Gerrit W. Gong, an Asianist who held many positions in universities and the US government, once said that “The Cold War’s thaw brought not an end of history, but its resurgence.” What Gong forgot to add was that resurgent history was in no small part expansionist fantasy.

During the 1930s, it was well established in Chinese minds that Taiwan lay outside of China. The thinking behind Mao’s famous comment that the Koreans deserved help breaking the chains of Japanese imperialism, as did the Taiwanese, was widely echoed across both Communist and Nationalist elites and was transmitted by them to the young.

Today we know terms like “united front” in the context of Chinese imperialism and expansionism, but in the 1930s the term had another meaning: it encapsulated the desire of Asians struggling to form a “united front” against external imperialism. Lan Shi-chi (藍適齊) identifies several publications aimed at Chinese youth in the 1930s that forwarded this concept (“The Ambivalence Of National Imagination: Defining ‘The Taiwanese’ In China, 1931-1941,” The China Journal, No. 64, July 2010).

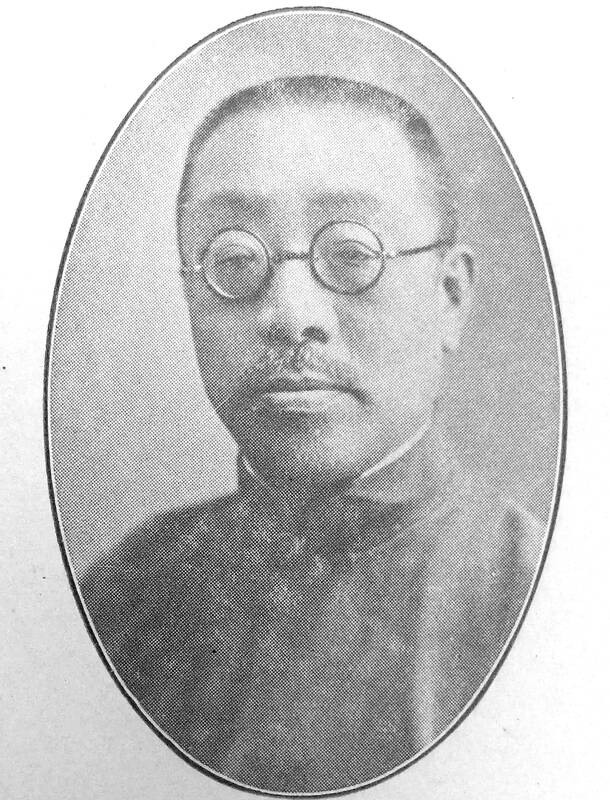

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

For example, Lan observes, a book aimed at young people entitled The Issue of Weak and Small Nations of the World had 14 chapters describing different nations, including Taiwan. Lan quotes the text as saying that Chinese may have forgotten the day they lost their nation, “but the Taiwanese will never forget (it) unless (their) nation is liberated (and) their independent autonomy movement succeeds.”

Another book series Lan instances discusses national liberation movements around the world. It locates Taiwan among its examples of national liberation movements in Asia, and says of Taiwan’s activities against Japanese rule since 1895 that: “… these national liberation struggles were all pointing their spears against Japanese imperialism and fighting for Taiwan’s independence and freedom.”

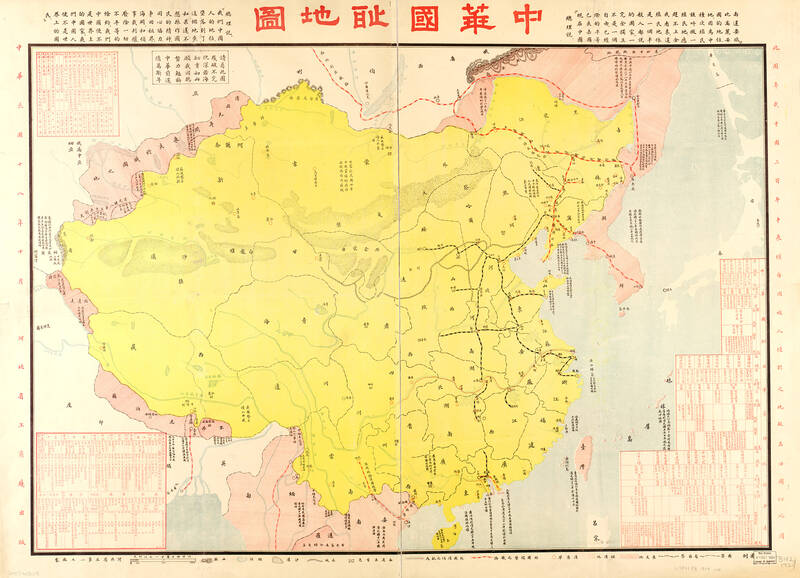

MAPS OF HUMILIATION

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

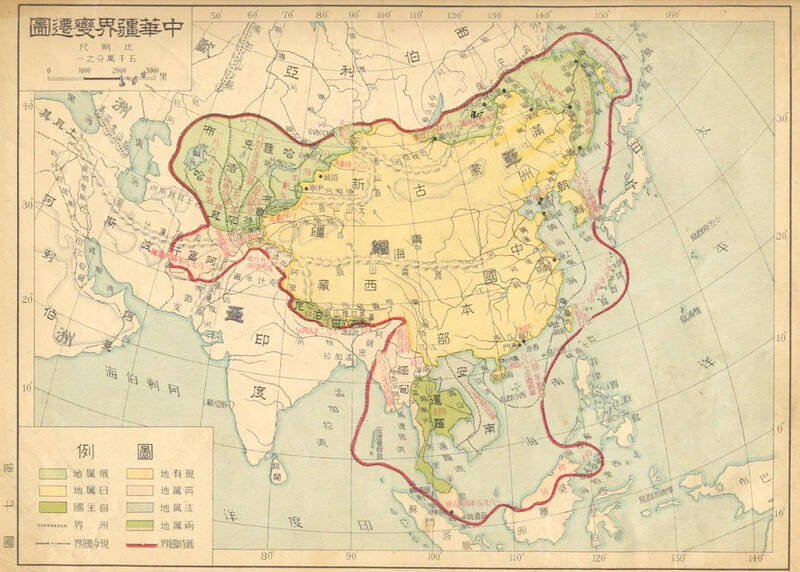

At the same time as elites were following a long tradition of mentally locating Taiwan outside China, a burgeoning private movement to get elites to see China’s borders as both expanding and expansive was occurring. According to scholar and research Bill Hayton, cartographer Bai Mei-chu (白眉初) began developing the existing idea of “maps of national humiliation” (國恥地圖), which purported to show territories “lost” to China.

These maps represent expansionist fantasies in cartographic form. Depending on the mapper, they might show that all of Siberia, or Malaysia, or Thailand and many other places in Asia are territories that China once owned, but have now been lost. Simply searching the text string in Chinese above will turn up many examples of them, including some apparently used in classrooms in the late 1930s.

These maps showed a Chinese world that resembles, in many ways, the expansionist ideology contained in the phrase “Russkiy mir,” familiar since the Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine.

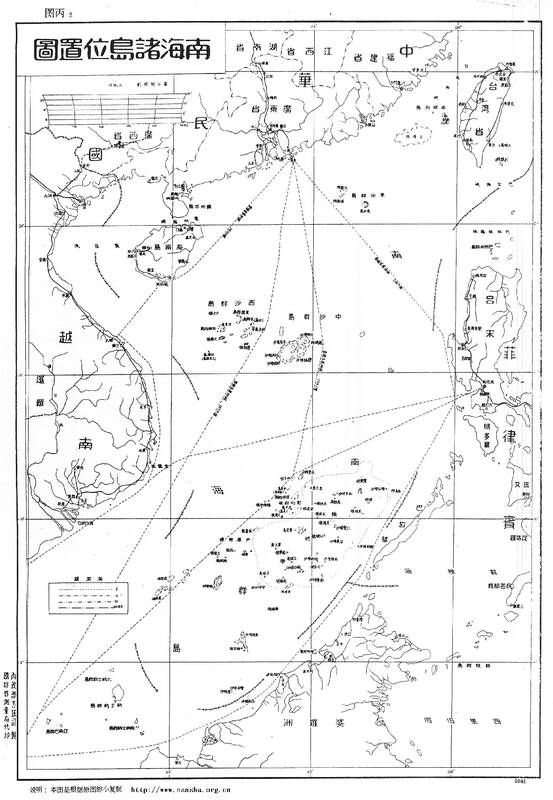

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Bai drew a line around the South China Sea and declared that it was lost territory. It was completely unknown to the Manchus, whose imperial borders ended at Hainan Island until 1900. As Hayton notes, in 1909 the governor of Guangdong Province sent a boat out to the Paracel Islands (Xisha Islands, 西沙群島) but because no Chinese pilot knew the area, they had to borrow German captains from a local trading firm. The islands finally appeared on Manchu maps that same year.

The first Republic of China (ROC) map was issued in 1912. It showed not only Taiwan but also northern Vietnam and Korea as “lost territories” awaiting return, and its borders were not defined. In fact, the term “renegade province” was originally used largely in southern China to refer to north Vietnam. It was applied to Taiwan later, and by outsiders first.

As Lan notes, it was Korea, not Taiwan, that was “usually represented as more significant to the Chinese and China as a nation than were the Taiwanese.” He examples the patriotic song “Ten Great Hatreds,” (十大恨) which said that the worst pain inflicted by the Treaty of Shimonoseki was the war indemnity paid to Japan, followed by the independence of Korea. Only then did Taiwan appear.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

INFAMOUS LINE

In the 1930s, even as Chinese elites were making comments about Taiwan’s independence and separateness from China that later Taiwan independence supporters would seize on, another strain of imagining was taking hold of China. Bai’s lines were taken up by other commentators, and eventually, the state. Late in 1946 the ROC would issue the first of the infamous 11-dash line maps showing that the South China Sea belonged to China.

Chinese interest in the South China Sea was stimulated by France’s move to grab the islands there as part of French Indochina. The ROC, which had no idea of the islands’ existence, sent for maps from Manila. Hence, the early ROC maps simply use the English names for the islands since there were no official Chinese names. ROC cartographers were so clueless that subsurface features, such as James Shoal, were reimagined as islands.

This second strain of expansionist imaginings was largely a private sector initiative picked up by the government in the late 1930s. It was inherent in the decisions made late in the 19th century to inflate the next Han-led state out to the borders of the Manchu empire and redefine all the neighboring peoples as “Chinese.”

Prior to 1942, as Alan Wachman observed in Why Taiwan? Geostrategic Rationales for China’s Territorial Integrity, both the Nationalist and Communist leaderships were indifferent to Taiwan during the interwar period. This changed only after the US entered the war and Chinese elites began to imagine what they could grab after the war, including Taiwan.

Many centuries of Chinese thinkers somehow missing that Taiwan was a core Chinese interest thus came to a sudden end.

FALSIFYING HISTORY

This desire to annex Taiwan led to the deliberate falsification of history later in the war by the Nationalists to construct an argument for incorporating Taiwan as a Chinese holding, as Steven Phillips has chronicled in Between Assimilation and Independence: The Taiwanese Encounter Nationalist China, 1945-1950. The discourse that recast annexation as “return” would be taken up by the People’s Republic of China when it came into power, and further developed with new absurd claims, such as the idea that the Yizhou (夷洲) chronicled in a third century text was Taiwan.

The arbitrary nature of Chinese claims is also highlighted by the status of Mongolia. Lan points to Chinese government survey reports on Taiwan and Mongolia. The Mongolians, despite acknowledged differences in language and appearance, are nevertheless presented as Chinese. The Taiwanese, who could have been criticized for learning Japanese language and culture, were admiringly presented as foreigners who were benefiting from Japan’s modernizing hand, Lan observes.

The discourse of the Japanese as evil colonialists despoiling a Chinese province, causing its people to adopt independence thinking, is entirely a postwar invention.

This is the ultimate and tragic contingency of Taiwan’s history: Taiwan could have gone the way of Vietnam and Korea and been recognized by the ROC as an independent state. Japan’s imperial dreams died at Midway and Guadalcanal, and with them, the prospect of Chinese acceptance of an independent Taiwan.

Notes from Central Taiwan is a column written by long-term resident Michael Turton, who provides incisive commentary informed by three decades of living in and writing about his adoptive country. The views expressed here are his own.

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

For many centuries from the medieval to the early modern era, the island port of Hirado on the northwestern tip of Kyushu in Japan was the epicenter of piracy in East Asia. From bases in Hirado the notorious wokou (倭寇) terrorized Korea and China. They raided coastal towns, carrying off people into slavery and looting everything from grain to porcelain to bells in Buddhist temples. Kyushu itself operated a thriving trade with China in sulfur, a necessary ingredient of the gunpowder that powered militaries from Europe to Japan. Over time Hirado developed into a full service stop for pirates. Booty could

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them

Politically charged thriller One Battle After Another won six prizes, including best picture, at the British Academy Film Awards on Sunday, building momentum ahead of Hollywood’s Academy Awards next month. Blues-steeped vampire epic Sinners and gothic horror story Frankenstein won three awards each, while Shakespearean family tragedy Hamnet won two including best British film. One Battle After Another, Paul Thomas Anderson’s explosive film about a group of revolutionaries in chaotic conflict with the state, won awards for directing, adapted screenplay, cinematography and editing, as well as for Sean Penn’s supporting performance as an obsessed military officer. “This is very overwhelming and wonderful,” Anderson