With summer approaching and the fireworks festival already underway, the time is right for a visit to the Penghu islands. If you’re also looking for somewhere away from the crowds and a more natural landscape, consider a visit to Dongji Island (東吉嶼) in Penghu’s extreme southeast. Only accessible by scheduled boat service from Taiwan since 2016, the island is still mostly wild and undeveloped, and will likely remain that way, as it is part of Taiwan’s newest national park, the South Penghu Marine National Park, established in 2014.

Stepping off the boat, your attention will first be drawn to the temple in the middle of the village, set at the far end of a long plaza. On the right is the village’s only store, a cramped room that stocks little more than instant noodles and canned drinks. Beyond the plaza, the village quickly turns into a collection of buildings in various stages of ruin, punctuated by the occasional well-maintained home belonging to one of the island’s 300 remaining residents.

Buildings here were traditionally made of locally gathered coral rocks, which were stacked to make walls, and then covered in a layer of cement. Though coral is no longer allowed in modern construction, there are plenty of examples of this classic Penghu architecture still standing in Dongji. There are several so-called “Western-style” mansions here, evidence of the island’s more prosperous past.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

Going left from the central plaza will take you to the harbor, past the scooter rental shop, to a beautiful white-sand beach. Even though it’s technically in the harbor, the water is still clear and turquoise, and it’s a fun, safe spot for children to play. Nearby is an intertidal zone that can be explored on your own at low tide after registering at the national park visitor center right behind the beach.

Before leaving the village on the north side, you will pass by the old elementary school and the police station. The school was officially declared closed when the last remaining local child graduated in 1992. Goats now enter one of the classrooms at their leisure, leaving the floor strewn with their feces. As a further sign of how long the place has been abandoned, a portrait of late president Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) still hangs on the far wall.

THE NORTH ROAD

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

The road to the north of the village can be explored by scooter for those with a time limit, but it’s only 2 km long so can easily be explored on foot. The first site is the Central Weather Bureau’s weather station, which is manned year-round. Behind the station the land reaches a high point at Bagua Mountain and drops vertically to the ocean and village below. This is where you can come to get a bird’s-eye view of the entire village, and practically the entire island, which is dwarfed by the vast blue ocean extended nearly unbroken in every direction.

Further up the road is the Dongji Island Lighthouse. It is currently closed due to renovations, but normally the grounds are open to the public during the daytime. Perched on the edge of a cliff over the Taiwan Strait, this structure has been guiding nearby ships for 85 years. Come visit at night for a ghostly sight: as the revolving light beam passes above Dongji Island itself, it briefly illuminates the rolling grassland that makes up the highlands of the island.

The lighthouse is not the only thing up here permanently watching over the Taiwan Strait. As you continue down the road through the deserted countryside, you may come across the occasional oblong arrangement of stacked coral rocks. This is the final resting place for one of the village’s former residents, now forever facing the waters from which they earned their living. These untended and often unmarked graves in the middle of an abandoned field are a physical reminder of the ephemeral nature not only of human life but also of a way of life for an entire community. Where once there were gardens tended by residents of a flourishing community, now there is only grass, goats and the crumbling ruins of walls, graves and a military fort.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

This fort lies at the end of the drivable road, on the east side of the island and was built during the Japanese era. The roofs are long gone, but the general layout of the camp is still obvious, including the air raid shelter. The shell of the observatory tower is still perfectly intact and the contrast of local black basalt and light-colored cement in its walls makes a visually attractive pattern.

OFF THE ROAD AND INTO THE WATER

The next stretch of coastline has no road at all, only a faint path worn into the grass by the local goat population, which far exceeds the human population. Along this shore, the volcanic origin of the Penghu islands is most apparent, as the vertical columns of basalt have eroded into seaside cliffs and unusual rock protrusions. This is the wildest part of the island, where you might not see another person anywhere, just grassy highlands, rocky shores and the expanse of the sea.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

Decades ago, it would not have been so, however, as the highlands were covered in individual vegetable garden patches called caizai (菜宅, literally “vegetable residence”), a common feature throughout Penghu. Due to the fierce winter winds, vegetables wouldn’t grow well unless sheltered, so coral rock walls were erected to offer some protection. Outside the village, the remainder of the island is almost entirely covered by these irregular rectangular divisions of rocks, now slowly being reclaimed by nature.

Continuing south, a more obvious footpath picks up again near a sandy beach. Far offshore here lies a thriving coral reef, accessible from shore to experienced snorkelers at high tide only. The safest and most convenient way to access this area is through a day trip package from Magong with the Venus tour group, as their boat takes you directly to the best part of the reef and ties off to a buoy, giving you direct, easy access. The area is known in Chinese as the “lavender forest,” as there are wide swaths of beautiful purple coral here that are unlike anything you’ll see elsewhere in Taiwan.

From the beach, the footpath around the south of the island and back to the village is not only obvious, but actively maintained every year by national park staff and volunteers. If you only have time for one excursion out of the village, it should be on this southern path, as it perfectly captures the raw beauty of Dongji: basalt cliffs, wild goats, turquoise waters and crumbling ruins, with the occasional fisherman still to be seen on the shores below.

Photo courtesy of Hsiao Wei-che

LOGISTICS

Dongji can be accessed by daily boat from Magong at 9:20am (NT$400). Thursday to Monday the Pescadores Ferry leaves Chiayi’s Budai Harbor at 8:20am for Magong, making a stop at Dongji (NT$1,020). Friday to Sunday and most Mondays and Wednesdays, there is also a ferry to and from Tainan’s Jiangjun Harbor. It leaves at 7:30am for Dongji (NT$1,500), and leaves Dongji around 4pm for the return trip. On some days, this boat also visits other islands in southern Penghu during the day.

For those looking to do water activities, a better alternative is to book through an operator like Venus (薇納斯海上娛樂), English available, LINE contact @697epglf, tel: (09) 8807-5092. Their package includes not only the transportation to and from Magong, but also the equipment, guide and boat service to the lavender forest snorkeling site, as well as stand-up paddleboard and see-through kayak use at the Dongji harbor beach. Lunch and scooter rental are also included.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

There are now several homes offering accommodations on the island. Dongji Homestay (東吉的家) is a good option as they can also provide meal service (breakfast, lunch and/or dinner) as requested (there are no restaurants on Dongji). The host is very hospitable, and can arrange snorkeling excursions either on Venus’s boat or from shore with a guide.

From the last quarter of 2001, research shows that real housing prices nearly tripled (before a 2012 law to enforce housing price registration, researchers tracked a few large real estate firms to estimate housing price behavior). Incomes have not kept pace, though this has not yet led to defaults. Instead, an increasing chunk of household income goes to mortgage payments. This suggests that even if incomes grow, the mortgage squeeze will still make voters feel like their paychecks won’t stretch to cover expenses. The housing price rises in the last two decades are now driving higher rents. The rental market

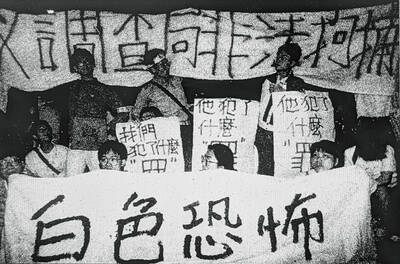

July 21 to July 27 If the “Taiwan Independence Association” (TIA) incident had happened four years earlier, it probably wouldn’t have caused much of an uproar. But the arrest of four young suspected independence activists in the early hours of May 9, 1991, sparked outrage, with many denouncing it as a return to the White Terror — a time when anyone could be detained for suspected seditious activity. Not only had martial law been lifted in 1987, just days earlier on May 1, the government had abolished the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of National Mobilization for Suppression of the Communist

When life gives you trees, make paper. That was one of the first thoughts to cross my mind as I explored what’s now called Chung Hsing Cultural and Creative Park (中興文化創意園區, CHCCP) in Yilan County’s Wujie Township (五結). Northeast Taiwan boasts an abundance of forest resources. Yilan County is home to both Taipingshan National Forest Recreation Area (太平山國家森林遊樂區) — by far the largest reserve of its kind in the country — and Makauy Ecological Park (馬告生態園區, see “Towering trees and a tranquil lake” in the May 13, 2022 edition of this newspaper). So it was inevitable that industrial-scale paper making would

Hualien lawmaker Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) is the prime target of the recall campaigns. They want to bring him and everything he represents crashing down. This is an existential test for Fu and a critical symbolic test for the campaigners. It is also a crucial test for both the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a personal one for party Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫). Why is Fu such a lightning rod? LOCAL LORD At the dawn of the 2020s, Fu, running as an independent candidate, beat incumbent Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmaker Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) and a KMT candidate to return to the legislature representing