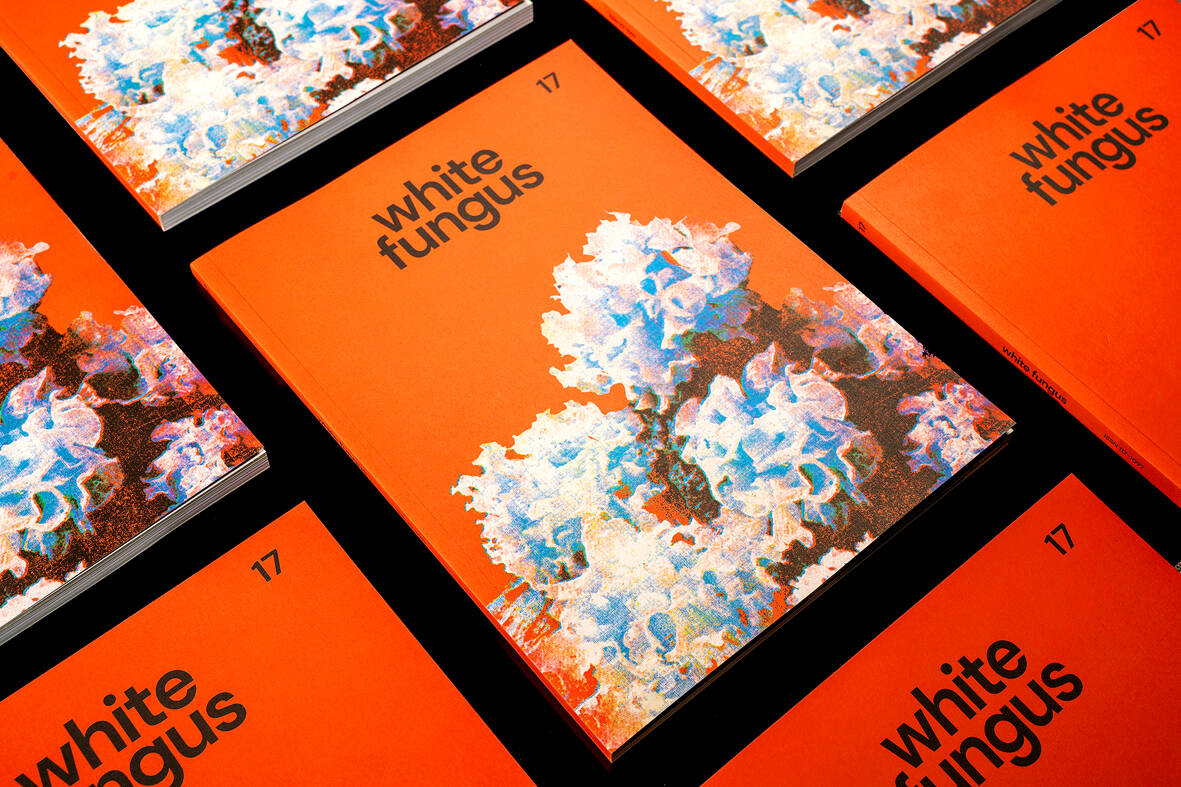

Since its beginnings as a stapled, photocopied protest zine, every cover of White Fungus magazine has shown the same graphic of the titular medicinal ingredient with no description of the contents. The idea came from a can of white wood ear fungus that co-founders Ron and Mark Hanson saw in a Taichung supermarket two decades ago.

The intentional ambiguity creates confusion, stimulates curiosity and avoids attracting a singular type of audience, Ron Hanson tells the Taipei Times. The title has been called “revolting” in one article (that otherwise praised it), and it was once misplaced in the hallucinogenic section of a Canadian chain store.

“It’s an example of how translation can really alter the meaning of something; in Chinese it’s very innocent sounding but the English is jarring,” Hanson says. “We’re interested in this sort of in-betweenness; as New Zealanders living in Taiwan … we’re interested in exploring these sorts of gray areas when you’re communicating across cultures.”

Photo courtesy of White Fungus

But even the Taichung-based Hanson wondered how long he and his brother Mark could keep defying “conventional logic of what you’re supposed to do with a magazine.”

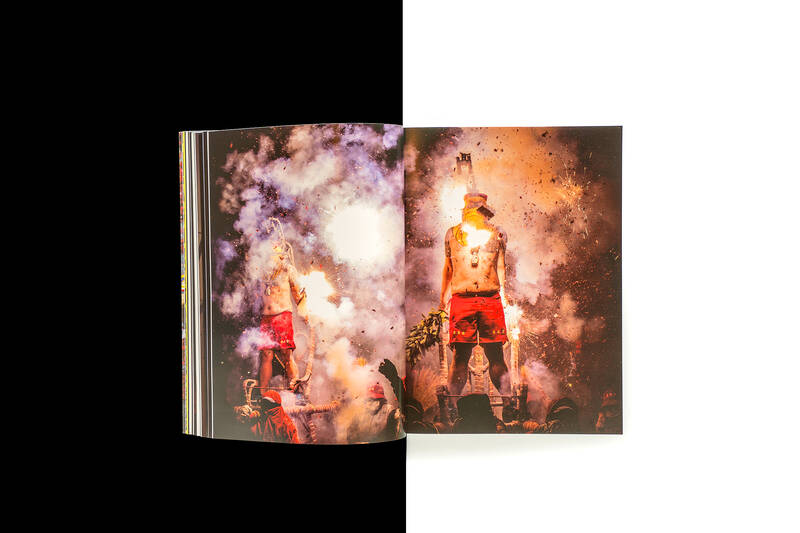

So far, 19 years. After a four-year pandemic hiatus, the 17th issue will hit the shelves outside Taiwan next week with a feature on the impact of climate change on Australia’s bats, poetry by Paul Celan, the avant garde jazz group The Art Ensemble of Chicago and a 8,000-word feature on the Bombing of Master Handan (炸寒單) religious ritual, where firecrackers are thrown at topless men paraded on a sedan.

The magazine used to be known for its popular launch parties and other art events, but Hanson says he’s simply getting a bit too old for that.

Photo courtesy of White Fungus

Hanson is especially proud of the Handan article, which took about a year to just research, calling it one of his all-time favorites.

“We’ve had Taiwan content in every issue since #7, but this is probably the deepest engagement we’ve had with Taiwan,” he says.

TWO SIDES OF FOLK RELIGION

Photo courtesy of White Fungus

Hanson and his small team began working on the latest issue in 2020, but COVID-19 put a halt to their plans.

“It’s difficult enough putting out a print publication during the best of times,” he says.

The Handan article was planned to be a short piece about the fascinating yet violent festival, but it mushroomed as the Hansons dug deeper.

Photo courtesy of White Fungus

“The more we looked into it the more interesting it became,” Hanson says. “Not just the connections to Chinese mythology, but the way some of these tales had morphed into something new under local conditions here. The connection with the criminal underworld is always interesting, and how that connects to tourism and politics — it’s a very unusual intersection which we tried to understand as best as we could.”

After about a year of research, they were able to meet some of the people who got “bombed” as representatives of the Handan deity, knowing enough by then to have some substantial conversations about what the ritual meant to them.

“It’s a brotherhood, it’s community, it’s a platform for them to express themselves, but it’s also dangerous and there’s a lot of bodily harm. It’s a complex phenomenon,” Hanson says. “It’s really a mixture of feelings when you see it; it’s loud, abrasive and violent but also beautiful. My personal experience was a very mixed sea of emotions.”

Immediately following the Handan article is a series of contemplative black and white photos of large-scale Taiwan’s deity statues by artist Yao Jui-chung (姚瑞中).

“We were interested in that juxtaposition because Handan is bright, spectacular and violent, while these photos show a calm, more meditative side … We don’t want the reader pigeonholing the phenomena of Taiwanese folk religion,” Hanson says. “It’s a bath for the eyes after all the intense stimulation.”

Hanson refers to Yao as his guiren (貴人, benefactor or life-changer). They first became friends at the Islanded art exhibition in New Zealand in 2006, and since the brothers had lived in Taiwan prior to that, Yao encouraged them to move back when the magazine began struggling.

“He took us all over Taipei and introduced us to all these artists and curators and just sped the whole process up,” Hanson says.

ORGANIC PROCESS

Putting the magazine together is usually an organic process; an artistic creation that doesn’t follow a fixed format or publishing date, Hanson says.

“It’s about what material we have access to at a given moment … The topics may be different but we look for threads that connect the material,” he says. “We want an audience that’s not just interested in one kind of material, we’re interested in the mixes, the surprises, the juxtapositions.”

In the latest issue, for example, fire is featured in three articles — besides Handan, the bat article discusses how they’re impacted by the 2019-2020 Australian wildfires, and a piece on composer Annea Lockwood’s London years mentions her “Burning Piano” performances in the late 1960s.

Hanson says they’ve thought of calling it quits many times in the past. In 2010, he was burnt out both mentally and financially and suffering from health issues after the 11th issue, and decided to make the 12th the last.

“We thought we’d do a final issue and make it exactly the issue we want to make, no advertising, no pleasing anyone,” he says. “But it suddenly really took off.”

That issue was selected for Museum of Modern Art in New York’s Millennial Magazines exhibition, leading to much major coverage and opportunities — they were in 17 exhibitions and fairs in 2012 alone, did a magazine residency in San Francisco and were offered a global distribution deal.

That issue contained their first interview with performance artist Carolee Schneemann, who was again featured in a 54-page interview in Issue 16, shortly before her death. That piece is another one of Hanson’s favorites as they were able to cover much ground with a famous artist and put out something meaningful as one of her final interviewers.

It all came full circle in 2014 when White Fungus was featured in a major Taiwanese publication. Turns out, the aunt of one of Mark’s students worked for the company that produced that original can of white fungus they saw in the supermarket that inspired the title and cover art.

“She turns up at school with a big box of these cans,” Hanson says.

These days, the world’s growing interest in Taiwan provides more fuel to carry on.

“We’ve been here for a long time and we were interested in it back when people were confusing Taiwan with Thailand, so we feel the compulsion to try and provide something a bit deeper, an alternative to the shallow media coverage that you see everywhere now,” he says.

The goal for now is to make it to 40 years.

“Avant garde is a really tough path that’s about longevity — if you stick around long enough you start to get some rewards. On a practical level, once we’ve come this far we might as well keep going,” Hanson says. “But there’s also a drive … that compels us to do things. We feel the need to fulfill our creative ambitions and we can’t just turn our back on it.”

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades